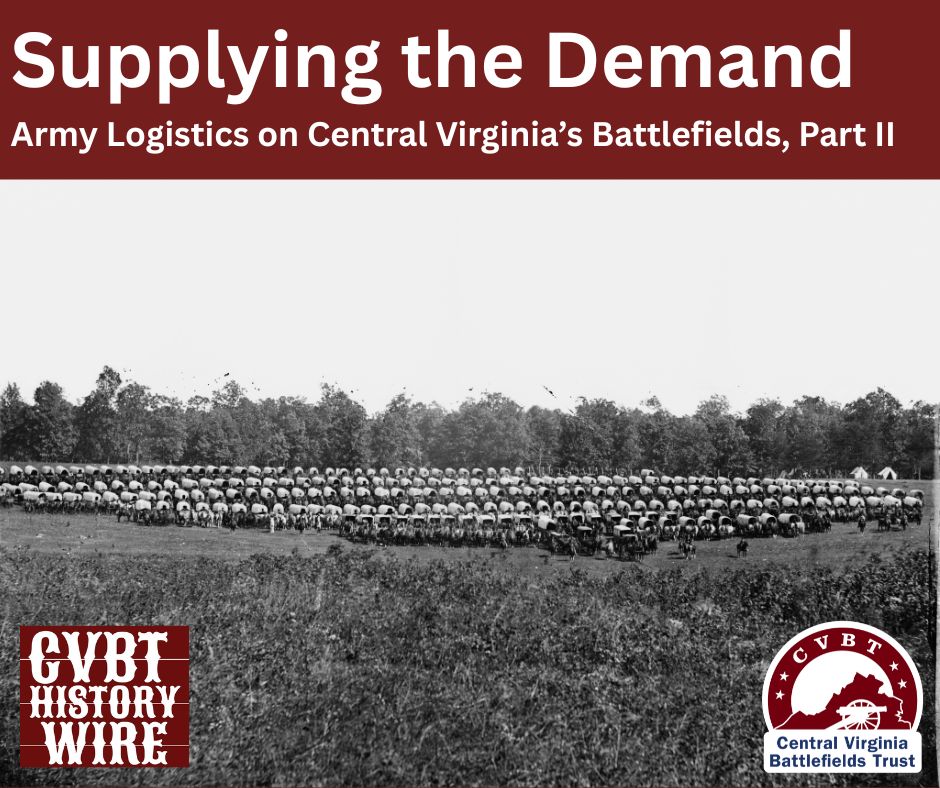

This Timothy O’Sullivan photograph shows about 250 of the Army of the Potomac’s enormous fleet of over 5,000 wagons and ambulances that went into the Overland Campaign.

(Library of Congress)

Introduction

Civil War armies primarily did three things: they marched, they fought, and they camped. All three of these things required supplies (some more than others) in various ways. Whether an army was on campaign or in camp, it still had to be fed and sheltered. Militarily, replacing damaged or worn out equipment was almost as much of a concern as recruiting new soldiers to fill the ranks of the fallen. An army’s existence and efficacy depended on logistical support.

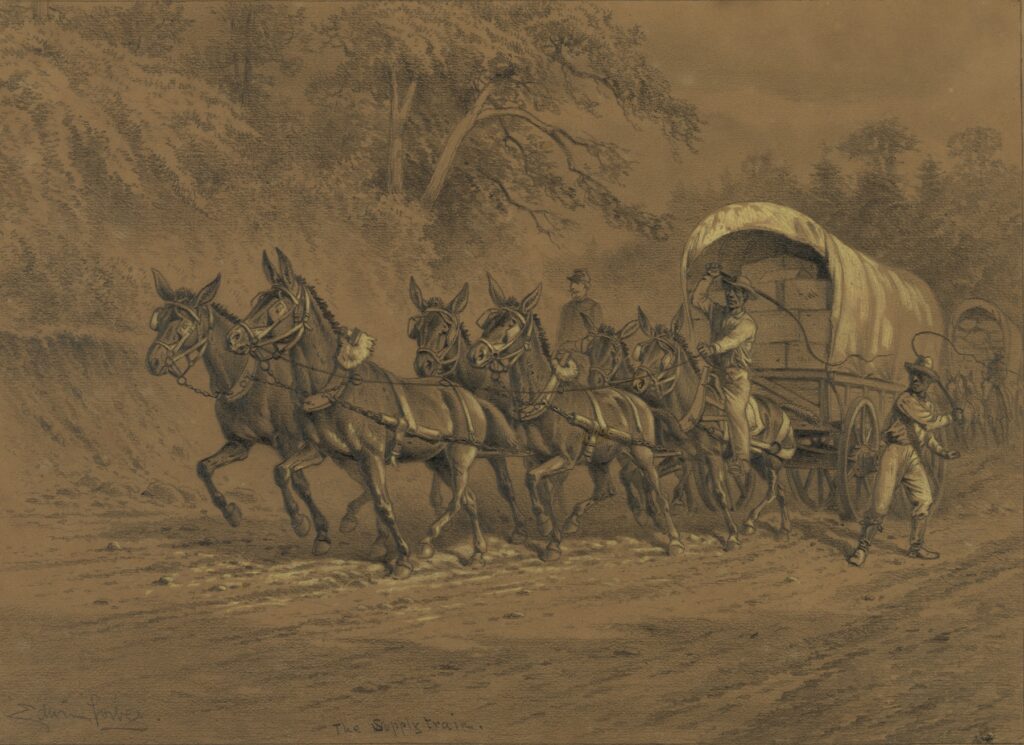

In Part I, we saw the significant role that innovative forms of transportation played in army logistics. Ocean-traveling steamships, river-plying steamboats, and terrestrial-bound railroads all moved military materiel from centers of production to wharves, depots, warehouses, and then to field armies. However, when armies broke away from lines of communication supported by steam-powered means, they relied heavily on the age-old and unsung supply wagon and the animals that pulled it. However, wagons, like other modes of transportation, presented some challenges.

A team of six horses or mules and a wagon took up about the same road space as a modern motorcoach bus.

(Library of Congress)

The basic Civil War supply wagon could carry just over a ton of freight. A six-horse or mule team could carry about 1000 more pounds than a team of four animals. As one might imagine, these teams and conveyances took up a tremendous amount of road space. As a modern comparison, a six-mule team and army wagon, from the nose of the lead mule pair to the trough tailgate at the rear, covered about the same distance as one of today’s motorcoach buses.

“In every war in every age, the forgotten weapon is food . . . For to kill, soldiers must live . . . to live, they must eat.” So says the opening line to Alvarez Kelly, the 1966 motion picture starring William Holden and Richard Widmark, and quite a true statement. Soldiers had to eat to perform well and receive fairly regular rations to help maintain their morale. The same largely applied to army animals. Civil War army wagons transported food for both man and beast.

Ration regulations stipulated that soldiers were supposed to get about three pounds of food per day. For a 14,000-man corps, that added up to about 42,000 pounds of food per day. That haul would require approximately 21 wagons alone.

The armies’ need to also transport animal feed was briefly mentioned in Part I. But putting some math to that statement helps add emphasis and shows the armies’ wagon demands. Horses and mules were supposed to get about 25 pounds of food per day. So, a single team of six horses or mules requires 150 pounds per day. If a team was to travel on a 120-mile round trip over a 12-day period, each wagon needed to carry 1,800 pounds of food just for the animals pulling the wagon. As stated above, a team could carry about a ton, so some wagon teams were solely carrying food for the animals.

