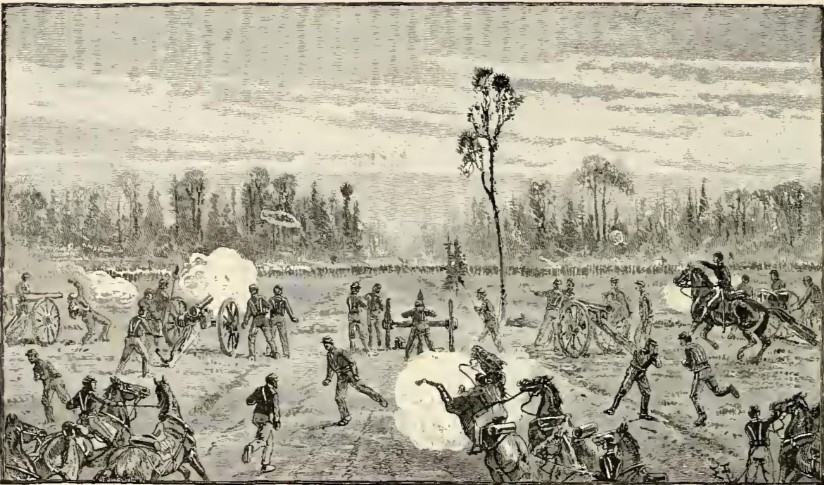

Sketch by Alfred R. Waud

This sketch shows what is probably a gun of Lt. Malbone Watson’s Battery I, 5th U.S. Artillery firing east on the Orange Turnpike.

(Library of Congress)

Introduction

By the time of the Battle of Chancellorsville, artillerists in the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virigina had received a wealth of battlefield experience. Lessons learned from the deadly combat in a string of battles like the Seven Days’ Battles around Richmond, Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg, all honed the armies’ artillery batteries and had them operating as well-oiled machines.

Although the Battle of Chancellorsville was fought largely in the northeastern part of Spotsylvania County’s famous Wilderness, that fact did not prevent the Federal and Confederate armies from using a healthy dose of artillery on each day of the fighting. Primarily confined to the area’s few open fields and the several roadways that transected the battlefield, the armies found numerous occasions to utilize their artillery both offensively and defensively.

In this month’s CVBT History Wire, we will explore some of the accounts that participants left in their letters, diaries, battle reports, and memoirs about artillery at Chancellorsville. For the sake of space this article will focus solely on the fighting at Chancellorsville and will not cover the campaign’s other engagements at Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church.

As a refresher course on Civil War artillery, you may be interested in reading or rereading our previous two-part CVBT History Wire series, “Artillery: The King of Battle,” Part I & and Part II.

(Tim Talbott)

Chancellorsville – May 1, 1863

As the Army of the Potomac’s forces started out from its Stafford County camps for what would be the Battle of Chancellorsville, it did so somewhat handcuffed. After Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker became the commander of the army in late January 1863, he began making a number of positive changes that improved his soldiers’ conditions and boosted their morale. However, one of his decisions proved unwise. Hooker removed his chief of artillery, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, from command of the army’s artillery reserve and parceled it out among the corps. Hooker reassigned Hunt to more of an administrative role. Despite Hunt’s previous strong leadership and performances on the field during the Seven Days’ Battles, Antietam, and Fredericksburg, Hooker and Hunt’s personalities apparently clashed. Hooker’s decision in effect shelved Hunt’s needed guidance over that important branch of service and limited its effectiveness during key situations in the coming campaign.

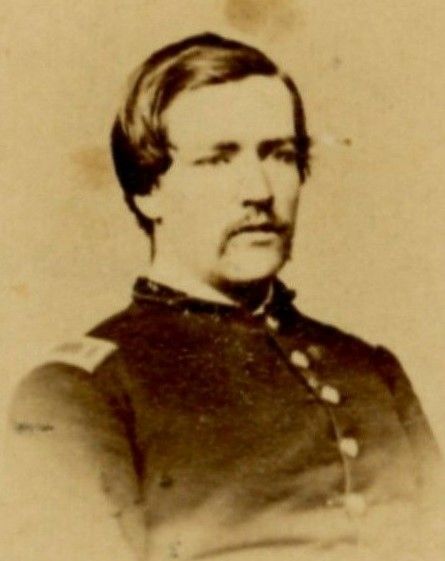

Hunt, shown here as a colonel, clashed with Maj. Gen. Hooker, prompting Hooker to relegate the noted artillery chieftan to an administrative position before Chancellorsville.

(Library of Congress)

The two Federal corps that played principle roles in the first day’s fighting at Chancellorsville arrived on the battlefield east of that soon to be famous crossroads location after making a lengthy march to the west and crossing the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford. From there, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s Fifth Corps took the most direct route to Chancellorsville by crossing the Rapidan River at Ely’s Ford, which positioned it to come into Chancellorsville from the northwest. After crossing the Rappahannock, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s Twelfth Corps crossed the Rapidan at Germanna Ford and then marched east on the Orange Turnpike to Chancellorsville.

