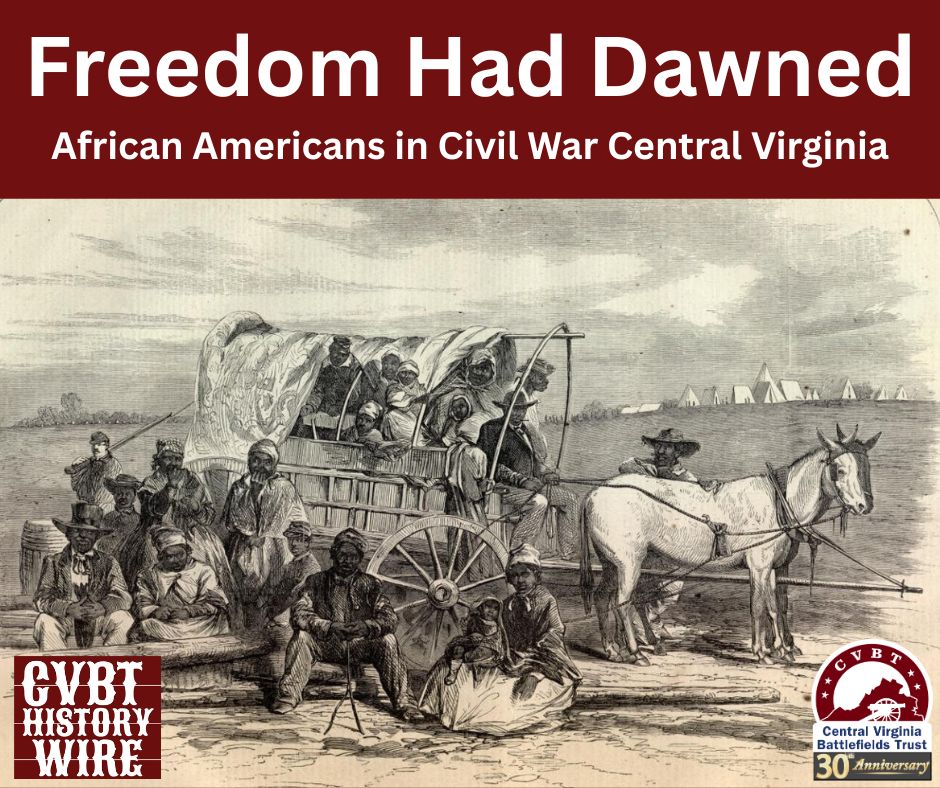

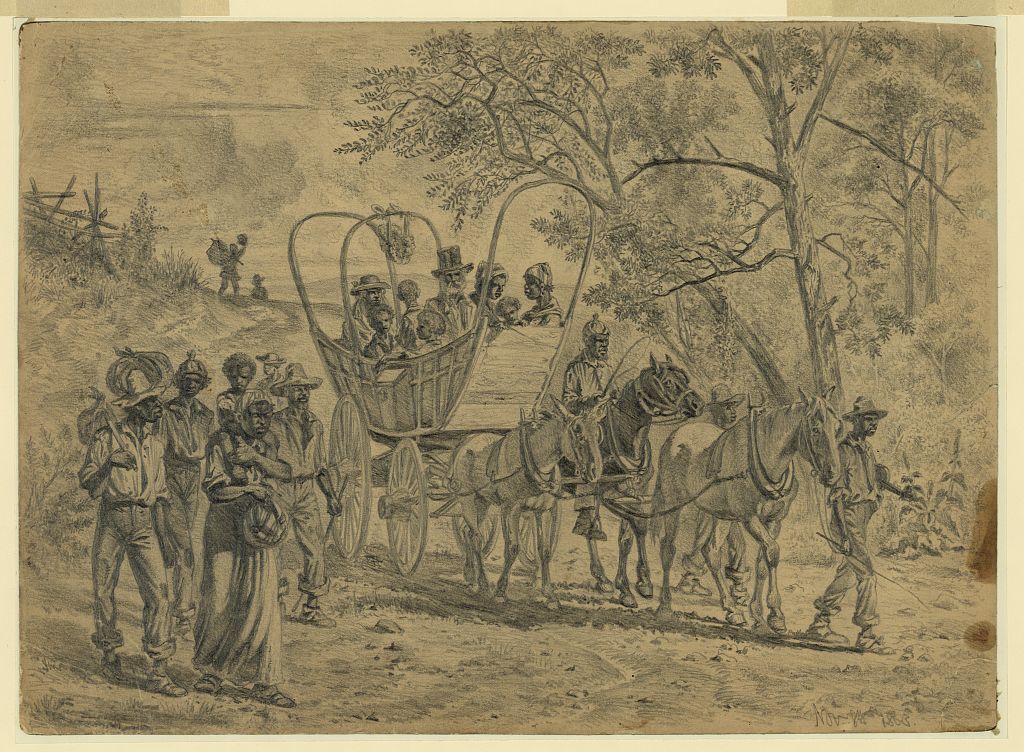

Woodcut from sketch by Alfred R. Waud

Scenes similar to his one occurred often in central Virginia during the Civil War.

(Harper’s Weekly, January 31, 1863)

Introduction

The fact that African Americans would play a large role in how the Civil War changed the society, economics, politics, and culture of central Virginia was a given. They obviously had in the past, and they would continue to do so during the four years of conflict and beyond.

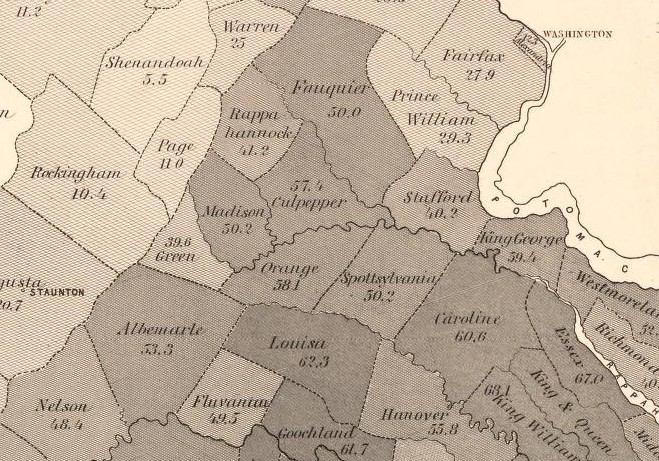

In 1860, enslaved African Americans composed significant if not majority portions of the populations in central Virginia counties. According to statistics from that year’s census, Caroline (60.6%), Orange (58.1%), and Culpeper (57.4%) all had majority enslaved populations, while Spotsylvania (50.2%) was evenly split, and over 40% of Stafford County and one-third of Fredericksburg’s residents were considered human property. Additionally, there were also some 58,000 free people of color in the state of Virginia in 1860, including in all of the above locations. While their numbers remained quite small compared to the enslaved population, limits on their ability to truly experience freedom were heavily restricted by local and state laws.

Several central Virgina counties had majority enslaved populations in 1860.

(Library of Congress)

Both free and enslaved African Americans contributed to the area’s economy through their knowledge, skills, and labor. A traditional view of enslaved people is that they only worked on plantations and farms. Certainly, large numbers did so, but depending on their locations and the outlooks of their enslavers, they also performed a tremendous range of both skilled and unskilled work and lived in town environments as well as rural ones. In addition, and although the thought is repellant to modern sensibilities, the monetary value invested in enslaved people’s very being also allowed their owners to use them for collateral on loans and as a way of transferring family wealth from generation to generation.

