Sketch by Edwin Forbes.

Graves became common sites for Civil War soldiers in central Virginia.

(Library of Congress)

Introduction

On May 19, 1864, Pennsylvania soldier George W. Belles wrote to his sister to let her know he was well despite having “hard times since we left Brandy Station.” Belles explained, “Our regiment has been in four engagements and lost heavy. Our company lost 15 men in killed and wounded.” Belles took the effort and page space to share that Pvt. “Samuel Spiher was killed in the first days fight. I saw him die in the Wilderness. He was a brave man and I think a Christian soldier.” Belles wished that he had been able “to get something off his body to give to one of his friends [as a keepsake] but I could not for we were hard pressed. . . .” As was too often the case with soldiers after battles, Belles also did not have time to bury his friend. Spiher “and manny of our regiment now sleeps in death in that lonely place far from home and friends,” Belles closed.

Death was an almost constant presence for Civil War soldiers. Comrades were killed or mortally wounded by scores in battle, they died from camp diseases, were occasionally executed for desertion, and perished from non-combat accidents of all kinds. Added to the chaos of war and its seemingly ungovernable nature, these recurring tragedies combined to put soldiers in difficult positions to deal with death in the ways they had as civilians before the war.

At home, loved ones sought to provide what historian Drew Gilpin Faust calls a “good death.” Ideally, the soon-deceased individual would be surrounded by friends and family in a comfortable home environment when the moment of death arrived. After the passing, funeral, mourning, and memorialization followed; all as much to benefit the living as the departed. However, at war and far from home, and as Belles’ account above shows, too often there was no time to suitably prepare a comrade’s body for burial, provide an opportunity for family and friends to come and say goodbye and offer some sense of closure with a funeral, or even bury him and mark the final resting place with a fitting memorial. In Belles’ case, there was not even time to stop and take a small token of remembrance from Pvt. Spiher to pass along to his loved ones.

(Library of Congress)

Civil War burials were particularly prevalent in central Virgina. With the area’s four major battles and the armies’ extended presence during their winter camps of 1862-63 and 1863-64, opportunities abounded for soldiers to expire. The online roster of interments for the Fredericksburg National Cemetery shows not only the names, ranks, companies, regiments, ages, and dates of death for identified soldiers buried there, but many also list where soldiers were originally buried before being reinterred in the national cemetery. Some of the locations include Wilderness Battlefield, Alsop’s Farm, Beverly’s Farm, Miss Fitzhugh’s Farm (Stafford County), Carson’s Farm, Sanford’s Farm, McCoull Farm, Harris Farm, Laurel Hill Farm, and many, many others. These various original burial locations provide stark evidence that the Fredericksburg, and Spotsylvania, Stafford, and Orange County region was literally dotted all over with soldier graves during and immediately following the Civil War.

In this CVBT History Wire post, we will examine some selected accounts that mention soldier burials and that additionally provide some insight into how they reasoned with loss during war.

The Battle of Fredericksburg

As briefly alluded to above, not all soldier burials were from battle wounds. On December 12, 1862, Col. William J. Bolton, 51st Pennsylvania, noted in his journal: “To-night Q[uarter] M[aster] Sergt. Wm. Jones committed suicide by shooting himself.” Col. Bolton provided some vague context for the sad incident by explaining, “Having been for several days in a depressed state of mind he was left back in camp when the regiment was ordered to cross the river. The act was done in the rear of his tent.” Bolton included that “He was buried near the hospital then and later his remains were sent to Norristown.” The following day the regiment went into battle below Marye’s Heights and lost 14 killed and three mortally wounded.

Unfortunately, instances of death also came from accidents preceding combat. Maj. James Wren, 48th Pennsylvania, noted in his diary that on December 12, after entering Fredericksburg, one of the town’s damaged building’s chimneys fell on one of his regiment’s soldiers while camping beside it, injuring him. Wren added, that yet “another Chimney fell & Bruised William Hill of my old Company B & at 2 o’clock in the morning of the 13th of December, he died from his wounds. He was Bruised all over. His Leg was broken in 2 places.” Wren had Hill “buried . . . in the rear of the Baptist Church near whear we war Quartered in town.”