Ammunition was also a weighty matter. One box of standard rifle ammunition contained 1000 cartridges and weighed about 100 pounds. Each soldier carried 40-60 cartridges on their person: 40 in his cartridge box and usually 20 in his pockets or knapsack. If a 500-man regiment shot 50 rounds each in a fight, they would expend 25,000 rounds. 25,000 rounds would require 25 100-pound boxes weighing in total 2,500 pounds. Basically, one wagon would be needed to carry that single regiment’s ammunition for that one engagement.

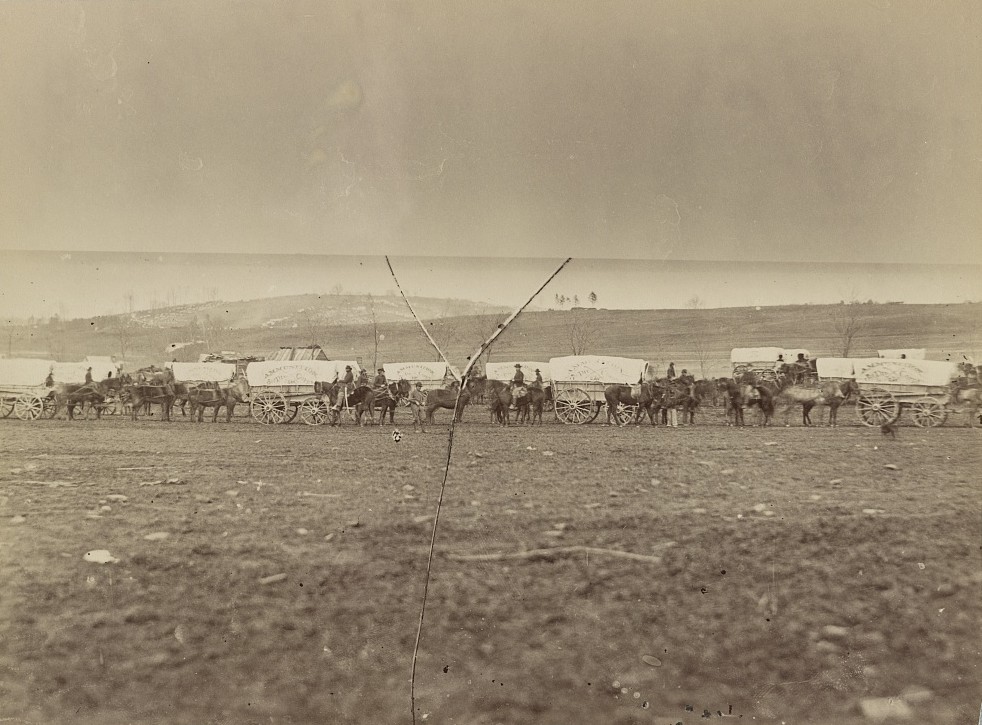

Made near Brady Station, this photograph shows covered wagons painted with “Ammuniton 3rd Division Cavarly Corps,” and crossed sabers.

(Library of Congress)

Wagon travel was slow. A fully loaded wagon could make about 2.5 miles per hour over good roads. Stalls and backups were frequent, especially on bad roads. Muddy routes were virtually impossible to navigate carrying just about any weight of freight. Most wagons did not come with driver’s seats, rather, the driver rode the left wheel mule, which was the one closest to the wagon. The sets of mules were called the wheel pair, which were usually larger and stronger animals; the swing pair, which were in the middle; and the lead pair, as the name implies, at the front of the team.

Most wagons came equipped with a toolbox on the front for repairs, a feed trough on the back, and an iron bucket that held grease and swayed from the rear axle. Canvas covers supported by wooden bows were common to protect the freight from the elements.

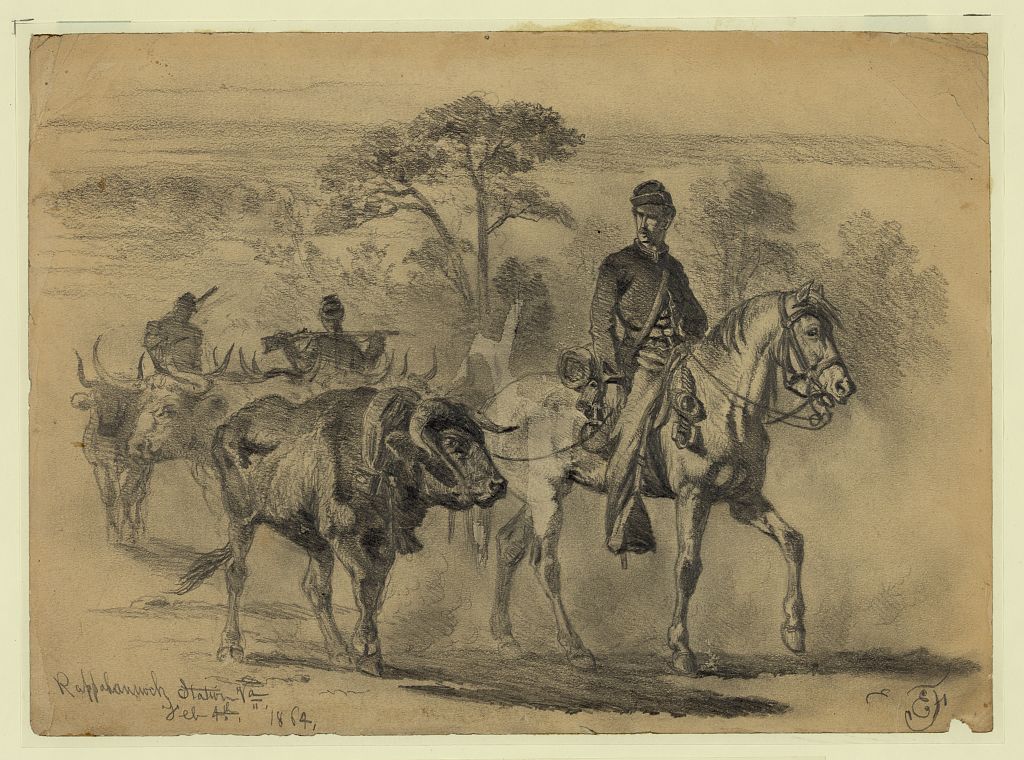

Helping reduce the need for so many wagons while at the same time supplementing the army’s monotonous boxed bread and barreled pork rations, herds of cattle joined the army’s movements to provide fresh “beef on the hoof.” About 500 one-day meat rations could be derived from a single animal. Eight cattle could provide 4,000 rations, and 24 beeves could feed a corps of 12,000 men for a day.

Enormous herds of cattle traveled with the armies supplying rations of fresh beef.

Sketched by Edwin Forbes

(Library of Congress)

These examples of commissary and ordnance transportation demands help us better understand some of the means and circumstances under which those in the army’s logistical roles labored under.