The domestic slave trade was also a part of life in central Virginia that stirred the region’s economy. In the summer of 1835, Ethan Allen Andrews visited Fredericksburg. He published a book the following year mentioning that “There is a dealer in slaves who has established himself in this town, where he is driving a very profitable business.”

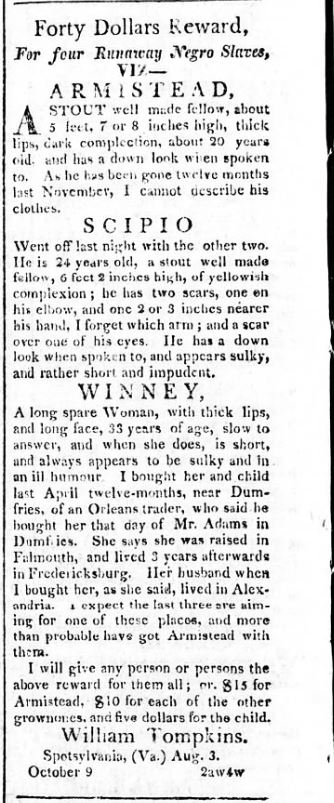

Advertisements in central and northern Virgina newspapers during the half century before the Civil War provide striking evidence of enslaved people’s efforts to gain freedom.

(Alexandria Gazette, November 3, 1812)

Despite the many race-based limitations placed upon African Americans, advertisements in central and northern Virginia newspapers giving notice of enslaved people having fled their situations, or having been captured attempting to do so, provide strong evidence of their efforts to resist bondage and search for freedom. However, before the Civil War, more subtle forms of resistance like holding meetings secretly, breaking tools, feigning sickness, or slowing work paces played out more often than navigating the challenges of successfully escaping bondage.

Freedom Seekers

Changes to the traditional labor system in central Virginia were already well underway by the time President Lincoln declared his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, and then the enactment of the eventual final document on January 1, 1863.

The Union army’s presence in Falmouth helped John Washington escape slavery in April 1862.

(University of Virginia Special Collections)

One of those who made his way out of slavery by way of the Union army was 24-year-old John Washington of Fredericksburg, who left in April 1862. With the help of New York soldiers, Washington, his cousin, and another man made their way across the Rappahannock River to Falmouth. After arriving on the Stafford County shore and answering questions by the Union soldiers flocking around him, Washington recalled, “I was [speechless] With Joy and could only thank God and Laugh.” Washington soon began working as a personal camp servant for Gen. Rufus King, earning $18 a month. In this role he was able to see the changes happening around him. Washington noted that, “Hundreds of Colord people obtained papers and free transportation to Washington and the North, and Made their Escape to the Free States[.] Day after day the slaves came into camp, and every where the ‘Stars and Stripes’ waves they seemed to know freedom had dawned to the slave.” John Washington settled in Washington DC during the war, where joined by his wife, he raised a family.

(Tim Talbott)

Echoing John Washington, soldiers noted the numbers of local enslaved people who came into Federal camps in occupied Fredericksburg during the spring of 1862. One Wisconsin soldier in Gen. John Gibbon’s brigade wrote on May 4, that “It would astonish any one to notice the number of contrabands [refugees], which flock to this army. Every day the roads leading to our camps are lined with fresh arrivals, ‘And still they come.’ A few in comparison to their aggregate number, stay with the regiments, and hire out to the officers and privates. A mess generally hires one or two. They assemble in the evening . . . and hold prayer meetings.” A comrade in the previous soldier’s unit wrote to his hometown newspaper, explaining, “This is a most beautiful country. One could wish for no better. The crops are all in and look finely. Who will take care of them when harvest time comes I cannot tell as most of the laboring class – ‘contrabands’ – are coming to our camps. They come in every day singly and in squads as large as twenty. We give them something to eat and some of the boys get them at very cheap rates to cook and do other things for them. We have 12 or 15 in our company.”