Camping around Chancellorsville on the night of April 30, Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ Fifth Corps division received orders to push east on the Orange Turnpike on May 1. Moving with the division was Battery I of the 5th U.S. Artillery, commanded by Lt. Malbone F. Watson. Lt. Watson reported that from the Orange Turnpike, after he fired “one or two shots, I was ordered farther to the front, and was there engaged with the enemy for about an hour” until he received orders to withdraw. In the fighting, his battery lost a limber that received a direct hit from the Confederates and had one horse killed and four others wounded. Meade’s chief of artillery, Capt. Stephen H. Weed only mentioned Watson’s battery as being involved in this part of the battle.

Lt. Watson apparently inflicted some amount damage, as Maj. William H. Stewart of the 61st Virginia Infantry (Mahone’s Brigade) remembered that May 1, 1863, day as particularly trying. In his memoir he wrote: “One solid cannon shot ploughed through the right of our regiment, killing instantly Lemuel S. Jennings and George D. Bright, two of our best and bravest soldiers. On the left [Pvt. John] Warren had his arm blown off by an exploding shell, a fragment wounded me on the leg, and the flesh from Warren’s arm, at the same time, flew in my face, blinding me for a moment, and when I wiped it off with my hand I was sure it was flesh from my own cheeks. I did not learn better until I had washed my face at the spring down the hill, when a comrade told me my face was unscarred.”

(Find A Grave)

Fighting detached from Col. Edward Porter Alexander’s artillery battalion, and now with Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s brigade from Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ division, was Jordan’s Beford (VA) Battery, led by Capt. Tyler C. Jordan. Capt. Jordan remembered that Mahone told him to fight “strictly on the defensive.” However, seeing the enemy “advancing from the opposite ridge; it was a beautiful sight; and I could not resist the temptation to fire into their ranks as they came down the hill, Jordan recalled.” The captain claimed his shots caused confusion and that his were the “first guns fired in this grand battle.” The Federals sent out sharpshooters (skirmishers) which were “were followed immediately by a battery which took position in rear of a farm house. . . .” This was probably Lt. Watson’s 5th U.S. Artillery battery mentioned above. Although one section of his battery had “lost many horses from the fire of the sharpshooters,” Jordan received permission from Mahone to reposition the other section to the right so he could “enfilade this battery and also the lines of the enemy as they advance over the hill.” Permission granted, Jordan made the move but in doing so the Federal battery “directed to us, a terrible, raking fire, and then retired in great haste.” Following the fight, Jordan’s battery was ordered to the rear to refit. Col. Alexander praised Jordan and his cannoneers in his report of the battle.

Pvt. John Walters, serving with Capt. Charles R. Grandy’s Battery of Norfolk (VA) Artillery (Norfolk Light Artillery Blues), noted in his diary on May 1 that as soon as Jordan’s Bedford Battery withdrew, Capt. Grandy took one of the battery’s guns and rode “up to the position left by Jordan and opens on the enemy with canister, he being only about four hundred yards from them.” Soon Grandy sent back to the battery for men to replace those killed and wounded. While waiting for them to arrive, Grandy and Lt. William Peet helped serve the guns. During the action, the battery lost one man killed and five wounded.

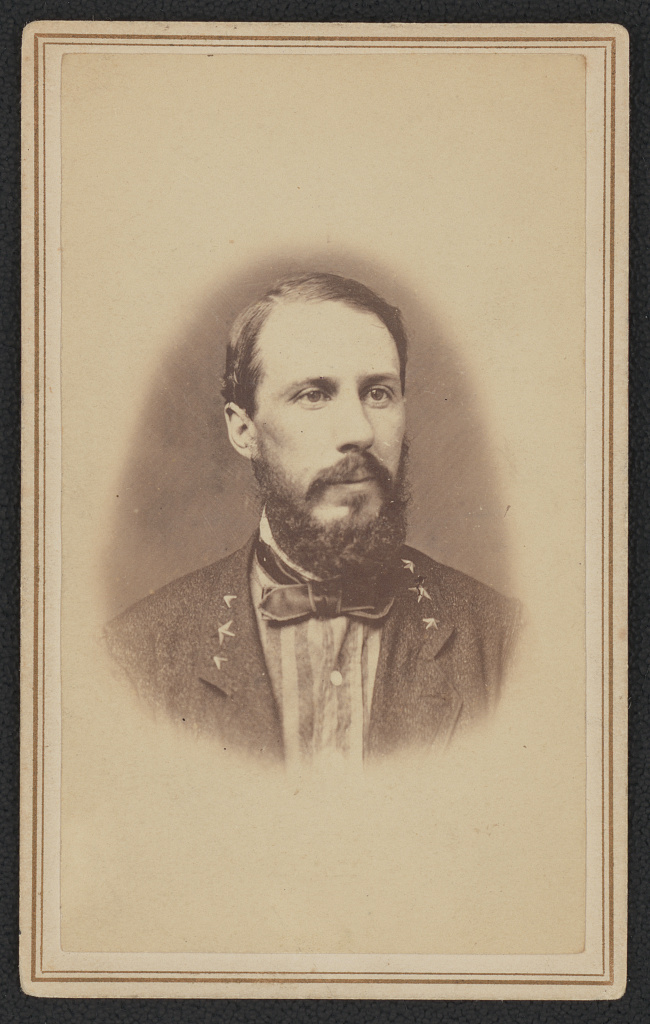

Jordan’s Bedford Battery battled Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ Fifth Corps division on May 1. Jordan is shown in this photograph as a major.