In his diary, Maj. James Wren, 48th Pennsylvania, mentioned burying a comrade in rear of the Baptist Church who had died as the result of an accident.

(Libray of Congress)

Reports from soldiers about the Fredericksburg battlefield indicate the large numbers of dead. William Cowan McClellan of the 9th Alabama noted in a letter to this father on December 15, 1862, the disproportionate number of dead near the Sunken Road. McClellan credited that to the fact that “Our men fought behind Rifle Pits and a stone fence,” and that the Federals “charged our positions seven different times and each time with fresh troops every time being driven back with terrible loss.” Offering a comparison that those at home could understand, McClellan noted, “in a small lot that stood at the edge of the city, not as large as our yard, I counted one thousand dead Bodys.” While McClellan’s count may have been exaggerated for that space, the spectacle must have been horrible to witness.

On the south end of the battlefield, James Jones, chaplain for the 3rd Arkansas, wrote to his uncle John Long on December 15, 1862, about the death of Long’s son and Jones’s cousin, Pvt. Benjamin Long, who served in the 57th North Carolina. Pvt. Long was killed fighting in Gen. Evander Law’s brigade near the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad tracks. Under the circumstances, writing a condolence letter was one way to provide loved ones with a measure of the “good death.” Chaplain Jones reported that “It is my painful duty to write to you a few lines informing you of the Death of your son, cousin Benjamin N. Long. He was killed in a charge last Saturday near the Rail Road.” Jones let Mr. Long know that “I happened to find him yesterday evening (Sunday) just as they were going to bury him, so I got a board and cut his name on it, at his head and feet. He was shot in the head and killed immediately, so the poor fellow died I reckon without much pain.” Knowing that Pvt. Long was located by a relative, buried in a marked grave, and likely suffered little, must have provided a measure of comfort for the family.

Probably fighting in the same general area during the battle, but on the opposite side, Col. Regis de Trobriand explained to his wife in a December 16 letter that the previous day “at three o’clock in the afternoon, there was two hours of truce to help the wounded left between the lines since saturday (two days and two nights!)” Exposed without much aid for so long, unfortunately, “Many of them were dead. . . .” Col. de Trobriand wrote that his men “picked up 92 dead from in front of my line. They were black, hideous, showing the most horrible wounds.” Among the killed were young Lt. Arthur Dehon, who served as aide-de-camp for Gen. George G. Meade, and Gen. Conrad F. Jackson, who lead a brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves in Meade’s division. The colonel lamented that “we did not even have time to bury them. At nine o’clock in the evening, we left without making a noise, leaving these poor devils without burial. The rebels will bury them, and it is high time.” In a follow-up letter, de Trobriand explained a horrific site that he saw on the battlefield where “three soldiers of which the same cannonball had taken away their three heads. They had fallen down in rank, and we have buried them together.” Noting that “We had slept on the ground for two nights surrounded by the dead, who were not buried until later, under a ‘flag of truce;’” the colonel shared the stark difference between the dead and the wounded: “the dead did not say anything and consequently let you sleep in peace; whereas the poor wounded . . . disturbed unceasingly the silence of the night, because they called for help, for some water, etc., etc.”

(Tim Talbott)

Numerous soldiers mention the truces that were called to allow the Federals to bury their dead. The 48th Pennsylvania’s Maj. James Wren recorded in his diary on December 17, while across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, that “All Quiet along the line of our army. We sent a flag of truce over to bury our dead that was not yet Buried & they found that the enemy had stripped our men of all theair Clothing. Stripped naked by enemy. Our men buried 4 hundred & thear is about 250 to be buried opposite our Brigade.”