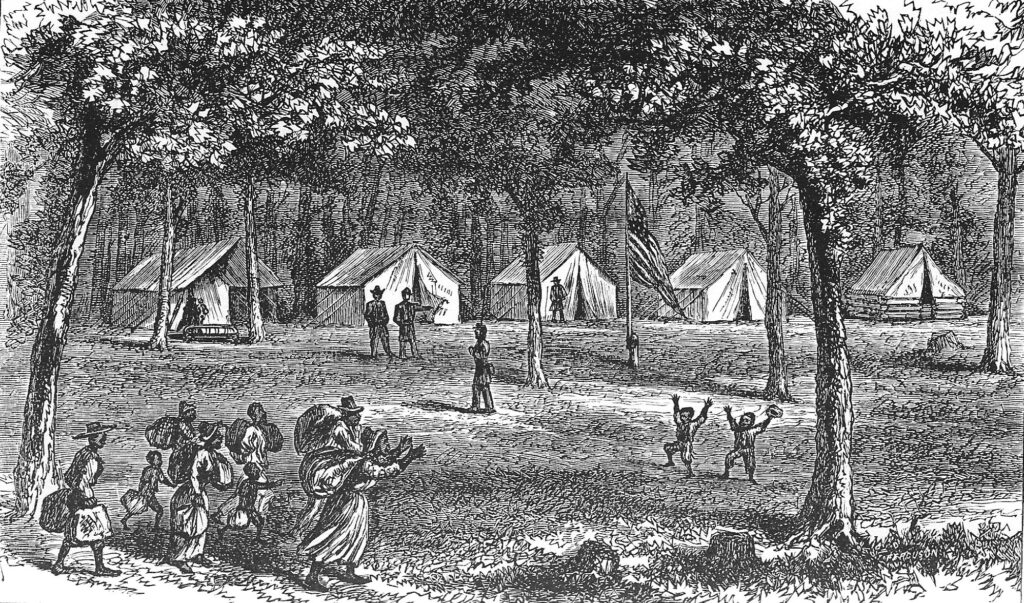

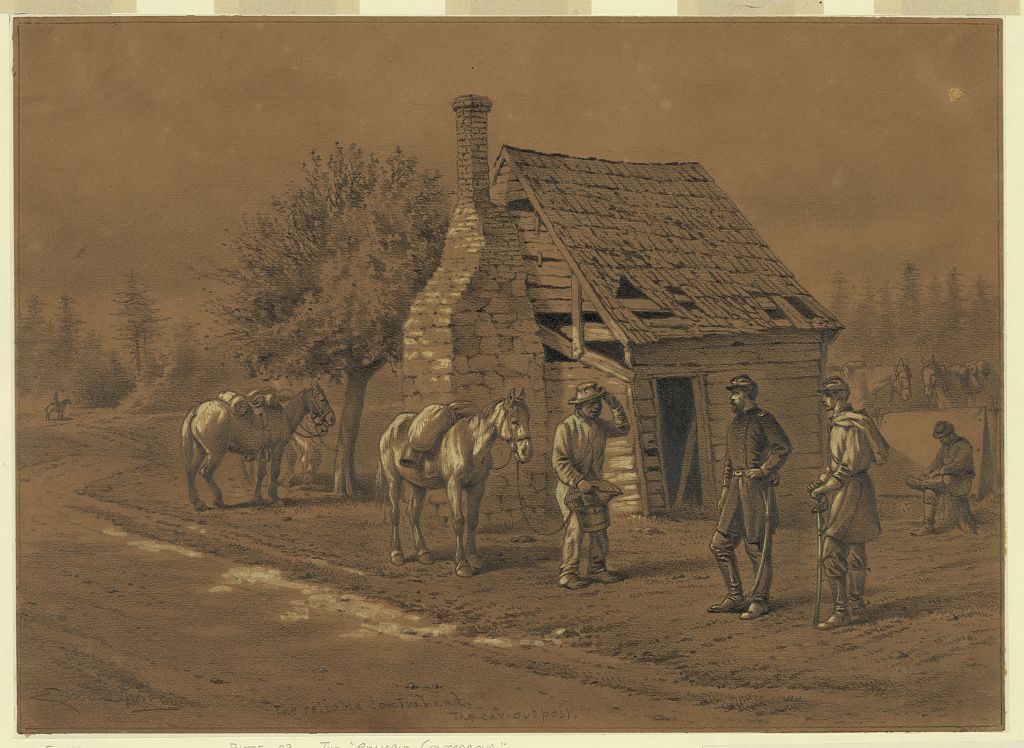

Although sketch artist Edwin Forbes made this drawing on November 8, 1863, similar scenes happened with the Union army’s initial occupation of Fredericksburg in the spring and summer of 1862.

(Library of Congress)

The Federal occupation of Fredericksburg in the spring and summer of 1862 brought opportunities for the enslaved to break their bondage. Writing to his sons in the Confederate army on May 3, 1862, Fredericksburg citizen Thomas Knox complained that, “The Negroes have gone from Stafford and King George & the counties running down to the Bay[.] large numbers have gone from Caroline . . . in fact all down the [Rappahannock] river all the Negroes are gone & daily going[.] No crops will be made in all of our Country deserted by our troops. . . .”

Fredericksburg resident Jane Howison Beale also noted the great change and uncertainty it created for those like her. On May 14, 1862, she wrote in her diary that “The enemy has interfered with our labour by inducing our servants to leave us and many families are left without the help they have been accustomed to in their domestic arrangements.” Interestingly, she also penned that “[the Federals] tell the servants not to leave, but to demand wages.” She, like so many other slaveholders thought this would “prevent the north from feeling the great evil of a useless, expensive and degraded population among them, but it strikes at the root of those principles and rights for which our Southern people are contending and cannot be submitted to, it fixes upon us this incubus of supporting a race, who were ordained of high Heaven to serve the white man and it is only in that capacity they can be happy useful and respected.” Beale had apparently not lost her human property as yet but wrote that “several of my neighbors are left without theirs and we cannot tell ‘what a day may bring forth. . . .’” Half a month later Beale jotted, “The Federal army has abolished slavery wherever it has gone and certainly if [their] design was to punish us by subjecting us to every inconvenience and indignity which an entire rupture of our domestice relations was certain to produce they have succeeded.”

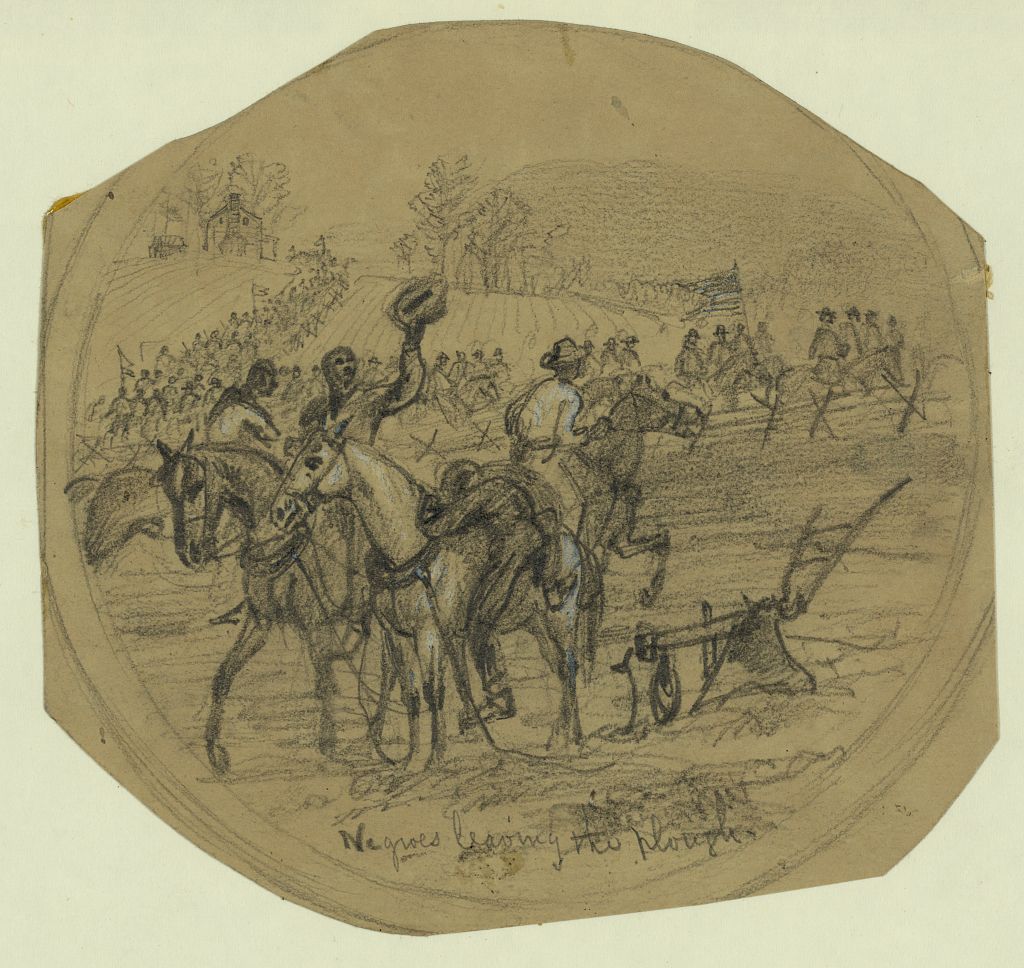

Alfred Waud sketched this scene of enslaved men leaving their field work during the spring of 1864 to follow the Union army.

(Library of Congress)

However, news about the Emancipation Proclamation spread far and wide as January 1, 1863, approached. Susan Caldwell in Warrenton, Virginia, wrote to her husband, Lycurgus, in Richmond at the end of 1862, that, “I do not suppose there will be any [slave] hiring on New Years day—for there are but few servants in town . . . .” The first day of the new year was the traditional day when leasing enslaved people began. Caldwell included, “. . . even now they are talking about this new law after 1st of Jan meaning Emancipation bill—The [enslaved] know every thing.”

Indeed, word of mouth news (what they often called the grapevine telegraph) traveled quickly through enslaved communities. Getting trustworthy information on rapidly changing military situations and troops movements could significantly increase one’s ability to make a successful getaway. Some of the enslaved people from central Virginia’s counties made their way to Alexandria and Washington D.C. A number of men who left the area eventually enlisted in units such as the 1st, 2nd, and 23rd United States Colored Infantry regiments, among others.