(Library of Congress)

To the south, along the Orange Plank Road (present-day Old Plank Road), Col. Alexander’s battalion of guns battled with Slocum’s Twelfth Corps forces. Alexander pushed forward Capt. Pichegru Woolfolk’s Ashland (VA) Battery to support the Confederate skirmishers. In his memoirs, Alexander recalled an accident that was a common occupational hazard among artillerists working the front of the gun. While loading one of the pieces on the right side of the road in an apple orchard, it went off prematurely, “blowing off the hands of the poor fellow handling the rammer,” Alexander explained. Advancing further west into cleared fields, Alexander saw Slocum’s troops in battle array. He ordered more guns forward but while doing so, he noticed the Federals started to withdraw. No doubt, Slocum had received Hooker’s order to fall back to Chancellorsville, and they were doing so just then. Alexander rode forward “& with one gun, dragged by a ‘prolonge’ rope, hitched to a limber, & a small squad of infantry skirmishers on each flank . . . went down the road to the last turn,” where he could see the Chancellor House. It was swarming with the concentrated Federal troops. While there, he was “harmlessly fired on by a gun behind the breastwork across the road about 300 yards off.” Returning to the area near the intersection with the Furnace Road, the artillerists bivouacked for the night and wondered what the following day held. Artillery fighting was not quite done for the day though.

Robert Beckham, shown here as a lieutenant colonel, commanded Stuart’s horse artillery following the death of John Pelham.

(From The Long Arm of Lee, Volume II by Jennings Cropper Wise, published in 1915.)

Maj. Robert F. Beckham, who commanded Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart’s horse artillery, reported that he had six guns at Catherine Furnace that evening. At around 6:00 p.m., upon orders from Brig. Gen. Ambrose Ransom Wright, “with the view of driving back a line of the enemy’s infantry from the heights, about 1,200 yards in our front” so that Wright’s brigade could occupy it, Beckham went forward on a narrow old road through the woods and fired with three or four guns scattering the Federal line. However, Beckham was not aware of Union artillery in the area, which quickly responded. Beckham’s firing drew “upon us a storm of shot and shell from eight or ten pieces of artillery, well masked by the high, rolling ground on which they were placed,” he noted. Beckham returned the favor, he believed, “with some effect, as it was not many minutes before the rapidity of the firing on the part of the enemy was diminished,” prompting Beckham’s thinking that his fire had been effective. Of the engagement, Beckham added, “I do not think that men have been under a hotter fire than that to which we were exposed.” The damage was significant. Beckham reported that of the artillerists serving one of the guns, only one man remained unscathed. Three men were killed, five wounded, and three horses were disabled.

Capt. Marcellus Moorman of Beckham’s command remembered that due to the thickness of the woods he was unable to find a place to unlimber his guns. Moorman recalled that “I returned to my guns, where I found Generals Jackson, Stuart, and Wright; shrapnel and canister raining around them from the enemy’s guns.” According to Moorman, who had studied under Jackson at the Virginia Military Institute, Stuart advised Jackson, “we must move from here. But, before they could turn, the gallant Channing Price, Stuart’s Adjutant General, was mortally wounded and died in a few hours.”

Lt. John D. Woodbury of Battery M, 1st New York Light Artillery was among those responding to Beckham’s guns. He reported that during the estimated 45-minute barrage, his battery threw 100 rounds at Beckham. Lt. Woodbury’s superior officer, Capt. Robert Fitzhugh, noted in his report why Beckham felt he had never been under a hotter fire. Fitzhugh used Woodbury’s battery, plus two separate sections, both from Battery F, 4th U.S. Artillery, to create a converging fire from three different locations. Although Beckham thought he had silenced Fitzhugh’s guns, it was probably the opposite.

At about the same time that Beckham and Fitzhugh were sparring, Capt. James Breathed’s battery of horse artillery accompanied Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to scout the Federal right. Beckham reported that Breathed “opened fire on the enemy at Talley’s farm . . . with two rifled guns. The enemy were within short range and in heavy force without artillery.” Beckham believed Breathed inflicted a significant amount of damage due to reports from civilians in area following the battle.

Chancellorsville – May 2, 1863

Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard’s Eleventh Corps arrived west of Chancellorsville near Dowdall’s Tavern on Thursday, April 30 and encamped. Holding the Army of the Potomac’s right flank, they received orders on May 1 to march toward Chancellorsville in support of Slocum, but the orders were soon rescinded, and they remained at Dowdall’s. On May 2, various sections and batteries of the Eleventh Corps artillery were placed in defensive positions, most facing south. While the majority of the day passed quietly with the men performing camp tasks, it was merely the calm before the storm, as Jackson’s force of about 28,000 moved toward its position of approach.