The Mine Run Campaign

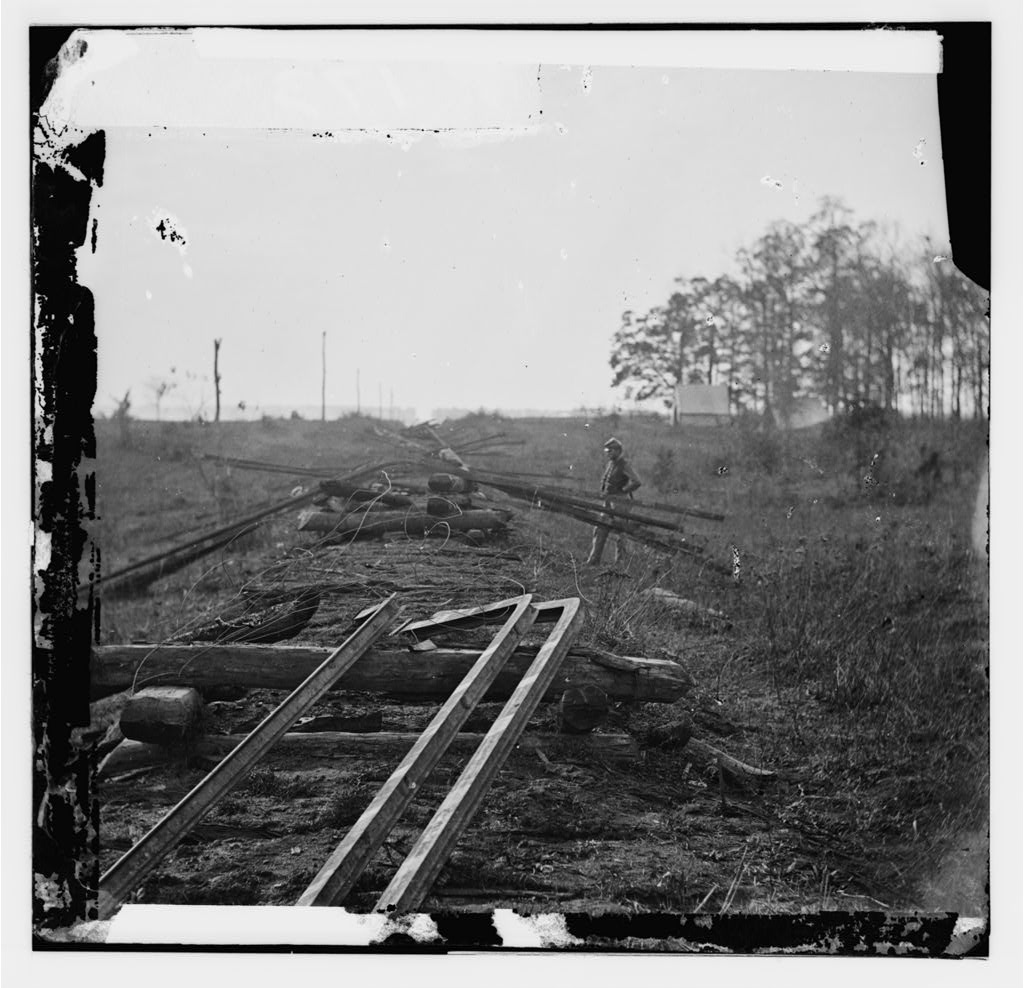

Made in the fall of 1863, this photograph shows the amount of damage inflicted on the O&A by Confederates. Note the tangles of telegraph wire.

(Library of Congress)

After the Army of the Potomac and Army of Northern Virginia briefly moved the war into Pennsylvania during the summer of 1863, they returned to the Old Dominion and set up camps in Culpeper County and Orange County respectively.

August and September 1863 saw the XI and XII Corps depart for Tennessee, reducing the Army of the Potomac by about 20,000 soldiers. A Confederate advance in October along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad (O&A RR), which served as Meade’s primary route of resupply, prompted his recently reduced army to fall back to Centreville. Understanding the vital importance of the O&A RR to Meade’s efforts to move along that route of invasion, Lee’s men tore up significant sections of track during their subsequent withdrawal to Brandy Station.

Work on the railroad line progressed quickly and by early November Meade’s men attacked at Kelly’s Ford and Brandy Station pushing the Confederates across the Rappahannock River and setting up camps there, extending the rail repairs to nearby Culpeper.

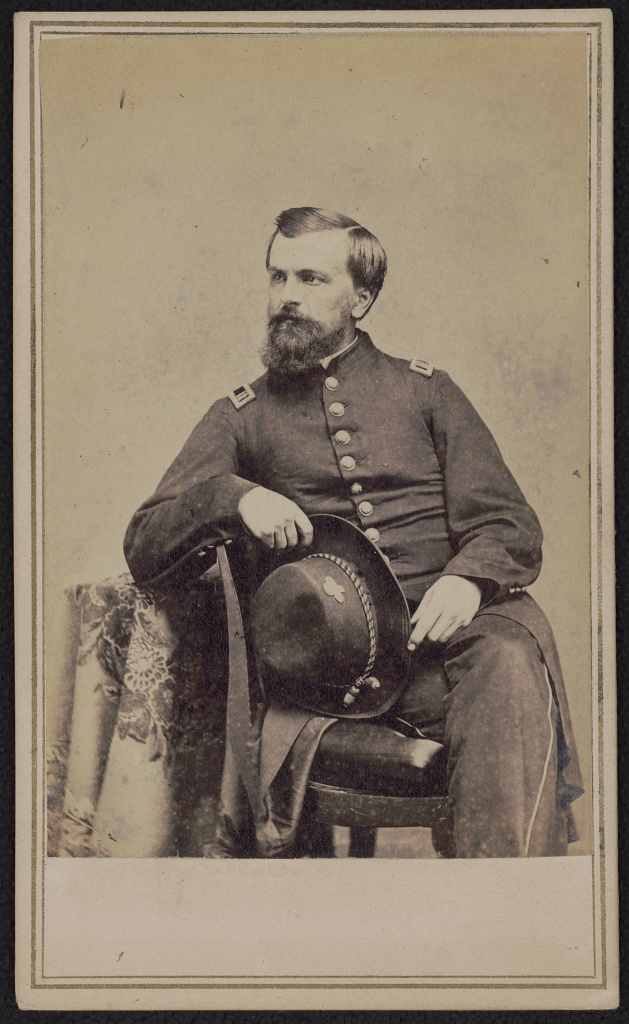

Fiske corresponded frequently with the Springfield, Massachusetts Republican newspaper under the pseudonym “Dunn Browne.”

(Libray of Congress)

In a letter to Gen. Meade on November 18, 1863, the Army of the Potomac’s quartermaster, Brig. Gen. Rufus Ingalls, stated, “experience has shown that there is no military advantage in loading the men heavily. They become quickly fatigued and waste the rations. In case of battle they abandon them. If eight days’ are carried, hardly more than five can be calculated upon.”

On the eve of the Mine Run Campaign, the 14th Connecticut’s Capt. Samuel Fiske wrote his usual column to the Springfield Republican newspaper in Massachusetts. In it, Fiske was pleased to hear about a new order “that the men are not to be compelled to carry on their backs henceforth more than five days’ rations at one time.” Previous practices of carrying “eight days’, then ten days’, and, in one or two instances, the eleven days’ mule burden piled on the men’s backs, over and over again, cruelly, wastefully and uselessly, never once accomplishing the purpose, never in a single lasting over six days. . . .,” aggravated Fiske. He claimed the same went for ammunition. He thought a soldier should only carry what his cartridge box holds. “Why, more cartridges have been wasted during this war by compelling the men to carry sixty, eighty and even a hundred rounds. . . .,” Fiske grumbled. By reducing the burden the men would benefit in several ways, including not being “blowed up by a match setting fire to an extra package in their breeches pocket.” In addition, he believed it would save the government money by reducing the false demand caused by waste.