(Three Years in the Sixth Corps by George T. Stevens, published in 1870)

As Federal forces occupied additional Confederate territory after the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved people came into Union camps in increasingly large numbers. Surgeon George T. Stevens of the 77th New York, related an example in central Virginia. “Among those who were fleeing from bondage, were two fine boys, each about twelve years of age and from the same plantation,” he remembered. Both said their name was John, and “they were at once adopted into our head-quarters family.” The boys probably worked for the officers as camp servants. Early one morning the officers awoke startled, “the two Johns stood swinging their hats, leaping and dancing in a most fantastic manner,” while vocally exclaiming their joy. “Looking in the direction to which their attention was turned, we saw a group of eight or ten negro women and small children accompanied by an aged colored patriarch.” The group turned out to be the “mothers and younger brothers and sisters of the two boys with their grandfather,” reunited and now free.

In a December 4, 1863, letter to his wife, Daniel Holt, who served as the assistant surgeon for the 121st New York Infantry, commented about an incident that happened on the army’s retreat from Mine Run. “I saw more on the night of that eventful day . . . than I ever saw before, of the cursed institution of slavery,” Holt explained. Stopping at a house to use it for division headquarters and a hospital, the owner “a violent, hard hearted secessionist by the name of Johnson” had fled leaving it occupied by his “wife, two daughters, and several slaves, one of which (a woman with a small unweaned infant at her breast) he paid only a week previously for, the sorry sum of $1,700.”

While using the house for a hospital and some of the nearby slave dwellings for the soldiers to warm themselves, the surgeons were verbally accosted by the white women inhabitants. When it was explained they were using the house to care for sick and wounded soldiers, one shouted, “I hope the house will burn down, and every d—–d yankee in it!” Frustrated, Dr. Daniel Bland told the woman that he did not doubt the house would burn, but that “so far as the d—–d yankees are concerned, we shall have them in good quarters before the torch is applied to your dwelling.”

That night as the army moved on the house was burned. The conflagration spread rapidly and destroyed the slave houses, and Johnson’s tannery, too, which produced leather for the Confederacy. Holt continued, “In little groups stood old and young Negroes looking on as one after another of their long cherished household goods was consumed by the raging element. The most pitiful sight of all was when all had been swept away, to see these poor suffering sons and daughters of a down-trodden race giving vent to slumbering sentiments of freedom.” According to Holt, “these people hailed their deliverance from the hand of their inhumane taskmasters, as did the Israelites upon the return of the year of jubilee. Cold and apparently freezing, as they stood upon the hard frosty grounds in the month of December, with eyes streaming with tears, they blessed the hand of their deliverer and called upon their God to bless ‘de dear gentlemen’ who wrought their deliverance.” Holt wrote that the sight of this, with them “looking forward to the time when families should be re-united . . . and the day when their backs should no longer smart under lash of whip was one which I can never forget. . . .” These newly freed people were transported “in baggage wagons and after conveying them to Culpeper, put them aboard [railroad] cars for Alexandria, where the government has made provisions for all such as they.”

Edwin Fobes sketched this scene showing three African American women and four children in what appears to be a kitchen quarter.

(Library of Congress)

Memories of the war and the changes it wrought stuck with those who endured it. Julia Frazier, born enslaved in Spotsylvania County in 1854, was interviewed in 1937 as part of the Federal Writers Project during the Great Depression. She remembered that “Aftuh the war started an’ the Yankees come, my uncle ran away.” He eventually made his way to Ohio, settled in Springfield and changed his name, Frazier explained to her interviewer.

Serving the Armies

As mentioned earlier in this article, numerous previously enslaved African Americans like John Washington worked as camp servants for soldiers in the Army of the Potomac. The Army of Northern Virginia also utilized both free and enslaved Black men to assist with camp tasks. Period accounts show that Civil War camp servants completed much of the work that the white soldiers (particularly officers) usually disdained such as cooking, laundry, caring for officers’ horses, foraging for supplemental food, carrying water, cutting wood, driving wagons, starting fires, and myriads of other camp duties.

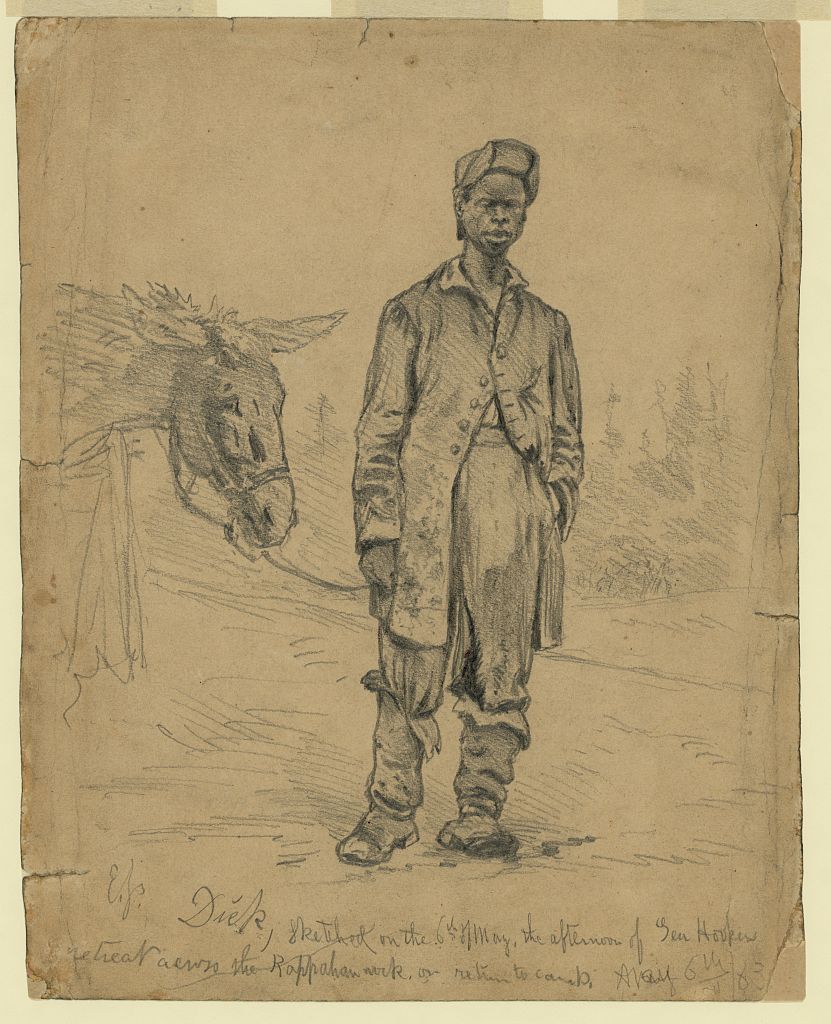

Edwin Forbes sketched this man following the retreat from Chancellorsville. He likely served in some camp servant or teamster capacity.