Wheeler and his 13th New York Independent Battery experienced Jackson’ s May 2 flank attack on the Eleventh Corps.

(From Letters of William Wheeler of the Class of 1855 Y.C., published 1875)

Among the first surprised in the assault was the 13th New York Independent Battery’s Lt. William Wheeler. In a letter to his mother, Wheeler explained that suddenly there were “shots of skirmishers, then sharp volleys of musketry with rapid firing of canister from the right, where Lieutenant [Joseph] Bohn was with his section, and almost at the same moment our Battery was enfiladed from the right by the enemy’s shells which fell and burst with most fatal effect. The first shell struck two pole horses in Lieutenant [James C.] Carlisle’s section, then burst, and one piece cut in two the pole of my first piece, while another went on and killed a lead horse on the second.” Two more equally destructive shells then hit. Wheeler and his men attempted to turn their pieces to the west, but “it was impossible to fire for fear of killing our own men, who blocked up the road. So we had nothing for it, but to retire to the first hill, where we could take position and accomplish something.”

Lt. Wheeler was able to get his section of guns limbered up and off safely. While working, Wheeler’s mount was hit in the haunch and ran away, so Wheeler started off on foot. Soon he came upon Lt. Carlisle and his section in a mess. Wheeler explained that “all the horses on one gun had been shot, and all but the pole horse on the other, together with two or three of the drivers, and in a fit of desperation C[arlisle] had ordered his men to unlimber and fire canister.” Wheeler attempted to extricate one of the pieces from a ditch but was unsuccessful. Wheeler then advised “Carlisle that the only possible safety was to cut out the dead horses, limber up the gun and take it off with the pole horse alone.” Easier said than done, but they tried. Wheeler continued that “The sergeant cut out the lead and middle horses, and the corporal raised the trail to limber up the gun when a shot struck him, and he dropped the trail on my toes, at the same moment the rebs rushed over the hill and poured a volley into us at very close range, severely wounding poor Carlisle in three places.” Wheeler wondered how he was able to escape and chalked it up to being on foot. “I then made rapid tracks to catch my section; the first hill was full of artillery in position, and firing, and our Battery had found no room to take position, and so was compelled to go further back. At the Third Division breast works I amused myself in rallying our infantry, but they could not be held,” Wheeler wrote.

Dilger received the Medal of Honor for his courageous actions on May 2, 1863.

(Library of Congress)

When Jackson’s attack surprised the Eleventh Corps, Capt. Michael Wiedrich, who commanded Battery I, 5th New York Light Artillery, reported that his battery was prevented from firing immediately due to the denseness of the woods obscuring view of the enemy. In addition, he noted, like Lt. Wheeler did, that when the enemy did come into sight “our infantry, while retiring, rushed in such masses in front and past the battery that it prevented us from some time to open fire. As soon as the infantry was out of our way, we opened with canister with good effect, and checked the advance of the enemy for a few minutes.” However, being outflanked, Wiedrich ordered his guns “to limber up and retire. In the act of limbering, all the cannoneers but 1 of one piece were wounded, and we were compelled to leave it on the field. On another one, after being limbered up and in the act of driving away, the 3 hand-horses and 1 saddle-horse were killed, but by the exertions and good behavior of the men, we succeeded in bringing it off with 2 horses.”

Soon Capt. Hubert Dilger’s Ohio Battery joined Wiedrich in an attempt to slow the attack’s tide as fighting neared the Orange Turnpike/Orange Plank Road intersection. Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz, commanding the Eleventh Corps division to which Dilger was assigned, reported that Jackson’s men threatened the left of Dilger’s battery. Schurz praised the gunner for his courage during the fight. “This battery and that of Captain Wiedrich remained in position until the very last moment. Capt. Dilger limbered up only when the enemy’s infantry was already between his pieces. His horse was shot under him, as well as the two wheel horses and one lead horse of one of his guns. After an ineffectual effort to drag this piece along with the dead horses still hanging in the harness, he had to abandon it to the enemy. The conduct of this brilliant officer was, on this as on all former occasions, exemplary,” Schurz noted. For his bravery under fire on May 2, 1863, Dilger received the Medal of Honor. His citation reads: “Fought his guns until the enemy were upon him, then with one gun hauled in the road by hand he formed the rear guard and kept the enemy at bay by the rapidity of his fire and was the last man in the retreat.”

Brethed, with other portions of Stuart’s horse artillery, accompanied Jackson’s famous flank attack.

(From The Long Arm of Lee, Volume II by Jennings Cropper Wise, published in 1915.)

Accompanying Jackson’s assault and providing additional fire power to the infantry was Stuart’s horse artillery. Capt. Marcellus Moorman remembered that while awaiting the attack and upon not receiving orders for his battery he approached his old VMI professor Jackson, saluted and asked if he was to go forward with the attack. According to Moorman, Jackson replied, “Yes, Captain, I will give you the honor of going in with my troops.” Maj. Beckham reported Gen. Stuart ordered him to place two pieces in the Orange Turnpike under Capt. Breathed that were to advance with the infantry and two other pieces “immediately in rear were kept as a relief to Breathed from time to time, the width of the road not allowing more than two pieces in action at once.” Finally, “Captain Moorman’s battery was still farther in rear, to be brought up in case of accident,” Beckham wrote.