Numerous Army of the Potomac soldiers mentioned food shortages during the Mine Run Campaign, particularly in its final last days. On the way back to their Culpeper County winter camps, New York artillerist George Perkins wrote, “Rations getting short. Nothing but a little flour and some boiled beef which furnished just one meal and which was all we had this day.” Corp. Thomas Mann, 18th Massachusetts Infantry, wrote about December 1: “our rations had now given out and I had been 26 hours without a morsel of bread.” Mann added, “From Thursday [December 1] noon I eat nothing until 12 o’clock at night when our rations came up so that all I could get to eat for over 40 hours was 1/4th lb raw pork and 2 ½ hardtack. Likewise, Corp. Joseph Hodgkins, 19th Massachusetts Infantry, concurred with Perkins and Mann, writing in his diary about the slim rations at the end of the campaign. On December 2, Hodgkins wrote “Had but a little over four hardtack since yesterday.” Massachusetts artillery bugler Charles Wellington Reed, wrote to his mother soon after the campaign and in answering her question about how the mission went, he noted, “if I must speak the truth we did suffer both from the severity of the weather and scarcity of rations.” He elaborated by stating, “our rations were only coffee, hard tack, and pork scant at that[.] vegetables are altogether out of the question on a campaign, in fact we have had potatoes and onions but twice since we have been back.”

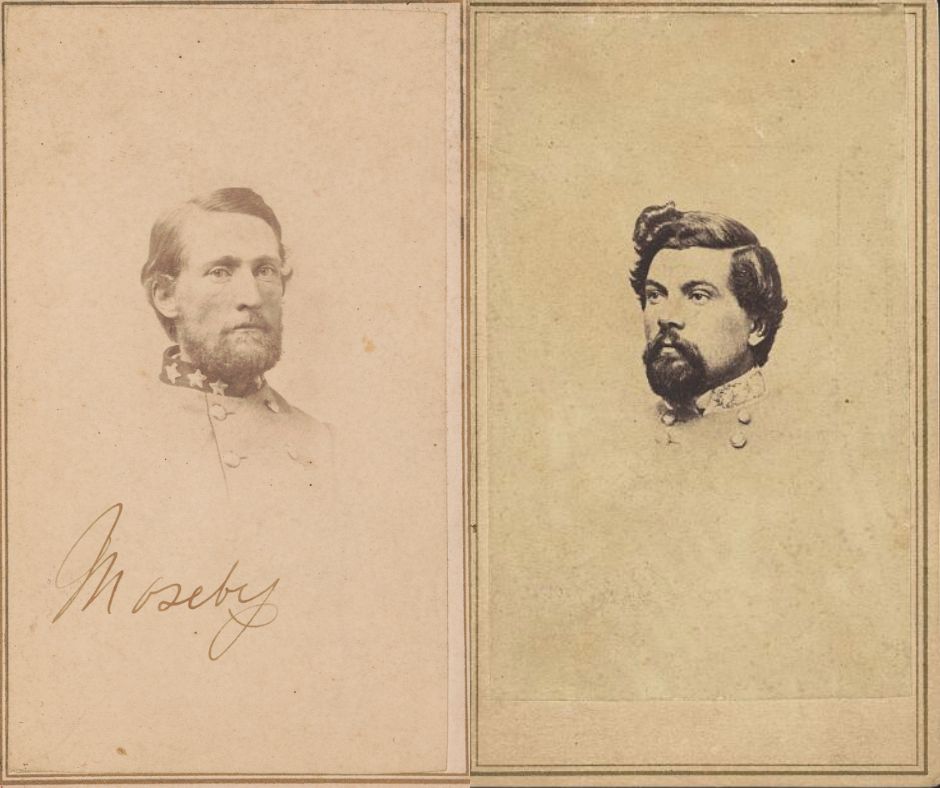

Cavarly foces under Mosby and Rosser led successful stikes against Union supply wagon trains during the Mine Run Campaign.

(Library of Congress)

Part of the Federal shortage could be attributed to Confederate cavalry strikes. On December 2, Gen. Robert E. Lee reported that on November 27, Brig. Gen. Thomas Rosser’s cavalry “attacked their train near Wilderness Tavern and burned a considerable number of wagons, bringing off 18, together with 280 mules and 150 prisoners.” Lee also noted that Maj. John Mosby “fell upon a train of wagons at Brandy Station and destroyed a number of them, bringing off 112 mules and a few prisoners.”

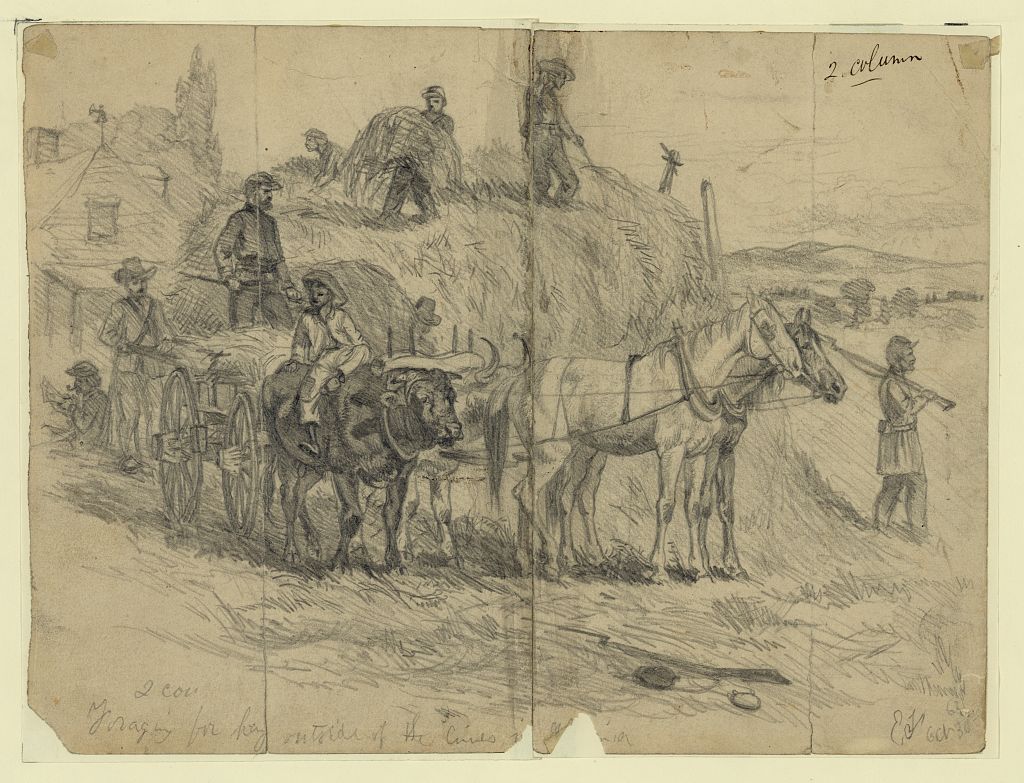

Sketch by Edwin Forbes

When supply lines broke down and grass was not available for equines to graze, details of foragers often went out and found and took what they needed.