(Library of Congress)

The 118th Pennsylvania’s Capt. Francis A. Donaldson first met George Slow at Charles Town, Virginia, in the spring of 1862. Slow, had been an enslaved house servant for an owner who had joined the Confederate army. Donaldson found Slow to be “a first rate cook and very handy generally.” By the time Donaldson’s regiment moved toward Fredericksburg the following fall, Slow went off foraging for a couple of days and came back with food and information on “How well posted the Rebs are, [and] knowing more about our movements than ourselves.” During the Battle of Fredericksburg, Donaldson noted that normally “the officer’s colored servants, in time of action, remain well to the rear, but upon this occasion many of them crossed the river with us and took shelter behind the houses.” Slow, “who was always up close during battle . . . never appeared to be afraid,” noted the captain. In case he was killed in the fight, Donaldson was in the process of giving Slow his “watch, money and papers” when a cannon ball hit a building nearby, ricocheted up, and hit a door that was lying in the street. Another camp servant, who happened to be standing on the other end of the door was propelled into the air but fortunately came out of the incident unscathed.

Numerous times in his letters Capt. Donaldson praised George Slow for his many talents, dependability, thoughtfulness, and inventiveness, even calling him “indefatigable,” in camp and on campaigns. Yet, despite the acclaim Slow received, Donaldson could not seemingly shed his bigoted attitude toward African Americans in general. For example, during the Battle of Chancellorsville, one of his fellow officers’ young camp servants, who the captain called Scipio Africanus, and referred to him as “the most remarkable freak of nature to be called human I ever saw,” “became demoralized by fear. . . .” Donaldson ordered the young man to go to the rear. Starting off, a shell hit nearby, “causing him to think it had been fired from a cannon to the rear of us.” Probably suffering from shock, Donaldson described the servant as exhibiting exaggerated physical features and fearing for his life. He apparently ran back to the captain claiming that there was no rear. Donaldson found the situation humorous without probably considering the servant’s situational vulnerability and his youth. Regardless, Donaldson’s many references to camp servants, both in his employment and others, show their ubiquity in army camps and even on the fields of battle.

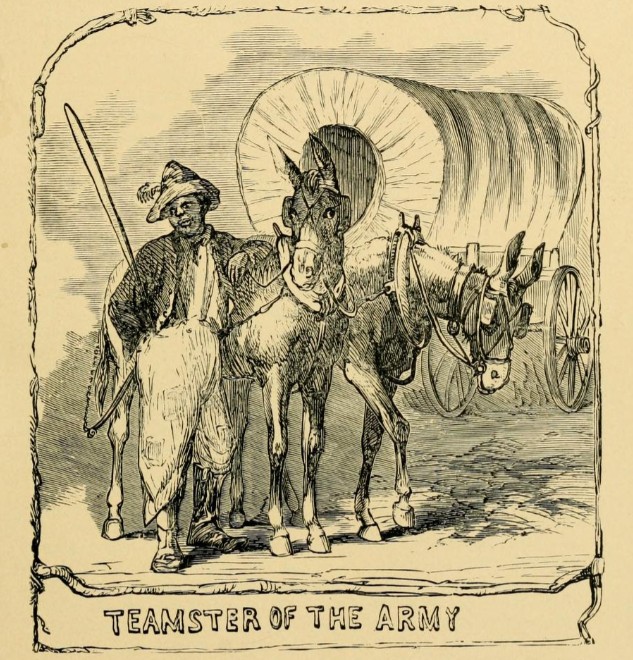

Another vital role that Black men played in the Union and Confederate armies was driving wagons.

(The Black Phalanx: African American soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812, and the Civil War by Joseph T. Wilson, published in 1890.)

Lt. Samuel Burney of Cobb’s Georgia Legion received Stephen as a gift from his grandmother while he was home on a furlough to use as a camp servant. Burney’s letters to his wife often make brief mentions of Stephen. From his camp “Near Fredericksburg,” at the end of November 1862, Burney wrote, “Be sure to send me everything that I have written for if you possibly can. Stephen goes home especially to bring things for me, and so do not be backward in sending.” He closed by asking her to “Write me a long letter by Stephen and send something good to eat.” On January 12, 1863, Burney wrote of the “safe arrival of Stephen with everything he started with,” now back at their Fredericksburg camp. When Cobb’s Legion began the Battle of Chancellorsville, Burney wrote on May 2, that “the negroes are back at Guiney’s Station” and since they had the officers’ clothing, he was unable change. Wounded the following day by a shot above his left eye, the lieutenant was soon sent to a Richmond hospital. Burney wrote on May 7 that “Stephen will be with me to day or tomorrow. I could not bring him on the [railroad] cars, and so I ordered him to put out & walk to Richmond.” Stephen presumably accompanied Burney back home to Georgia for his recuperation, as he continued to serve Burney when the lieutenant eventually returned to the regiment, then in East Tennessee.

While encamped near Fredericksburg Capt. Shepherd Green Pryor of the 12th Georgia Infantry mentioned his enslaved camp servant Henry several times in letters to his wife Penelope. On January 6, 1863, Capt. Pryor mentioned possibly sending Henry home with some souvenirs Pryor had picked up off the Fredericksburg battlefield and asked her to send Henry back with some shirts and a silk pocket handkerchief. Henry finally went about a month later with one of Pryor’s fellow officers, noting that “he is so anxious to come,” and hints that Henry’s time at home will do him good as “he has been quite trifling for the last month,” but also implied it had better, “or Il try and make him.” After about a month at home, Henry returned but did not make it quite to camp before heading back to Richmond to find some misplaced luggage. Henry did not have permission and thus did not have a pass. Capt. Pryor wrote his wife, “[Henry] may get into a scrape and cause us a heap of trouble . . . I am uneasy about him.” Whether that meant Pryor was concerned about Henry getting arrested as a runaway or making an escape to Union lines is left unsaid. Henry finally made it to camp a couple of days later but without the trunk.

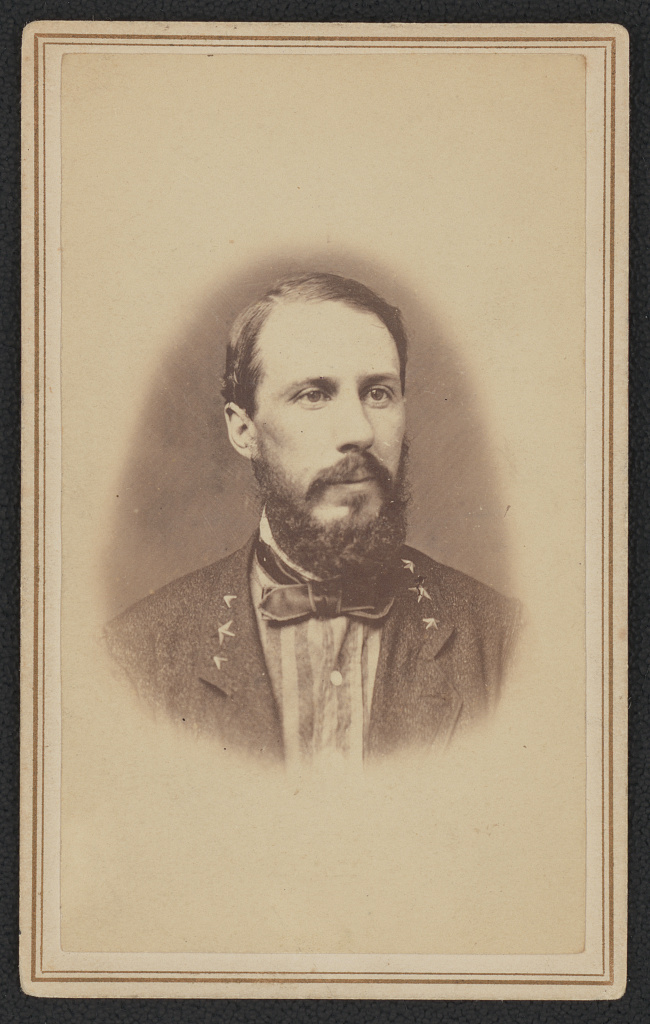

Alexander mentions his enslaved camp servant Charley several times in his memoir, Fighting for the Confederacy.