Amherst, Virginia, artillerist Pvt. Henry Robinson Berkeley also mentioned the truce. Berkeley noted in his diary that during the ceasefire for the Federals to bury their dead, he and three of his comrades ventured out on the battlefield and had “a long and pleasant chat with these Yankees, and told them where they could find four dead Yankees; but the Yankee lieutenant said, ‘Let the [dead] bury their dead and we will have a talk.’” Near Marye’s Heights, while observing the grim work going on, Berkeley wrote, “The Yanks had collected several hundred of their dead on the brink of a deep pit which they were digging to bury them in, when we saw them. It was an awful sight. War is surely awful. I pitied these poor dead men. I could not help it.”

The 11th New Jersey’s Pvt. Alonzo Searing saw his first battle at Fredericksburg. Fortunately, the regiment received orders to guard the lower crossing pontoon bridge on December 13, 1862. However, he soon became an observer to the results of the battle. Searing noted that “a suspension of hostilities was agreed upon in order that both armies could take care of their wounded . . . .” During which, “a strange site was witnessed, Union and Confederate soldiers met midway between the skirmish lines and exchanged coffee for tobacco and newspapers, and even played cards.” At the end of the brief truce the skirmishers “resumed firing at each other.” Searing’s duty on the battlefield also included burial detail. “Many were glad when night came, and after dark we dug one wide grave, and wrapping their blankets around the bodies of our dead comrades, with a few remarks and a brief prayer by our Chaplain, tenderfully and tearfully laid them to rest. At the head of their grave a simple board was placed with their name, company and regiment carved thereon by some comrade’s knife. The burial scene was very impressive, with no light to aid us except the moon and stars,” Searing penned.

Pvt. Roland Bowen of the 15th Massachusetts had previously witnessed soldier burials following the Battle of Antietam and had remarked, “This is not how we bury folks at home.” By Fredericksburg Bowen appeared to have become a bit more calloused. On December 20, Bowen wrote to his mother: “I have been on the battle field since the fight under a flag of truce to bury the dead, so I have a good chance to know something about it. In one mans garden there was 118 of our men just where they fell. The Rebs took off all their clothes that were good for any thing. I saw six in a perfectly nude state, nearly all were partly naked. Such is war.” One wonders what his mother thought after reading that line and Bowen’s additional remark that “One Reb was killed with a canon ball, [and] three days after the Hogs were eating up the body and no one would take pains to drive them away.”

(The Pictorial Battles of the Civil War, 1895)

The burial truce made the press as well. The Richmond Whig reported on December 19: “On Wednesday two detachments came over under flag of truce and requested to bury the dead, which was granted. They found plenty of work to do. Besides the heaps of slain remaining on the battlefield, there were many dead bodies in the streets of Fredericksburg, having been taken from the hospitals and deposited in the first convenient spot. Many private residences in town were used as hospitals by the enemy, and some of the dead were buried in the yards.”

In a rather caustic story by the Richmond Enquirer, written on the same day as the Richmond Whig article, but published on December 23, noted, “At first the Yankees sent over a party of one-hundred, then sixty-five men, and finally on the morning of the second day, five hundred were detailed for this sad, and to those engaged, evidently disagreeable work.” The reporter took the Federal burial parties to task for “the way they performed the last offices for their dead. . . .” The Enquirer, however, was not surprised “that in burying their dead, they satisfied themselves with merely digging long ditches, and pitching them in, heels or heads upwards, as was most convenient, much after the manner, in peace times, of burying dead cattle.” The author mentioned that the burial details were astonished to find so many of their comrades in the nude. He, too, felt it was in poor taste but added a caveat: “Let us hope that if necessity induces our men to appropriate outer clothing that they will hereafter spare the under garments, fitting shrouds for the dead.”