(Library of Congress)

The Confederates were not without troubles of their own. Gen. Lee wrote President Davis on November 10 about his concerns of a movement by the Army of the Potomac. Lee promised to “bring [Meade’s army] to battle” but was worried about the ability to succeed. “The country through which we have to pass is barren. We have no forage on hand and very little prospect of getting any from Richmond. I fear our horses will die in great numbers, and, in fact, I do not know how they will survive two or three days’ march without food,” Lee worried. “I hope every effort will be made to send some up, and I think it would be well to stop the transportation of everything on the railroad excepting army supplies,” the general added.

The same day, Lee told Secretary of War James Seddon that the condition of the Virginia Central Railroad “seems to become worse every day.” Although Lee was not able to spare men to help with repairs, he hoped “something may be done to put it in good repair, so that it may be relied on for the regular transportation of our supplies.” Should that fail, Lee thought it would be necessary “to fall back nearer to Richmond.” Seddon responded on November 14 that he “instructed the Quartermaster-General to send forward whatever small supplies he could command” from Richmond “or any other convenient depots in the State.” Seddon hoped “supplies in the future will be more regular and abundant.”

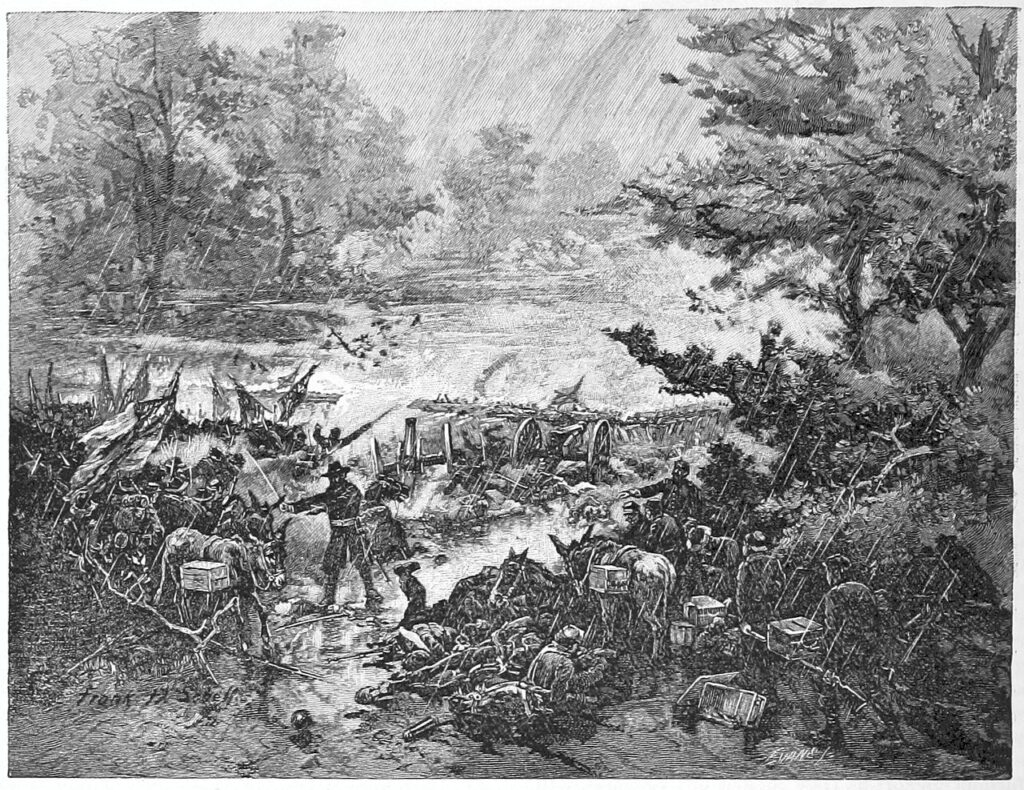

The Army of Northern Virginia’s stong postion along Mine Run thwarted the Army of the Potomac’s hopes for a successful late fall 1863 campaign.

(Harpers Weekly, January 2, 1864)

To help remedy the shortage situation, Commissary General Lucius Northrop suggested Lee implement the Impressment Act. Lee thought it would be undesirable to do so and would lead to a breakdown in discipline. Lee preferred to “endeavor to collect all the supplies for this army that I can legitimately . . . and keep it in the best condition I can. But unless it is supplied with food, it will be impossible for me to keep it together,” the commander warned. Shortages were compounded by the loss of hogs and beef from the Trans-Mississippi region due to Vicksburg’s earlier capitulation, as well as the evacuation of Tennessee in the summer and fall of 1863. In addition, a general failure of the Virginia wheat crops due to too much rain strained the ability of the Commissary Department to meet the needs of Lee’s army.

On November 11, 1863, Pvt. Walter Battle of the 4th North Carolina wrote home telling about receiving “a large supply of winter clothes of every kind” on November 7, and “the men were just trying them on” when they were surprised at Rappahannock Station. Pushed back across the Rappahannock River, Battle and others lost difficult to replace equipment. Battle “happened to take my shawl and oil cloth with me, which I saved,” however he “lost my two blankets, a pair of cotton drawers, and a pair of socks, which I had just drawn.” He also saved his overcoat, but lost his knapsack, tin plate, tin cup, and presumably his haversack. He asked his mother to send him some things by way of a comrade at home as replacements.

The campaign’s cold weather made the men feel the effects of supply shortages more keenly. Although he was spared many of the inconveniences of the army’s deficiencies, Maj. Walter Taylor of Lee’s staff wrote that the morning of November 27 “was intensely cold.” Taylor noted, “the ground was frozen hard as ice. It was so funny to notice the effects of the cold upon everyone’s beard—all around one’s mouth innumerable icicles hung . . . from moustache and whiskers. . . .” Most of the soldiers in need of proper protection probably did not find humor in the frigid temperatures. Only back on November 10, Lee had complained to Seddon that “many of our men in this army are still barefooted. . . .” and noted the “great importance to the comfort and health of the men that they should all be well shod and clothed in such weather as we may expect now for some months.”

Pvt. Battle wrote his mother again on December 3 giving some details about Mine Run. During the Federal withdrawal, Battle and his comrades captured a few stragglers. “They were the poorest Yankees I ever saw,” Battle noted. “They did not have one mouthful to eat and said they had not had any in four days,” he added. The captives claimed Confederate cavalry captured their supply wagons and some of them offered Battle $2.00 for a hardtack cracker. Battle wrote that “we were rationed up two days and I could eat everything in my haversack, so I could not spare them.” One Federal was able to finally convince Battle to trade him a hardtack cracker for the Yankee’s knapsack, which contained a new pair of shoes and a shelter tent that Battle prized.