Jackson ordered Beckham “to advance with them, keeping a few yards in rear of our line of skirmishers.” Despite the road being narrow and encountering obstacles placed to impede their progress, Beckham explained that his artillery was “able to keep up almost a continual fire upon the enemy from one or two guns from the very starting point up to the position where our lines halted for the night.” Using every piece of elevated ground they could find along the way, the horse artillery “advanced under a perfect hail storm of canister, but the men moved on steadily, apparently unconscious of any danger.” As they approached the Federal position at Chancellorsville, Beckham reported that he kept up a “desultory fire . . . for a short time, which caused all of the enemy’s batteries in front and on our right to open upon us.” Understanding that his limited artillery firepower could not match that of the Federals, he ordered the firing stopped and withdrew the horse artillery to the rear and Col. Stapleton Crutchfield, Jackson’s artillery chief, brought up his guns “of longer range and heavier caliber.”

Specifically, Lt. Col. Thomas Carter received orders from Col. Crutchfield to bring up his guns. Carter reported that “We were now within 1,000 yards of the Chancellorsville field, where the enemy had massed on open ground some twenty or more guns.” Carter explained that due to the thickness of the woods on each side of the Orange Turnpike “it was impossible to bring more guns to bear” than the two Napoleons and one Parrot rifle he currently had in action. After exchanging some shots with the Federal artillery Gen. Hill ordered Carter to cease firing.

Crutchfied, the artillery chief for Jackson’s corps, was mortally wounded on the evening of May 2, 1863.

(From The Long Arm of Lee, Volume II by Jennings Cropper Wise, published in 1915.)

As the first of the wreckage from the Eleventh Corps retreat started arriving at Chancellorsville, Hooker relied on Capt. Clermont Best of the 4th U.S. Artillery to stem to tide. Best reported that he “gathered all of our [Twelfth Corps] batteries . . . massing them on the ridge in rear of the First Division, and posting in position with them some of the fragments of the Eleventh Corps batteries. . . .” In all, Capt. Best assembled about 34 artillery pieces. Hooker approved the placement and gave Best permission “to open fire whenever I deemed it necessary.” Still, Best had to be careful of those Eleventh Corps soldiers still coming in. In addition, Best explained, “I was obliged to fire over the heads of our infantry force, ranged in parallel lines about 500 yards in front. It was an operation of great delicacy,” he noted.

(From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. III, published in 1884)

Things were hectic that evening just to the south at Hazel Grove, too. There, the 6th New York Independent Battery, serving under Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, and assisting the Third Corps also encountered the fleeing Eleventh Corps. While facing to the northwest, “then the bullets began to whiz about our ears. All the batteries in the field opened, ours also,” noted Pvt. George Perkins of the 6th. Perkins jotted, “Our horses frightened by the sudden firing got excited and a portion of them were lost, mine among the rest. The caisson horses ran away and overtured the gun limber scattering the ammunition on the ground.” However, by rapid firing, soon the enemy withdrew and his battery received orders to cease firing. Having lost his blanket and overcoat in the confusion, he found an abandoned battery wagon in their front which luckily contained one of each.

Fighting beside Pvt. Perkins and the 6th New York Battery was Battery H of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery. Corp. George Merrell noted in his own diary about the evening of May 2 that “We were in an open field and the first we knew the rebels came out of the woods and fired a volley of musketry at us and then charged on our battery. We got our guns in position as soon as we could and gave them canister the best we could, and after firing an hour the best we could we drove them back with great slaughter.” Merrell wrote that he and his fellow cannoneers “lay by our guns all night and did not get much sleep for we expected the enemy to charge our battery again. But they did not this night.”

Commanding the aritillery for the Second Division of the Third Corps, Capt. Osborne called the May 3 fighting at Chancellorsville, “desperate beyond the point of description.”

(Find A Grave)

Back along the Federal line to the north at the Orange Turnpike, things were in even greater disarray as that road east was the quickest means of retreat for the discombobulated Eleventh Corps. Wading into the wild rush was Third Corps, Second Division artillery chief Capt. Thomas W. Osborn. In a letter to his brother on May 8, Osborn wrote, “I could not move the guns without injuring the men as they would not give way.” Osborn gave it a minute or two hoping they would clear but they did not, so he moved on up. “I presume a few men may have been hurt but if they were I could not help it,” he explained. He estimated that the Eleventh Corps mass “extended about a half mile before we passed through it.” Osborn placed two batteries on the left side (south) of the Orange Turnpike and one on right. He ordered a section (two guns) under Lt. Justin Dimick even further forward, placed “to command the road in front of our [battle] line.” Around 9:00 p.m. Osborn saw Confederate horsemen in the road and ordered the forward section to fire. The other batteries took up firing as did the Federal infantry line, and soon the Confederates replied, causing quite a commotion before finally settling down again.