Following the war, Fredericksburg resident Maj. W. Roy Mason provided a short article to the Century Magazine’s “Battles and Leaders” series about the Battle of Fredericksburg. Mason was involved in the truce process and witnessed some of the burials of the Federal soldiers. “Trenches were dug on the battlefield and the dead collected and laid in line for burial. It was a sad sight to see these brave soldiers thrown into the trenches, without even a blanket or a word of prayer, and the heavy clods thrown upon them,” Mason shared. However, what was most disturbing to him was “when they threw the dead . . . into Wallace’s empty icehouse, where they were found. . . .” Mason also shared that soon after the war he was visited at his Sentry Box home by Federals asking about the locations of other burials. They inquired “as to the burial places of the Federal soldiers whom I had found dead on my lot and in my house after the battle of Fredericksburg.” Mason explained, “I had all these bodies, and five or six others found in my yard, buried in one grave on the wharf,” and noting his belief that they were killed Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s men.

Shown in this photo is the fallen roof that covered the Wallace icehouse. Some Federal soldiers were buried in the icehouse.

(Library of Congress)

Mason’s mention of using the Wallace icehouse as a burial location is supported by a story in the Richmond Daily Dispatch issue of December 31, 1862. It read, “We understand that since their evacuation a large number of dead bodies of their soldiers, killed in action in the action of [December] the 13th, have been discovered in an old ice-house near the town where they were thrown by those entrusted with their burial. This was no doubt deemed by the living a convenient mode of interment.” In his article, “Reaping the Harvest of Death,” historian Don Pfanz notes that following the Civil War any soldiers’ remains that were still in the icehouse were removed to the Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

Other Fredericksburg properties became graveyards as well. The 5th Alabama Infantry’s Maj. Eugene Minor Blackford wrote to his father following the battle that he had visited their old home on Caroline Street, which at that time was his uncle John Minor’s home. “It had been used by the Yankees as a hospital, and there was a large pile of arms & legs lying under the cut-paper [mulberry] tree in the yard, and six of the scoundrels were buried in the lawn. I kicked down the headstones and threw them away,” Blackford explained in the letter.

The Chancellorsville Campaign

Photographic evidence like this indicates that many of the Chancellorsville dead were left unburied.

(Library of Congress)

Less than five months after the Battle of Fredericksburg, central Virginia was once again the scene of a major battle. After resting, refitting, and receiving a new leader, the Army of the Potomac, now under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, sought a victory. To do so, Hooker crossed the Rappahannock River and positioned himself on Gen. Robert E. Lee’s left flank. Quick reaction and bold action from Lee helped steal the initiative from Hooker and led to a stunning flank attack by Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall Jackson” on May 2, 1863, that routed the Eleventh Corps.

One of Jackson’s soldiers who fell wounded in the flank attack was Capt. Ujanirtus Allen of the 21st Georgia Infantry. In a condolence letter dated May 8, 1863, Allen’s friend Pvt. Thomas Britton wrote to Capt. Allen’s wife Susan explaining that he remained with the captain until Allen passed away earlier in the day. An obviously distressed Britton wrote, “I will make a box to bury him in if I can get a hammer. there are plenty of planks at this place.” He added, “I will put him away the very best that I possible can help.” Two days later, Britton wrote to his own family in Georgia, also expressing his grief: “I stayed with him and dun everything that was in my power to do for him as long as he lived. I made a box and berried him the best that I could. I hated very bad to give him up. I could not help sheding tears over him while I was covering him up.” Britton buried Capt. Allen at a battlefield hospital near Chancellorsville. In a follow-up letter in June, Britton told Susan Allen, “I put his name very plain on the head board and put a cover on top of the board. There are some 35 or 40 graves where he is berried. he is on the upper side of the grave yard at D. H. Hill’s division battlefield hospital, about 2 miles east of the battle field.”