The Wilderness

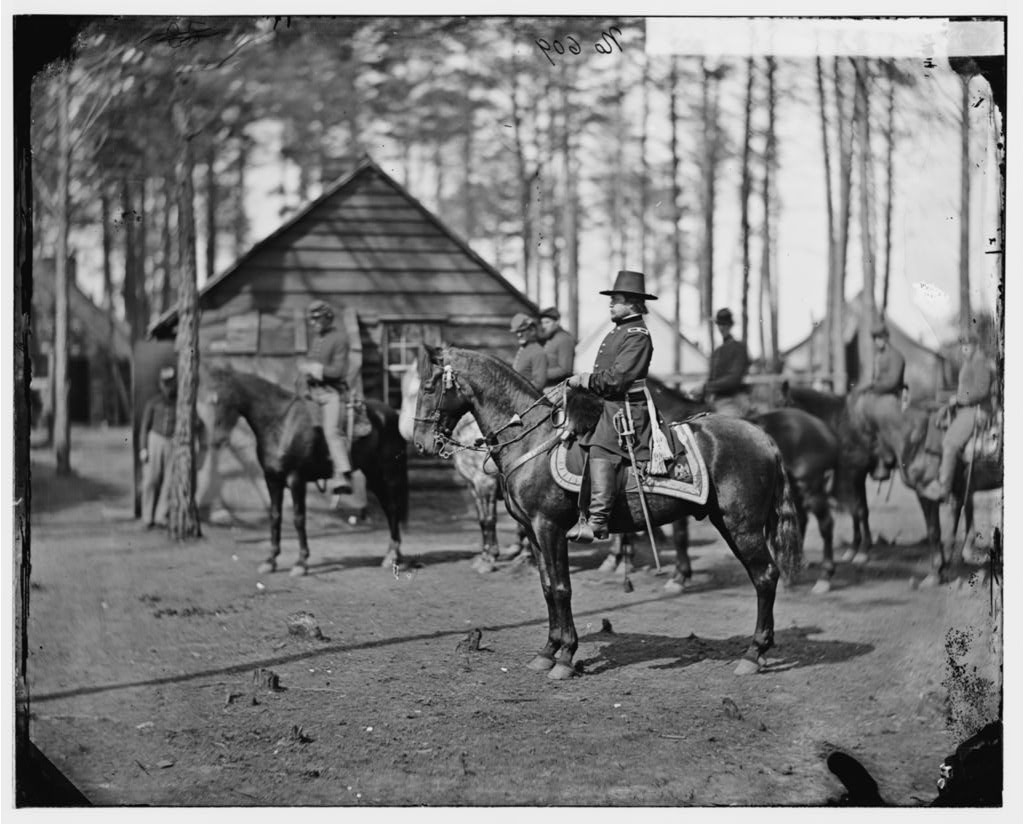

Ingalls boasted that “Probably no army on the earth ever before was in better condition in every respect than was the Army of the Potomac on the 4th of May, 1864.”

(Library of Congress)

After falling back to their camps in Culpeper County and reestablishing direct contact with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, supplies flowed in regularly for the Army of the Potomac. The army’s soldiers also had access to well-stocked sutlers and made requests for boxes from home that brought some variety to their monotonous diets as well as supplemental clothing and personal items. Writing his campaign report almost four months later, Chief Quartermaster Ingalls bragged, “Probably no army on the earth ever before was in better condition in every respect than was the Army of the Potomac on the 4th of May, 1864.”

Supplying an army of about 120,000 soldiers was no easy task, but to help, as Ingalls explained, “There were 4,300 wagons, 835 ambulances, 29,945 artillery, cavalry, ambulance, and team horses; 4,046 private horses; 22,528 mules; making an aggregate of 56,499 animals.” In addition to what the men were carrying to supply themselves with ammunition and three days of rations, “The supply trains were loaded with ten days’ forage (grain) and ten of subsistence.” Ingalls allowed half of the ammunition, intrenching tools, and ambulance wagons, a few light spring wagons and pack animals” to go with the army while the balance gathered at Richardsville to await needs. Also accompanying the army were large herds of cattle for fresh beef.

According to Ingalls’ report, on May 4 the army cut ties with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad north of the Rappahannock River and had all supplies sent to Alexandria. There they would wait until developments of the campaign determined where new depots needed to be established. Eventually the “flying depots” were set up at Aquia, Belle Plain, and Fredericksburg.

However, the army was not done with the railroad just yet. Initially the Union wounded from the Battle of the Wilderness were sent in ambulances and empty wagons to Rappahannock Station (just north of the river) for transport by rail to Washington-area hospitals. Soon however, transport of the wounded switched to Fredericksburg. Taken at first from Fredericksburg to Aquia by wagon—and by rail line once it was repaired—vessels took them on the Washington hospitals. After dropping off the wounded, the now empty wagons, “as a rule . . . returned laden with forage and subsistence” from the new supply depots to provision the troops.

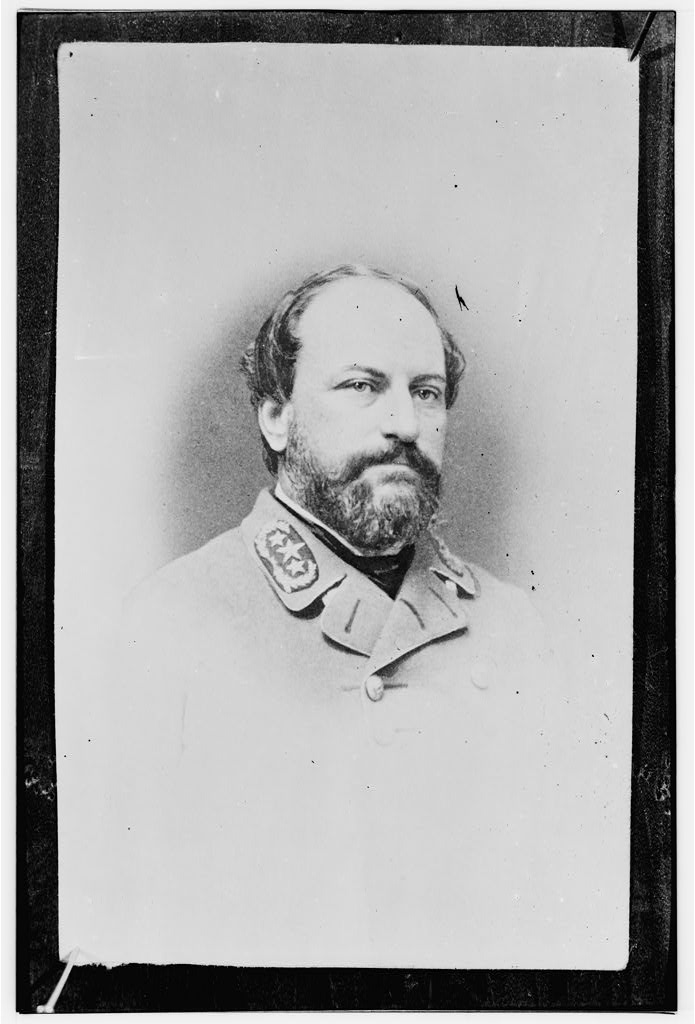

As Quartermaster General, Lawton had to explain to Gen. Lee that there were no blanket manufacturers in the Confederacy.