Jackson was wounded by accidental musket fire from the 18th North Carolina as the flare up began. It was also about this time that Col. Crutchfield was wounded badly in the right leg breaking a bone. According to Lt. Col. Carter, the Federal artillery did “considerable damage . . . to my battalion, still in column of pieces on the turnpike, behind” his three forward guns.

Movements by both sides throughout the remainder of the night and early morning hours of May 3 brought sporadic, and at times heavy, artillery and infantry fire.

Chancellorsville – May 3, 1863

Confederate artillery placed at Hazel Grove had an excellent position to enfilade Union infantry and artillery at Fairview, which is visible in the distant left background.

(Tim Talbott)

While the armies’ artillery actions on May 1 and 2 had certainly been significant, they paled in comparison to what would happen on May 3.

During the night of May 2, Hooker and Lee both had serious concerns about the centers of their lines. Lee was worried about the Army of the Potomac’s Third Corps position at Hazel Grove dividing the two parts of his army, whereas one of Hooker’s greatest worries was the exposed position that the Third Corps held. Enduring the Eleventh Corps rout earlier that day prompted Hooker to order Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles to withdraw the Third Corps to the defensive lines at Fairview.

As daylight began to break on May 3, only some infantry under Brig. Gen. Charles Graham and artillery commanded by Capt. James Huntington still held the Hazel Grove high ground position when Brig. Gen. James Archer’s Tennesseans and Alabamians attacked it. Huntington reported that “The battery was served as rapidly as possible and kept the front clear, but though the infantry on our left fought gallantly, it was forced back.” Despite firing canister and shells with the fuses removed for quick bursts, Huntington’s lack of infantry support exposed his flank. With some Confederates already in his rear, Huntington “ordered the battery to limber to the rear, and moved off.” The only avenue of escape was across a challenging hill and through a “piece of marshy ground and over a bad ditch.” Huntington was able to get two pieces to safety, “but the horses of the others being shot and unable to get them over the ditch, and being exposed to the fire of our own men as well as that of the advancing enemy, they were necessarily abandoned.”

Pegram’s batteries helped clear Federal forces from Hazel Grove on the morning of May 3.

(From The Long Arm of Lee, Volume I by Jennings Cropper Wise, published in 1915.)

Anticipating Confederate attacks from the west, Capt. Clermont Best had his 34 guns entrenched during the night and early morning of May 2 and 3. He reported, “the digging subsequently proving much protection.” He believed that his position was so strong that it “could not have been forced” had Hazel Grove remained in Union hands. In his opinion the Confederate capture of Hazel Grove “was most unfortunate.” It allowed the enemy to turn their guns on Best “with fearful effect, blowing up one of our caissons, killing Captain [Robert B.] Hampton [Battery F, Pennsylvania Light Artillery], and enfilading General Geary’s line.” Best explained that despite this, and with almost all of his ammunition exhausted, he was able to maintain his position until about 9:00 a.m., “when finding our infantry in front withdrawn, our right and left turned, and the enemy’s musketry already so advanced as to pick off our men and horses, I was compelled to withdraw my guns to save them.”

In addition to those disadvantages that Capt. Best listed, his artillerists were also laboring under a couple of others. First, they were forced to shoot over their infantry in front of them to hit the enemy for much of the fighting. Second, they were also taking fire from the rear from artillery in Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s and Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ artillery units. That Best’s guns were able to stand as long as they did is impressive.

To Capt. Best’s right, Capt. Thomas Osborn, commanding the Third Corps, Second Division artillery, fought his guns along the Orange Turnpike. In a letter to his brother, Capt. Osborn noted of the May 3 fighting, “It would be useless for me to attempt to describe the fighting at this point. It was desperate beyond the point of description.”

Lt. Dimick was still in an advanced position on the Orange Turnpike when the morning Confederate attacks began. Osborn reported that, “From the first moment I learned of the position of the enemy, I played upon him with the artillery, the section in the road [Dimick] using very short fuse and canister as the enemy moved to and fro.” Osborn explained that despite “the persistent attacks of the enemy” and “under a galling fire from the rebel sharpshooters and line of battle, Lt. Dimick showed the skill and judgement of an accomplished artillery officer and the intrepid bravery of the truest soldier.” Osborn noted that Dimick was able to hold the position “for upward of an hour, his men fighting bravely, but falling rapidly around him (his horse being shot under him), and our infantry crowding back until his flanks were exposed.” Osborn finally ordered Dimick to limber up and withdraw.

The move came with cost. Attempting to extricate his two guns “horses became entangled in the harness, and in freeing them [Dimick] received a shot in the foot.” Dimick hid the wound from his men as a means to keep them calm in the pressing situation, “but in a moment received one in the spine,” which caused his death two days later. Of Lt. Dimick, Osborn stated, “As a line officer he has shown fine abilities, and on the battle-field was unsurpassed for gallantry.”

The 23-year-old Dimick held a forward position with two guns along the Orange Turnpike where he received a mortal wound on May 3. His superior officer said Dimick was “unsurpassed for gallantry.”