On May 19, 1863, Jackson’s staff cartographer, Capt. Jedediah Hotchkiss, wrote to his wife Sara about finding the body of fellow staff officer Capt. James Keith Boswell on the Chancellorsville battlefield. Boswell was killed at the time Jackson received his wounds. Hotchkiss penned: “I did not get back to look for Boswell until noon the next day [May 3], in fact the enemy had possession of the place where he was killed until about the time — I found him looking perfectly natural, a smile on his face — I have no doubt he was instantly killed, for two bullets went through his memorandum book in his side pocket & then through his heart. I got an ambulance and took his body to a nice family grave-yard, Mr. [Beverly Tucker] Lacy’s brother’s [James Horace Lacy’s Ellwood] and there had a grave dug & wrapped his over coat closely around him, putting the cape over his head & buried him thus, in all the martial dress, lowering him to his resting place in a shelter tent I picked up on the field of battle, and then spreading it over him — Mr. Lacy made a noble prayer & we finished our sad duty. . . .” Boswell was later reinterred in the Fredericksburg Confederate Cemetery.

(Tim Talbott)

The 9th Alabama’s William Cowan McClellan, who during the Battle of Chancellorsville was serving on provost detail, wrote to this father on May 10 describing the loss of a close comrade at Salem Church. “Our Regt had 24 men killed dead on the field 83 wounded. the heaviest loss of any Regt in the division. Our company had one man killed 18 wounded. Orderly Sgt Batts was killed, he was one of the best friends I ever had, as brave and generous as a man can be,” McClellan explained. Their close frienship comes through as McClellan wrote, “He told me all of his plans. I told him mine. Poor Ted is no more. Oh what feelings crawled upon my memory yesterday as I stood beside his shallow grave and thought of the words he spoke to me a few days ago. While talking a week [before] together he says Mc the next fight I get into I am going to distinguish myself or fall. Poor Ted has paid dearly for going beyond most men.” In a letter a week later. McClellan seems to have pushed his emotions aside, commenting, “All quiet along the River, the enemys Balloons up looking to see if Old Bob is crossing. The wounded have all been sent off, the dead buried and the Army of Northern Virginia ready to whip the Army of the Potomac again if General Lee Says So.”

Writing to his wife on May 17, 1863, Assistant Surgeon Daniel M. Holt of the 121st New York Infantry discussed the loss of Capt. Nelson O. Wendell, who was wounded in the shoulder and then killed by a bullet to the head at Salem Church. Holt was captured during the retreat and held by the Confederates for a few days before being released. Holt penned, “Poor fellow, I saw him with about two hundred others, stretched out before a trench half full of water, into which they were to be thrown at the convenience of their captors. Entirely naked, his greenbacks would have served a poor purpose towards clothing him for the tomb, and as I looked upon all that remained of so pure and worthy a man as he, I thought how well it was that in life he had provided against such a contingency as I now saw in his death.”

With the Federals retreating back across the Rappahannock River, and many of the Confederates returning to their camps south of Fredericksburg, numerous bodies went unburied on the Chancellorsville battlefield. Many soldiers who marched through Chancellorsville enroute to the Wilderness battlefield in early May 1864 noted seeing bones. One New Jersey soldier, Pvt. Alonzo Searing, wrote to his sister on May 11, 1864, that scattered across the Chancellorsville battlefield were “broken guns, battered canteens, torn pieces of knapsacks, haversacks and shreds of clothing; but saddest of all, in every direction, bleaching in the sun, lay the skulls and bones of our dead comrades.” Searing was actually able to identify one friend, Corp. Daniel Bender, by looking “On the under part of the leather visor of his cap . . . he had plainly marked his name, company and regiment.” Bender’s cap was still on his skull a year after his death.

The Battle of the Wilderness

(Library of Congress)

One year later, in the spring of 1864, the armies were at each other once again in the Spotsylvania and Orange County Wilderness. Like at Chancellorsville, the thick woods created challenges for officers and soldiers in terms of command and control. Fought on May 5-6, 1864, the Battle of the Wilderness opened a new campaign and season of killing.