(Library of Congress)

Confederate supply deficiencies continued through the winter of 1863-64 while they wintered in Orange County. On January 10, 1864, Lee wrote to Quartermaster General Alexander R. Lawton, “The want of shoes and blankets in this army continues to cause much suffering and to impair its efficiency. In one regiment . . . there are only 50 men with serviceable shoes, and a brigade that recently went on picket was compelled to leave several hundred men in camp who were unable to bear the exposure of duty, being destitute of shoes and blankets.” Lee worried about bringing more men into the army when they were not able to properly equip those already there with basic necessities. About the blanket issue, Lawton responded, “we are entirely dependent upon the foreign markets for our supply. There is not a solitary establishment within the limits of the Confederacy where they are made, nor is there one . . . that possesses the appliances for making them.”

As far as food limitations, Commissary General Northrop again blamed the Confederacy’s inconsistent railroad conditions for the inefficiently in transporting foodstuff from points of production to the armies in the field. “Over 100,000 bushels of corn demand transportation; not over one-third of what is already on the road has arrived. Unless all passenger trains are stopped the consequences may be fatal. In addition, transportation for bacon is needed from Georgia,” Northrop noted.

A Federal cavalry raid in late February and early March led by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick and Col. Ulrich Dahlgren caused some damage to the Virginia Central Railroad, but it was quickly repaired and apparently did not cause much disruption in the already uneven supply flow.

Despite the consistent supply shortages, soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia were buoyed by a string of victories in smaller battles that occurred in the late winter and early spring of 1864. Successful fights at places like Olustee, Florida; Plymouth, North Carolina; and Fort Pillow, Tennessee, brought hopes of similar victories for the spring campaign in Virginia. Additionally, a string of revivals that coursed through Lee’s army helped take the soldiers’ minds off of governmental deficiencies by blending religion with patriotism and making calls for their continued sacrifices for the greater good. Yet, belt-tightening only went so far. Desertions still plagued the ranks. Much of the discontent was linked to the army’s supply-related privations. The 45th North Carolina’s Sgt. Christopher Hackett wrote home in late March 1864 that he received rations “regular enough but getting enough is the thing.” Hackett wanted out. “I intend to make the trip [home] the first opportunity the offers itself . . . for I intend to get out of this war in some way and there is but one way that one can make sure [his] escape.”

A week before the Battle of the Wilderness, Sgt. Marion Hill Fizpatrick, 45th Georgia, thanked his wife in a letter for the box she sent to supplement his army-issued rations. He enjoyed “biscuits for breakfast every morning and cornbread for supper or dinner.” She also apparently sent meat, as he also remarked, “My piece of meat is of great value. The meat we draw [for rations] is very inferior, and comes in small doses.”

Relatively close proximity to the Virginia Central Railroad and the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad helped maintain a respectable flow of supplies to depot points that wagons then carried to the parts of Lee’s army during the Battle of the Wilderness. Being able to hold their ground for the most part on May 5 and 6, 1864, also allowed the Army of Northern Virginia to maintain its communication lines.

The flow of supply is supported by the diary of Pvt. Henry Beck, who served detached from the 5th Alabama Infantry as a brigade commissary clerk. On May 4 and 5, Beck noted the supply wagon train moving up to the front and then back again to keep it safe. On May 7 he wrote, “Gave out rations & started to the front with the train. Staid about 1 ½ miles in rear of line of battle until late in the evening when we carried the train forward.”

Spotsylvania Court House

By Edwin Forbes

Everything from hard tack to ammunition to medical supplies had to be moved by wagon at one point or another. Note the teamster riding the left “wheel mule.”

(Library of Congress)

Transitioning from the fighting at the Wilderness to that of Spotsylvania required stretching the Army of the Potomac’s supply lines. Chief Quartermaster Ingalls reported, “from May 4 to 13, inclusive—our trains occupied the plank road from Chancellorsville via Alrich’s to Tabernacle Church, and to the south at Piney Branch Church and Alsop’s, changing parks according to movements of our troops or that of the enemy.” Guarding much of the supply wagon train were men from the Fourth Division of the Ninth Corps, United States Colored Troops under the command of Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero.

Logistics also involved moving the wounded. After suffering high casualties at the Wilderness, on May 8, the 57th New York received orders to accompany the wounded to Fredericksburg. Lt Cornelius Moore wrote his sister about the favored change in environment “miles away from the sounds of battle at the front . . . and resting from the fatigues of the past week.” In a follow up letter three days later, Lt. Moore described Fredericksburg as “one grand hospital,” and that “many [wounded] have been sent on to Washington, by way of Aquia Creek, or Belle Plains.” Additionally, Moore noted, “both male and female, of the U.S. Sanitary and Christian Commissions have arrived, brought on with them medical supplies, and are doing great things toward alleviating the suffering of the wounded in the city.” Moore also explained, “When we first came here it was impossible to obtain supplies either from the main Army, or from Washington, and the wounded . . . were actually suffering from hunger.” To help solve the problem Moore and his comrades searched Fredericksburg houses for “provisions as would do for the wounded.”

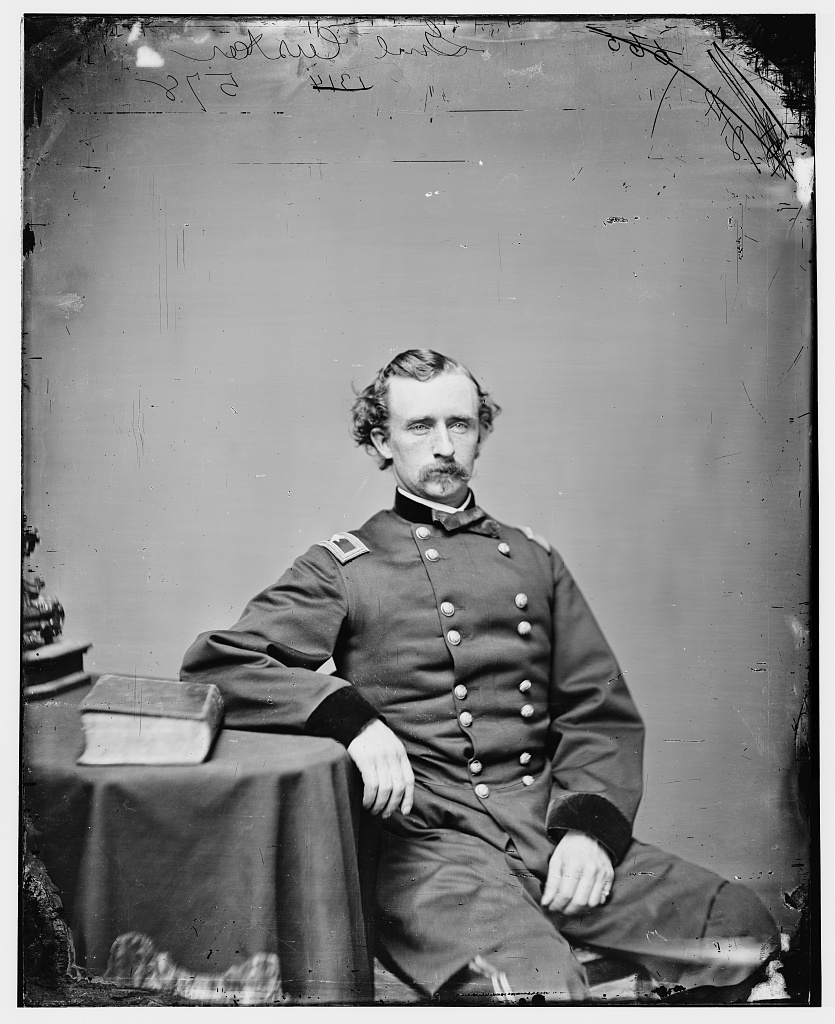

Custer’s cavalrymen captured or destroyed an estimated 1.5 million Confederate rations during their May 9, 1864, raid on Beaver Dam Station.