(Find A Grave)

Lt. George B. Winslow, Battery D, 1st New York Light Artillery also fought as part of Osborn’s command. During the morning’s see-saw fighting, Lt. Winslow reported that at one point “the enemy came down in solid masses, covering, as it were, the whole ground in front of our lines, with at least a dozen stands of colors flying in their midst.” Winslow ordered his guns loaded with solid shot, and after the Federal infantry cleared his front, “fired at about 1 ½ degrees’ elevation. The effect was most terrible. A few rounds sufficed to drive the enemy in great confusion up the hill, whereupon our infantry again charged and took several stand of colors.”

Note the numerous lunettes in front of the guns.

(Tim Talbott)

Soon, Confederates crossed the Orange Turnpike and attacked Winslow’s battery from the right. He explained that they “came out of the woods not more than 100 yards from the muzzle of my guns, planted their colors by the side of the road, and commenced picking off my men and horses.” Winslow wrote that “when a sufficient number had rallied around their colors, my guns having been previously loaded with canister, I gave the order to fire. In this way they were repeatedly driven back.” As Confederate reinforcements arrived, they closed to “not more than 25 or 30 yards from my right gun,” when Osborn ordered Winslow to limber up and withdraw. He did so “from the left successively, continuing to fire until my last piece was limbered.”

Another of Osborn’s artillerists, Lt. Francis Seeley, Battery K, Fourth U.S. Artillery reported the havoc his battery endured after falling back to near the Chancellor House. Ordered by Third Corps artillery chief Capt. George Randolph “to check the advance of the enemy,” Seely “loaded the guns with canister, and reserved my fire until the enemy was within 350 yards of my position, and then opened with terrible effect, causing their troops to break and take to the cover of the woods on my left and front, where we followed them with solid shot until the ammunition in the limbers was exhausted.” Lt. Seely reported loosing seven killed, 39 wounded, which was almost 40 percent of his battery. In addition, he lost 59 horses killed or disabled.

Alexander’s guns at Hazel Grove exhibited amazing range during the May 3 fighting.

(Library of Congress)

From their advantageous position at Hazel Grove, Col. Alexander’s guns were able to pummel the Federal forces gathering around the Chancellor House. Their most famous victim was Gen. Hooker himself. While receiving a dispatch on the porch of the house, a shell slammed into one of the pillars knocking it into Hooker and sending him senseless to the porch floor. While the direct strike to the pillar where Hooker was standing was likely by chance, another shot hit the blanket where the general rested just mere moments after he left the scene for the rear. Other shots hit the house catching it on fire, proving Alexander’s guns had near perfect range from Hazel Grove. Some Confederate guns quickly moved up to the Fairview plain.

In attempt to buy some time for Hooker’s withdrawal from Chancellorsville to a new position just to north, artillery was ordered into place near the Chancellor House. Among the arriving units was Battery E, 5th Maine Artillery, led by Capt. Charles F. Leppien. After Captain Leppien was mortally wounded, Lt. Greenleaf T. Stevens took command of the battery. Lt. Stevens reported that even before they could unlimber, they came under “a most galling fire.” Stevens noted that “[the Confederate] artillery was served with great vigor and remarkable precision, opening with canister, spherical case, and shell.” He added that, “The ground being hard, and affording no cover, their projectiles ricocheted, causing the loss of a large number of horses, and inflicting many severe wounds upon the cannoneers and drivers.” With their ammunition expended, one limber blown up, 43 horses killed or wounded, and the artillerymen depleted by casualties and exhausted from serving the guns, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock had nearby infantrymen attach the prolongs to the guns and pulled them to safety by hand.

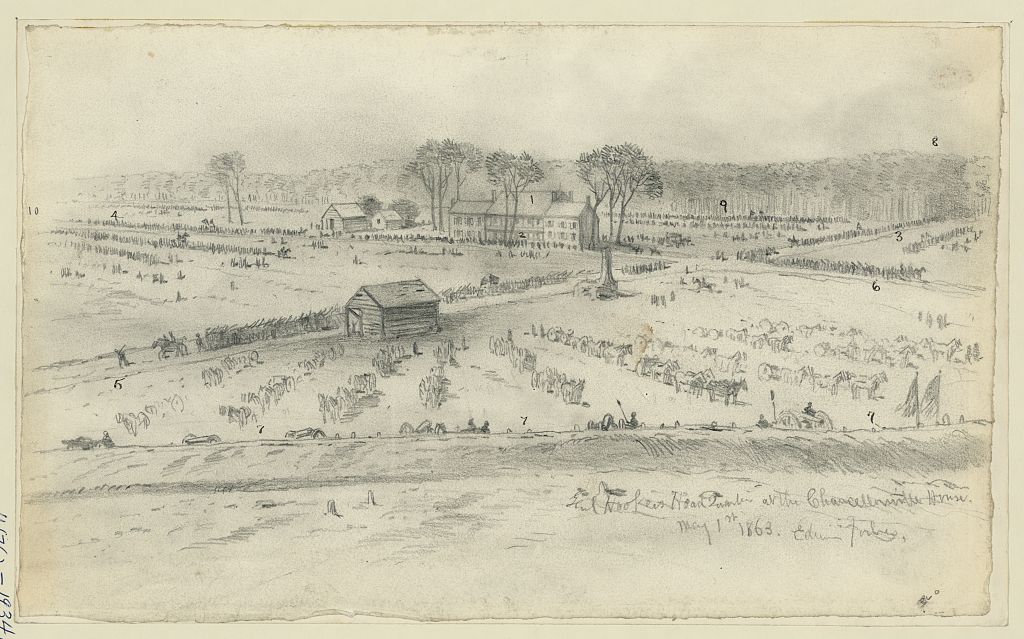

Sketch by Edwin Forbes

Although this sketch depicts May 1, it gives a good picture of the open ground around the Chancellor House. Note the artillery in the foreground earthworks.