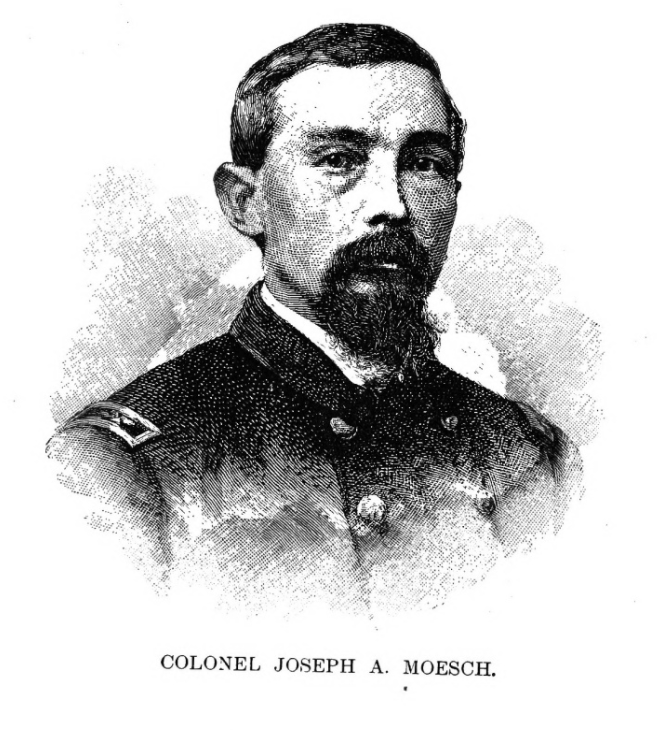

One of the many casualties on the second day of fighting was the 83rd New York’s commander, Col. Joseph A. Moesch, who was killed while leading his regiment into the fight. Moesch, a Swiss immigrant, was initially buried in the cemetery of J. Horace Lacy’s Ellwood planation. The cemetery also contained the amputated arm of Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Chaplain Alfred C. Roe oversaw the burial, leaving the grave unmarked. In 1887, and with Roe’s help, comrades exhumed Moesch’s remains. An account from the sad event gives some evidence of the burial process: “The pine box had entirely decomposed, save a portion of the bottom. Fragments of the poncho tent cloth, wrapped around the body, were found, but crumbled on exposure to air. An entire human skeleton was exhumed, together with pieces of clothing, buttons, denoting state and rank, belt buckle, etc., and upon the bottom of the coffin lay a leaden bullet, Confederate, the missile guilty of that deed of death.” Moesch’s remains were reinterred in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery, where a large stone memorial marker was placed three years later.

While serving as the chaplain for Joseph Kershaw’s Brigade, William Porcher DuBose witnessed Longstreet’s counterattack at the Wilderness on May 6. In a letter three days later, DuBose explained, “Just as our brigade which was in the advance came up, some N.C. troops on the right gave way & Genl. Lee thought the day was gone. Our troops filed rapidly into the woods & faced the enemy. . . . The Yankees followed close but found themselves in contact with more solid stuff & were soon hurled back. This saved the day & in all their subsequent attacks the enemy made no impression upon any point of our lines. But the brigade suffered severely.” Dubose added, “Two of my best friends & the two best officers in the brigade . . . were among the killed.” They were “Cols. [Franklin] Gaillard [2nd South Carolina Inf.] & [James D.] Nance [3rd South Carolina Inf.]. Nance was killed outright. Frank breathed several hours but was never conscious. I had him buried in a graveyard several miles from the field of battle,” DuBose noted.

As the Army of the Potomac transitioned from the Battle of the Wilderness to Spotsylvania, Rev. Hiram V. Talbot, Chaplain of the 152nd New York, took time to pen a condolence letter to Ann Kidder, wife of Pvt. George Kidder, 69th New York, who was mortally wounded on May 6. “It becomes my painful duty to inform you of your husband’s death,” Talbot began. “He was shot, the ball entering the fore part of the left shoulder and coming out the same side of the spinal column about midway. He suffered extremely,” the chaplain continued. Perhaps in effort to offer a measure of comfort, Rev. Talbot wrote, “We have buried him and marked the place.” Perhaps not as comforting was Talbot’s next line, “I think it impossible to send him home.” The chaplain explained that “George was a brave soldier, after he was wounded he fought until he fell from loss of blood. He soon was taken to the rear and [was] cared for best we could. I remained with him most of the time till he died.” When asked if he had any thoughts that should be shared with Anne, George said “Tell her I die for my country, my family and my God.”