(Library of Congress)

During the winter or spring of 1862, Edward Porter Alexander, one of the Army of Northern Virginia’s most famous artillerists, “hired for an [h]ostler & servant a 15 year old” named Charley. Alexander described Charley as “medium tall & slender, ginger-cake colored, & well behaved and good dispositioned. . . .” At the Battle of Chancellorsville, Alexander recalled that on May 1, 1863, during fighting on the Orange Plank Road, he was surprised to see “Charley ride up on one of my own horses. . . .” Alexander “was very glad to see him.” The young man brought a “haversack of lunch” and news from Alexander’s wife. As Charley was relaying the information, “there came a crash of a volley of musketry, & all about us the bullets hummed like a swarm of bees.” Charley exclaimed, “Hoo! They are shootin! . . . and disappeared in the direction from which he came so fast that nothing but a bullet could have caught him,” and taking the haversack of lunch, too. While Alexander apparently meant to poke fun at Charley for his perceived lack of bravery by his rapid flight, one has trouble finding any blame with an unarmed non-combatant fleeing the dangers of a battle.

Sources of Information

During the Civil War, time and time again, enslaved and free people of color provided invaluable information to United States army soldiers. Keen observation skills, honed from living under the oppression of slavery and the restrictive laws against free Blacks, translated to intimate knowledge of their local environs and what was happening there. Deftly understanding from early on that a war for Union would also probably result in major changes to the institution of slavery, they provided reliable information freely.

Writing for Gen. Abner Doubleday in April 1862, Capt. E. P. Halstead replied to the colonel of the 46th New York when asked if self-emancipated people were to be returned to their enslavers. Halstead replied, no, “under no circumstances. . . .” He went on to add their value to the army: “they bring much valuable information which cannot be obtained from any other source. They are acquainted with all the roads, paths, fords and other natural features of the country and they make excellent guides. They also know and frequently, have exposed the haunts of secession spies and traitors and the existence of rebel organization.”

by Edwin Forbes

Black men, women, and children provided Union soldiers with vital information about the areas where they operated.

(Library of Congress)

In his memoirs, Capt. Frederick Otto von Fritsch, a staff officer for Brig. Gen. Schimmelfennig (Eleventh Corps) provides an account about meeting an elderly Black man on May 2, 1863, while riding to reconnoiter the area west of Chancellorsville. The captain spied the man, who “slipped behind some trees.” Encouraged to come out from his hiding spot, von Fritsch asked if he lived around there. The old man explained he had for many years. Asking more questions about the roads and the surrounding farms, the man freely shared all put to him noting familiar names and places like Carpenter, Talley, Burton, Wilderness Church, Dowdall’s Tavern, and the Chancellor House. When asked where Lee’s army was, according to von Fritsch, the old man responded, “Look there, don’t yo’ see Mars’ Lee’s men yonder; that’s where they are.” The captain, looking south through his field glasses, could see a column over a mile and a half away. When asked if Lee was with the column, the old man said that his son Jim (who was hiding in the woods so he would not be impressed into working for the Confederates) told him Lee was near but not that close. Capt. von Fristsch told the man to meet him back at Wilderness Church and rode off to confirm the information he had been provided and make a map. Forwarding the intelligence up the chain of command, corps and army superiors largely dismissed the information, believing the Confederates were in retreat, not positioning to make a flank attack. The results, as we now know, were devastating that evening for the Eleventh Corps.

Soldiers in the Cause of Freedom

Not only did the Emancipation Proclamation declare enslaved people in the seceded states “thenceforward and forever free,” it also provided for the enlistment of Black men in the Union army. Organizing, recruiting, and training efforts went forward throughout 1863, and by 1864, the United States Colored Troops (USCT) were ready to assist in the spring campaign of that year occurring in central Virginia.