(Library of Congress)

In another effort to damage the enemy’s ability to supply itself, and just a day into the fighting at Spotsylvania, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan received permission from Gen. Grant to break away from the Army of the Potomac’s main force and lead a cavalry raid toward Richmond. Along the route he ordered Brig. Gen. George Custer to Beaver Dam Station on the Central Virginia Railroad. Arriving on the evening of May 9, the cavalrymen found Federal prisoners captured during the Battle of the Wilderness and in the opening fight at Spotsylvania, who they freed. Custer and his men also captured “three trains and two first-class locomotives. The trains were heavily laden with supplies for the [Confederate] army,” Custer reported. He continued, “In addition, we captured an immense amount of army supplies, consisting of bacon, flour, meal, sugar, molasses, liquors, and medical stores; also several hundred stand of arms, a large number of hospital tents. . . .” Only able to transport so much on horseback, Custer left “the remainder to be burnt.” While at it, they “caused the railroad track to be destroyed for a considerable distance.” Sheridan estimated the Confederates lost 200,000 pounds of bacon and 1.5 million rations with the Beaver Dam Station strike.

Finally, on May 14, Ingalls concentrated his supply train “on the bluffs at Fredericksburg.” For basically the next week “the trains were parked at Fredericksburg, and our depots remained unchanged,” the quartermaster reported. He added, “Several trains of wounded were sent in under the direction of myself and the medical director.”

Maj. William Watson, who served as surgeon for the 105th Pennsylvania Infantry, ended up behind enemy lines in a different way. Watson was left to tend to Federal wounded from the Wilderness fight. Cut off from supplies when the Army of the Potomac moved on to Spotsylvania, Watson found himself in an unenviable position. In an attempt to get help, he sent a letter to an unidentified superior on May 19, 1864. In the letter, Maj. Watson explained his dire circumstances: “I have in charge 275 wounded, including 50 amputations and resections and have neither food, clothing, nor supplies of any kind, the men have been living on hard bread and water for three days, the Coffee was expended on Sunday [May] 12, the sugar on the 13th, and I feel satisfied that many have already died from want of proper sustenance.” Having previously tried other means, Watson ran into red tape and excuses from his side as well as the enemy. Exasperated, the surgeon continued that, “our last cracker was issued this morning and if relief is not afforded the men will die of sheer starvation. I applied to the Confederates, they replied that nothing prevented us from receiving supplies from our own lines.” Watson and his patients finally received help on May 28, when Federal authorities in Fredericksburg sent cavalry, infantry, and 36 ambulances for them.

During the fighting at Spotsylvania on May 12, 1864, pack mules brought ammunition to the front lines for the extened battle. In a fight that saw trees literally whittled in two by bullets, one wonders how many mules fell while serving the army that horrible day.

(Battles and Leaders of the Civil War)

As at Chancellorsville, pack mules came into Federal service. Remembering the horrific fighting on May 12, the 148th Pennsylvania’s Adjutant, Joseph Muffly, wrote, “Ammunition soon ran low, and all day pack-mules, the ammunition cases slung on their backs, were passing up the ravine, and across the dip of the swale [tha] the Salient had been intended to command.” Muffly noted that the fortunate geographic feature also allowed the walking wounded to go to the rear and supporting troops to come forward. “Without it it is hard to see how the difficulty of supplying an advanced line through twenty hours of continuous firing, could have been surmounted,” Muffly thought. The 95th Pennsylvania’s George Norton Galloway recalled, “To keep up the supply of ammunition pack mules were brought into use, each animal carrying three thousand rounds.” Once the boxes were dropped off the officers and non-commissioned officers opened them and “served the ammunition to the men.” Galloway claimed firing four hundred rounds that day.

The Army of Northern Virginia also readjusted its supply lines. After the damage inflicted by Custer’s men to the Virginia Central Railroad at Beaverdam Station, the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad became even more important. Supplies came from Richmond to Guinea Station and then by wagon behind the Confederate lines by way of Massaponax Church Road into Spotsylvania Court House. Henry Beck, a commissary clerk for Gen. Cullen Battle’s brigade notes frequent movements and often issuing rations during the two weeks around Spotsylvania that indicate supplies were being received. For example, on May 9, Beck writes: “Rec’d order from Gen. Ewell to issue rations, started off as soon as I got something to eat, traveled fifteen miles, when we halted near Spottsvy. C.H. Issued to the troops. . . .” Two days later Beck penned, “About 9 A.M. our train was ordered to the C.H. where it remained all day.” On May 14, he noted, “Issued rations this evening, carried them to the front.” On May 19, Beck mentioned Ewell’s reconnaissance movement to the Fredericksburg Road, an important Federal supply line: “The object of this move was, to capture a wagon train, which was reported to be moving towards Fredericksburg. Portion of our corps succeeded in capturing forty wagons, but couldn’t bring them off.” This, of course, was the Harris Farm fighting of which CVBT has saved a portion of the battlefield. Beck finally writes on May 21 about the Confederate fallback toward the North Anna River: “Rec’d orders to move, our train got into motion about 10 A.M. moved on the road parallel with the telegraph road.”

Confederate railroad problems continued with Union cavalry excursions doing damage to the Richmond and Danville line west of Richmond. Even with the soon to be open new Piedmont Railroad at the end of May, which connected Greensboro, North Carolina to Danville, Virginia, supplies arriving from the south met many challenges in getting needed materials to the troops now fighting just north of Richmond.

Conclusion

White canvas covered supply wagons follow infantry cross the pontoon bridge on May 4, 1864, at Germanna Ford as the Army of the Potomac begins the brutal Oveland Campaign.

(Library of Congress)

As was the case at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville earlier in the war, logistics played an important role at Mine Run, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House. As supply issues arose—as they invariable did across all theaters throughout the conflict—the ability to not just acknowledge them, but ultimately overcome them, went a long way toward determining which belligerent would come away the victor. Logistics lessons learned in central Virginia—in establishing and maintaining one’s own and threatening that of the enemy—would receive application in the Petersburg, Shenandoah Valley, and Appomattox Campaigns.

Sources and Suggested Additional Reading

Richard D. Goff. Confederate Supply. Duke University Press, 1969.

Michael C. Hardy. Feeding Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Savas Beatie, 2025.

Earl J. Hess. Civil War Logistics: A Study of Military Transportation. Louisiana State University Press, 2017

Earl J. Hess. Civil War Supply and Strategy: Feeding Men and Moving Armies. Louisiana State University Press, 2020.

Michael A. Martorelli. “Supplying the Armies,” on Essential Civil War Curriculum (https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/supplying-the-armies.html)

Tracy Power. Lee’s Miserables: Life in the Army of Northern Virginia form the Wilderness to Appomattox. University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Parting Shot

Woodcut from sketch by Winslow Homer

Being that this image appeard in print when it did, and that Homer largely depicted scenes within the Army of the Potomac, it may have depicted a scene that occurred during the Mine Run Campaign.

(Harpers Weekly, February 6, 1864)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.