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

Many of the wounded from the Wilderness and Spotsylvania were treated in Fredericksburg. Those who did not survive were buried there.

(Library of Congress)

Civil War soldiers faced situations that tested their courage over and over. During the opening phase of the Overland Campaign, Pvt. George Perkins and his 6th New York Battery, while accompanying Federal cavalry, got into a fight with Confederate artillery. During the engagement, Perkins lost two comrades killed and another, a Sgt. Turner, wounded. “Turner’s leg was shot off below the knee and was amputated at the knee joint,” noted Perkins in his diary. Perkins wrote that, “This was the hardest artillery fire I have ever been under.” He continued, “At first I was somewhat flurried but overcame it at last. All the time we were in action I thought of whether I was prepared to die. Tried to be resigned to God’s will if I were to die, fraid I didn’t thoroughly succeed. But I think that my shrinking was only the natural dread of youth. Before we left the field I helped to bury the two dead.”

As was the case on so many previous battlefields, there was not always time to bury the dead at Spotsylvania. After an afternoon of skirmishing along the line near the Spindle Farm, Pvt. John Vautier, 88th Pennsylvania, wrote in his diary on May 13, 1864, “We were posted near the line of battle of the previous days, and the woods were full of dead bodies of our soldiers—the smell from them was sickening.” Vautier was probably glad orders soon came to move to the Union left, leaving the horrific sights and smells behind. Writing the same day, Vautier’s 88th Pennsylvania comrade, Sgt. Charles McKnight jotted in his diary that as they marched along that night they “Passed dead and Wounded rebbes on the road. . . .”

(Library of Congress)

A couple of the most poignant letters from Spotsylvania come from the pen of Lt. Irby Scott, 12th Georgia Infantry. On May 16, 1864, Lt. Scott wrote to his family explaining, “In my second letter I wrote you of Buds [Scott’s younger brother’s] death he died fighting gallantly for his Country and his rights. I had him buried in a garden at the house of Mr. McCool [McCoull] about two miles north of Spotsylvania Court House. His name was marked upon a board at the head of his grave.” Lt. Scott followed up with another letter on May 25. “You have no doubt, if not from my letters, learned the heart rending intelligence of Buds death. He was killed May 10th in the evening about dark the ball entering his head above the left eye, passing out the back of the head. I did not know he was dead until the next morning. I made inquiries that night and was told that he was safe,” Scott explained. Unable to search for Bud that night, Lt. Scott got word the following morning from his comrade Bob Jenkins, who found Bud dead. “I cannot describe my feelings when I learned of his fate. I try to console myself that he died in a good cause, fighting gallantly for his country. He was a brave boy and a more gallant soldier never lived,” Scott proudly penned. Perhaps too grieved himself, Lt. Scott “sent four men to bury him in a garden near by. He had no coffin but I had him wraped in a new tent and a blanket. I have since been to his grave. He is buried at the house of Mr. Neil McCool [McCoull] two miles north of Spotsylvania Court House. At his head upon a board is N.E.S., Co G 12th GA Regt. So it is, he is no more.” Despite Bud’s passing, and as one might imagine, Scott grieved heavily, “I think of him every hour in the day and feel lonely for I always had an eye to his comfort. More than for myself. I would rather if it had been the will of God for him to have been spared.” Instead of proving to be helpful, Scott noted, “I must stop writing upon the subject and try to dismiss it from my mind. It makes me feel so sad. Do not give way to your grief more than you can help. I know this will be hard to do for I loved him as much as you.”