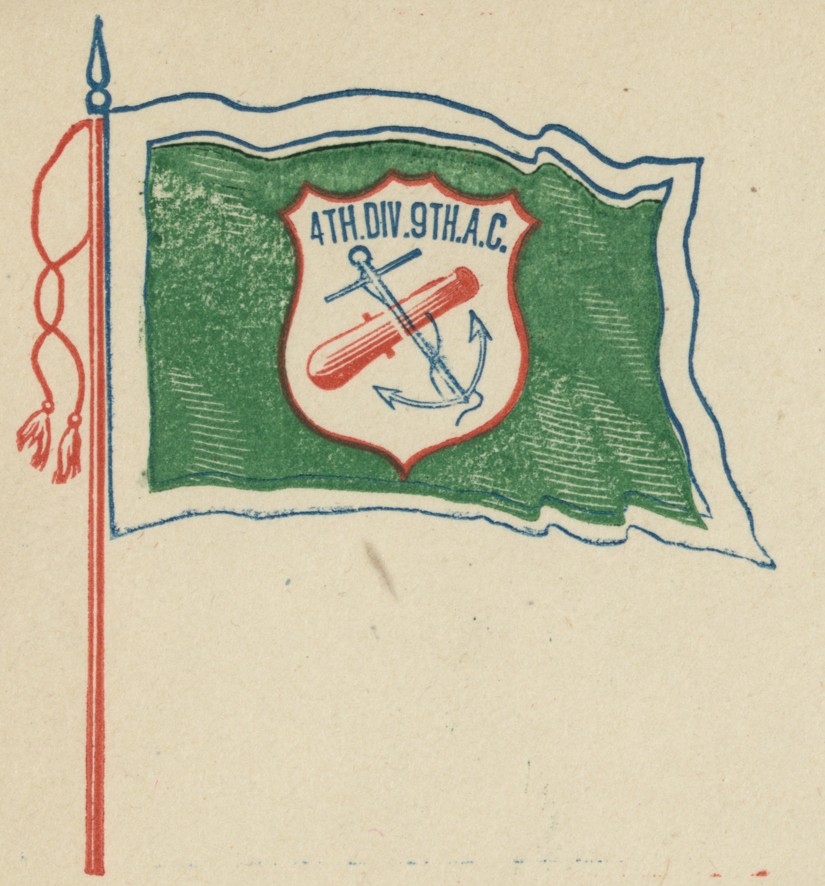

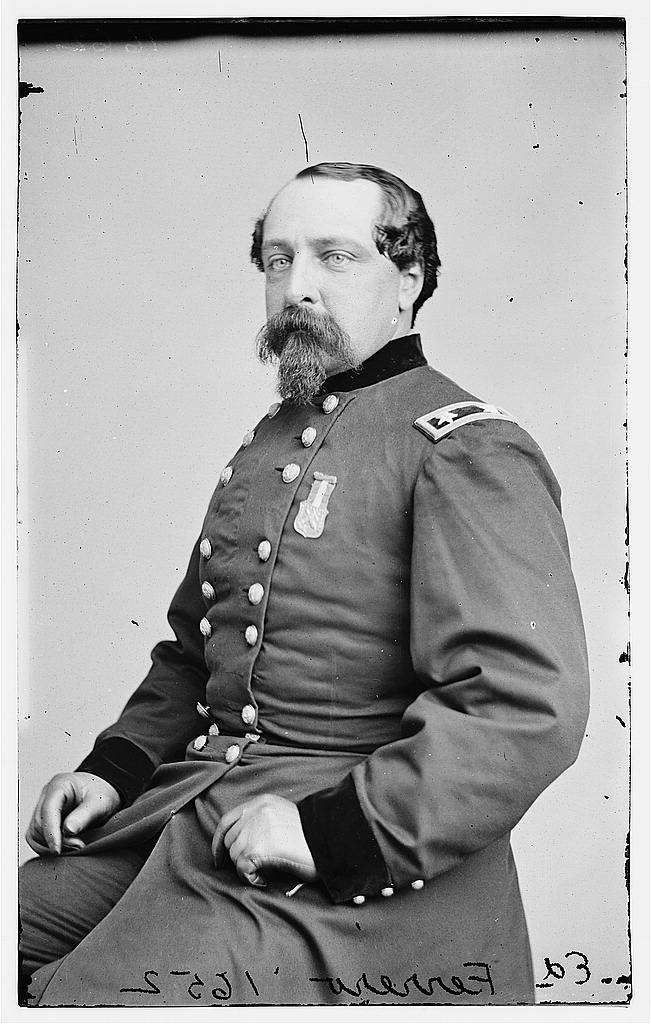

USCTs serving with Gen. U.S. Grant in central Virginia saw combat for the first time as a two-brigade division in the Ninth Corps under the command of Gen. Edward Ferrero in Spotsylvania County. Gen. Ambrose Burnside commanded the Ninth Corps, which at that time was independent of the Army of the Potomac. Col. J. K. Sigfried led the first brigade consisting of the 27th (Ohio), 30th (Maryland), 39th (Maryland), and 43rd (Pennsylvania) United States Colored Infantry (USCI) regiments, while Col. Henry G. Thomas commanded the 19th (Maryland), 23rd (northern Virginia and Washington DC), 31st (New York area) USCI, and the 30th Connecticut.

(Library of Congress)

On May 15, after a fatiguing march protecting a transport wagon train coming to and from Belle Plain Landing, the 23rd USCI, comprised of many men from central and northern Virginia, attempted to catch some rest near Chancellorsville. Their brief repose was interrupted when they received orders to assist the 2nd Ohio Cavalry, who tangled with a brigade of Confederate cavalry under Gen. Thomas Rosser along the Catharpin Road in Spotsylvania County. Rapidly marched to the scene of the action, the African American soldiers fired volleys that drove the Confederate horsemen away.

Gen. Ferrero praised the 23rd USCI in his official report: “On arriving at Alrich’s, on the plank road, I found the Second Ohio driven across the road, and the enemy occupying the cross-roads. I ordered the colored regiment to advance on the enemy in line of battle, which they did, and drove the enemy in perfect rout.”

Ferrero acknowleged the 23rd USCT’s performace at Alrich Farm on May 15, 1864 in an offical report.

(Library of Congress)

Four days later, some of the Ninth Corps USCTs saw additional fighting near the Silver Farm on the Orange Plank Road about a quarter of a mile from where the Alrich Farm fight had occurred. Once more rushing to the scene of the threat, but this time from near Salem Church, the USCTs again drove off “a strong force” of Confederates that apparently included cavalry and artillery. In a memo, Ferrero mentioned capturing five men from Ewell’s corps, and that his own “losses were very small.”

Despite their competent performances in these two skirmishers there were those on their own side who still doubted their ability. Theodore Lyman, a staff officer for Gen. George Meade, wrote a few lines at this time that displayed his prejudices: “As I looked at them [USCTs], my soul was troubled and I would gladly have seen them marched back to Washington. Can we not fight our own battles, without calling on these humble hewers of wood and drawers of water, to be bayonetted by unsparing Southerners? We dare not trust them in the line of battle. Ah, you may make speeches at home, but here, where it is life or death, we dare not risk it. They have been put to guard the [wagon] trains and have repulsed one or two little cavalry attacks in a creditable manner; but God help them if the grey-backed infantry attack them!” Lyman seemed unwilling to see things from the Black soldiers’ perspective; that the battles that the army was fighting were theirs as much as anyone’s, and that their motivations and moral courage was a strong as white soldiers’.

Although limited in combat during the Overland Campaign, the 4th Division of the Ninth Corps would see plenty of action in the drawn out fighting around Richmond and Petersburg during the summer, fall, and winter of 1864. In December 1864, all USCT regiments in the area received reassignment to the Twenty-fifth Corps in the Army of the James. Regiments from the Twenty-fifth Corps were among the first to enter Richmond on April 3, 1865, while other units were present during the fight at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