(Library of Congress)

Conclusion

Hooker ordered his army to fall back to a newly established line of works near the Bullock House maintaining the crossing point at U. S. Ford should the army commander choose to fully retreat. From their new position, the Army of the Potomac’s artillery continued to play a key defensive role for the remainder of May 3 and 4.

As the fighting raged near the Chancellor House on May 3, and with Gen. Hunt near Banks’s Ford, Hooker turned to First Corp artillery chief Col. Charles Wainwright to take charge of the artillery and wrote out orders giving the colonel power to make decisions for that branch. On May 4, Wainwright meet with Hunt and “turned matters over into his hands.”

On the evening of May 5, after a council of war with his corps commanders, Hooker decided to retreat back across the Rappahannock into Stafford County. On May 12, Hooker, learning a hard-learned lesson from the battle, chose to go to a brigade organization for the artillery and led by Gen. Hunt. The decision, maintained when Gen. Meade took command on June 28, 1863, proved highly beneficial in the army’s next big fight at Gettysburg.

Sources and Suggested Additional Reading

Herb S. Crumb and Katherine Dhalle, eds. No Middle Ground: Thomas Ward Osborn’s Letters from the Field (1862-1864). Edmonston Publishing, 1993.

Gary W. Gallagher, ed. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Earl J. Hess. Civil War Field Artillery: Promise and Performance on the Battlefield. Louisiana State University Press, 2023.

War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. 25, Part 1. Historical Times, Inc., reprint 1971.

Ken Wiley. Norfolk Blues: The Civil War Diary of the Norfolk Light Artillery Blues. Burd Street Press, 1997.

Parting Shot

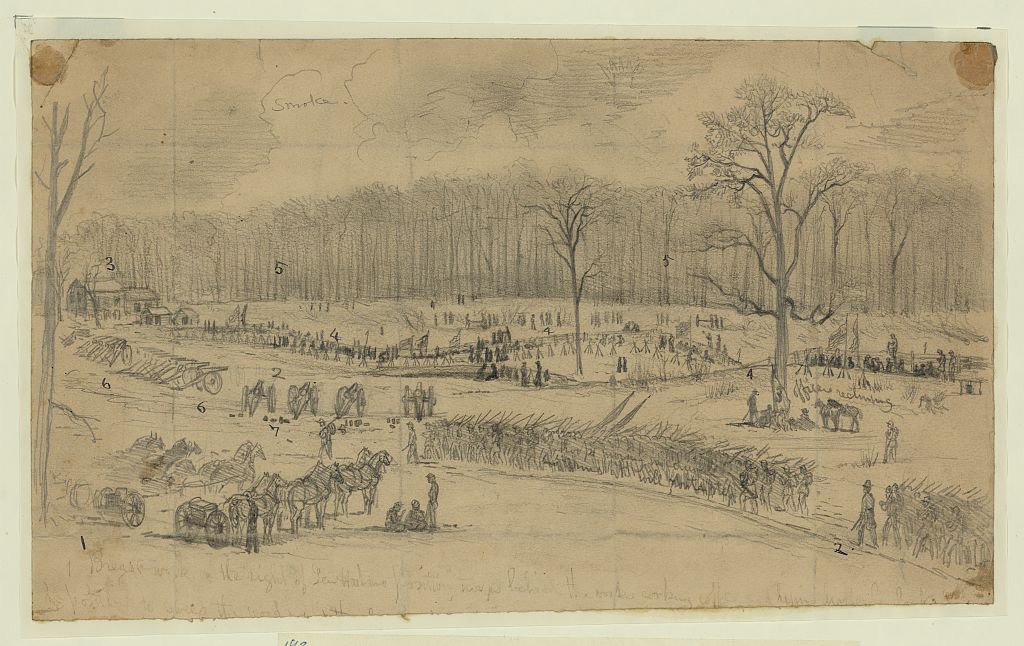

Sketch by Edwin Forbes

This sketch shows the Army of the Potomac’s fall back line near the Bullock House.

“(Key). 1. United States ford road. 2. Ely’s ford road. 3. the White House where General Hooker was brought after being injured at the Chancellorsville House. Used as a hospital during the battle. 4. Union breastworks. 5. Woods through which the Confederates charged and where a great many wounded on both sides were burned to death. 6. Batteries in position ready to sweep the ground in front. 7. Ammunition in rear of the guns ready for an emergency.”

(Library of Congress)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.