Corp. William Reeder of the 20th Indiana took a few minutes on May 17, 1864, to write his parents back in Peru, Indiana. In his letter, Reeder related his experience in the May 12 battle. “We charged early in the morning and took them by surprise,” he noted. “We took two generals, seven thousand prisoners, and eighteen pieces of artillery. It was a grand thing, but many a man lost his life,” Reeder acknowledged. Reeder also explained, “There is where we lost our captain [John Thomas, Co. A]. He had his leg broken and lay between Rebs and our fire, and when we got him he had eleven shots in him. He was not dead when we brought him out, but he soon died. He lies now about twenty-five yards from where I am, buried under an apple tree.”

(Library of Congress)

On May 18, an effort to break the recently established Confederate line at the base of the Mule Shoe salient resulted in numerous casualties in the units of the Second, Sixth, and Ninth Corps. In many areas of the battlefield located between the lines burial crews were unable to perform their unenviable duties. Capt. Lyman Jackson of the 6th New Hampshire remembered the horrific scene that occurred on ground fought over so desperately six days earlier. “As we came down into the open plain a most sickening sight presented itself. Here were the enemy’s dead, both men and horses, of the battle of the 12th, lying thick in all directions, and loathsomely swollen and disfigured,” Jackson recalled. The captain and his comrades made their way over the ground as quickly as possible “for it was impossible to breathe in that locality,” due to the smell of the decomposing bodies. To make bad matters yet worse, the Confederate artillery let loose “two or three shells and exploded among the dead bodies, and sent their fragments flying in all directions.” Lt. Col. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a staff officer on Sixth Corps commander Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s staff, jotted in his diary that day, “The whole ground stunk horribly with dead men & horses of previous [May 12] fight.”

Conclusion

This photograph shows a slightly different angle from the one three images above of Union soldiers burying men who died in Fredericksburg hosptials from Wilderness and Spotsylvanai wounds. Not the various shaped headboards in the background.

(Library of Congress)

As historian Drew Gilpin Faust notes in her magisterial study This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War: “Death in war does not simply happen; it requires action and agents. It must, first of all, be inflicted; and several million soldiers of the 1860s dedicated themselves to that purpose. But death also usually requires participation and response; it must be experienced and handled. It is work to die, to know how to approach and endure life’s last moments.”

Civil War soldiers and their loved ones at home were certainly attuned to death. Living in a world with its fair share of hazards outside of the war, and with the efficacy of period medicine still leaving much to be desired, they were familiar with the death process. However, the Civil War presented challenges to their conceptions of a “good death.” The conflict saw soldiers die by the thousands on central Virginia’s battlefields, often far from their homes and loved ones. Others, dying amongst strangers in unfamilair environments like hospitals, camp tents, or in squalid prisoner of war camps, greatly disturbed their accepted, acknowleged, and pefered methods for handling death.

As shown in some of the previous accounts, and when situations allowed it, soldier burials attempted to correct some of the war’s impositions on the “good death.” In these cases, especially those involving, dear friends or relatives, great care was taken to provide as proper of a burial as was possible. In many other cases, particularly those involving the enemy or when time and resources were short, the dead received much less care and consideration.

Following the war, national, state, and local entities put forth major efforts to collect the Civil War dead. The Fredericksburg National Cemetery and the Fredericksburg Confederate Cemetery are two obvious examples. But, as we all know, not every soldier received a reinterment. It is in part because of this that our efforts in battlefield preservation are so important.

Sources and Suggested Additional Reading

Drew Gilpin Faust. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. Alfred K. Knopf, 2008.

Meg Groeling. The Aftermath of Battle: The Burial of the Civil War Dead. Savas Beatie, 2015.

Donald C. Pfanz. “Reaping the Harvest of Death: The Burial of Union Soldiers at Marye’s Heights in December 1862 and May 1864,” in Fredericksburg History and Biography, Vol. 12 (2013).

Mark S. Shantz. Awaiting the Heavenly Country: The Civil War and America’s Culture of Death. Cornell University Press, 2008.

Parting Shot

Woodcut print from sketch by Alfred Waud

(Harper’s Weekly, February 3, 1866)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.