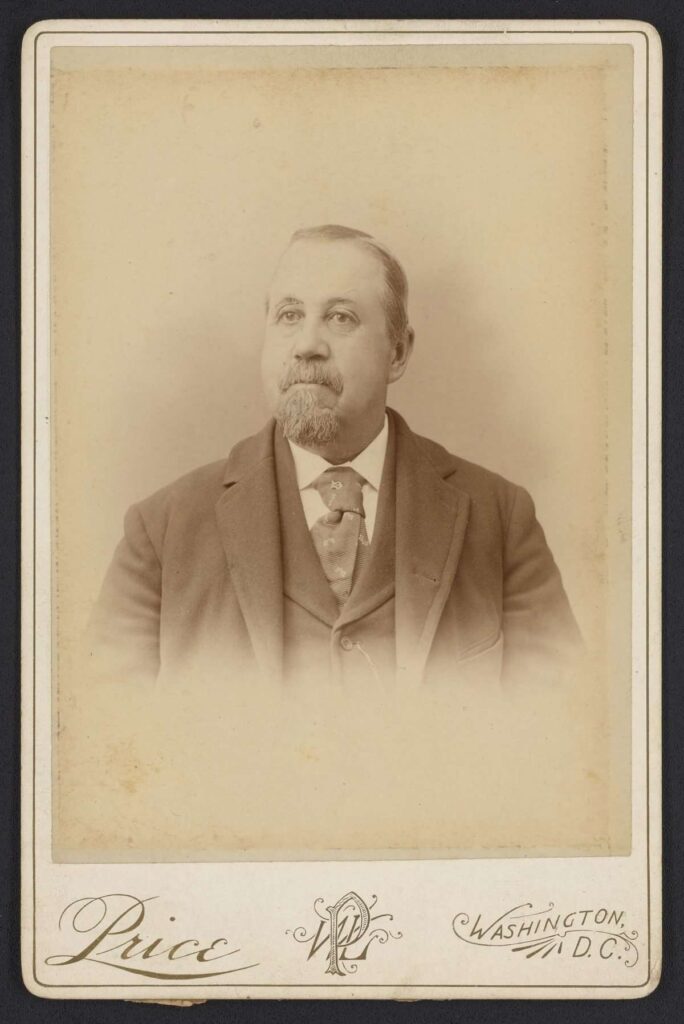

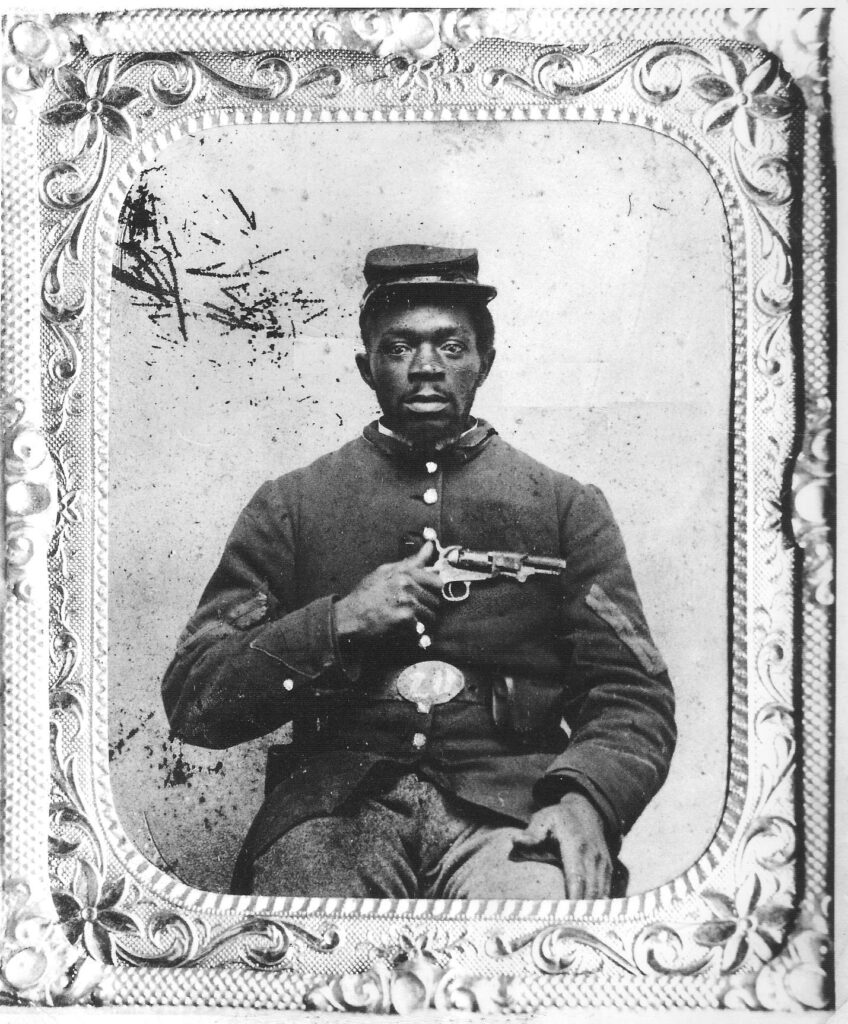

Sgt. Burke was among those who fought at the Alrich Farm on May 15, 1864.

(Public Domain)

According to his service records, Sgt. Nimrod Burke was among the men in the 23rd United States Colored Infantry who fought on May 15, 1864, on the piece of ground that CVBT is currently working to save. Burke and his comrades were the first Black troops to fight against the Army of Northern Virginia north of the James River.

Born a free man of color in 1836, in Prince William County, Virginia, Burke moved with his parents to Washington County, Ohio, in 1854. In Ohio, Burke worked doing farm labor and odd jobs for Melvin Clarke, a Marietta attorney and abolitionist. Now living in a state where he was allowed to learn, Clarke helped teach Burke how to read, write, and do some arithmetic. Burke married Mary Louise Freeman either before or sometime during the Civil War.

Unable to formally enlist as a soldier early in the conflict due to his race, Burke served as a teamster and scout for the 36th Ohio Infantry, a IX Corps unit in which Clarke served as an officer. Although Clarke was killed at the Battle of Antietam, Burke continued to contribute to the Union war effort with his regimental responsibilities. Apparently wanting to do even more, Burke enlisted at age 26 in the 23rd USCT on March 23, 1864, in Washington D.C. and received a promotion to sergeant a week later.

Sgt. Burke’s service records also show that other than a period of illness from August to October 1864, he was always present for duty, including participating in the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, where the 23rd USCT suffered the most casualties among the Union regiments. Burke received a promotion to 1st Sgt. of Company F on October 25, 1864.

After serving at Petersburg and then helping pursue the Army of Northern Virginia toward it ultimate surrender at Appomattox, the 23rd and Sgt. Burke transferred to the Texas-Mexico border, where they finally mustered out on November 30, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the Constitution, outlawing slavery, became law less than a week later when it received ratification.

Following the expiration of his enlistment, Sgt. Nimrod Burke returned to Ohio and his wife, started a family, and worked as a farmer. He died in Chillicothe at age 78 in 1914 and is buried in Greenlawn Cemetery.

Conclusion

John Trowbridge visited the Marye House in 1865. There he met Charles, a formerly enslaved man, who now free, worked for wages.

(Library of Congress)

Writer John T. Trowbridge visited Fredericksburg in the late summer of 1865. While there he stopped at the Marye House. He marveled at the damage: “The pillars of the porch . . . were speckled with the marks of bullets. Shells and solid shot had made sad havoc with the walls and woodwork inside. The windows were shivered, the partitions torn to pieces, the doors perforated,” he wrote.

While surveying the estate, Trowbridge happened upon Charles, a “gigantic Negro at work at a carpenter’s bench in one of the lower rooms.” The man “seemed glad to receive company,” so the two engaged in a conversation. At one point Trowbridge asked, “Where is your master?” The man answered, “I ha’n’t got no master now; Mr. Marye was my master.” Charles further explained that Marye purchased him at an auction in Fredericksburg for $1,200.00. However, the former bondsman quickly pivoted and said, “Now he pays me wages—thirty dolla’s a month.”

Charles continued to tell Trowbridge that he had worked in a mill during the war. People brought in corn for him to ground into meal. Now, another man worked at the mill and Marye was paying Charles to be caretaker of the estate, fixing its broken things. Trowbridge asked, “Are you a carpenter?” Charles responded—probably confidently, and perhaps looking toward the future—“I kin do whatever I turns my hand to.”

During the spring and summer of 1862, alone, an estimated 10,000 enslaved men, women, and children sought freedom by leaving central Virginia. Others preceded them, others would follow. Some, like Charles, never left. Some returned to reunite with family and be in an area they found familiar.

Although Constitutional amendments appeared following the Civil War that abolished slavery, provided equal protection under the law, and granted Black men the right to vote, unfortunately the discrimination that had prompted the need for these amendments did not disappear. In the decades after the Civil War, African Americans faced continued challenges put upon them due to the color of their skin. Segregation customs and laws attempted to maintain an inherently unequal racial separation. Almost 100 years after America’s most tragic event, and largely due to the agency of African Americans themselves, a true change began to develop that witnessed the promise of hope contained in the Declaration of Independence “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Sources and Recommended Reading

Crandall Shifflett. John Washington’s Civil War: A Slave Narrative. Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

Parting Shot

A cropped version of this famous photograph clearly shows three Black men digging graves for Union soldiers who died in Fredericksburg hospitals in May 1864.

(Library of Congress)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.