Being that this image appeared in the January 3, 1863, issue, it was probably observed by the artist during the late November period before the railroad from Aquia Landing to Falmouth was back in operation.The same issue shows the pontoon train on its way to Falmouth

(see below).

(Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 3, 1863)

Introduction

“Upon the faithful and able performance of the duties of the quartermaster an army depends for its ability to move. The least neglect or want of capacity on his part may foil the best-concerted measures and make the best-planned campaign impracticable. The services of those employed in the great depots in which the clothing, transportation, horses, forage, and other supplies are provided, are no less essential to success and involve no less labor and responsibility than those of the officers who accompany the troops on their marches and are charged with the care and transportation of all the material essential to their health and efficiency.” – Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, U.S. Quartermaster General

Many Civil War enthusiasts put little thought into how an army transports, feeds, and supplies itself and how in turn those factors could determine success or failure. Rather, the vast majority of time spent studying the war goes into rehashing the strategy and tactics of the battles and campaigns. Part of the reason for this is that until quite recently Civil War logistics has received relatively little scholarly attention. However, it would do us all well to remember that there would not have been battles and campaigns without the soldiers’ tools of war. Everything soldiers needed, including but not limited to weapons, ammunition, clothing, shelter, and food (for humans and animals), had to be supplied and brought to them, distributed out to them, transported for them, or carried by them.

It was not only necessary to get what the armies needed to them in a timely manner, they also had to receive the right things at the right time. For example, it did little good for an infantry regiment needing .58 caliber rifle ammunition to receive cartridges intended for a .69 caliber musket. Efficient supply was more key than just supply, and much of that depended on a slew of pre-printed paperwork forms and a competent army bureaucracy. Gangs of clerks and technologies of the day, like steam power and the telegraph, helped increase efficiency.

Paper pushing clerks helped make the U.S. army’s supply bureacracy run fairly smooth.

(Library of Congress)

As the war ramped up, the need for large amounts of supplies obviously necessitated increased production. Whether it be rifles, blankets, hardtack, or oats and hay, things had to be manufactured and grown in order to supply the armies’ voracious needs. Supply also requires transportation and distribution. Raw materials like iron ore and hemp had to be transported to manufacture centers before they could become artillery shells and rope. Similarly, but on the other end of production, artillery pieces made in factories in Pittsburgh or Richmond had to be transported to where they were needed in the field. Again, modern technology such as railroads and steamboats had the ability to speed or retard transportation and distribution depending on their condition and maintenance.

Supply organization in both the United States and Confederate States armies involved primarily three different departments or bureaus: quartermaster, commissary, and ordnance, all with fairly specific roles. The Confederates also had a Bureau of Niter and Mining in addition to the other three. Each was responsible for the acquisition of materials, which usually came through purchase, impressment or capture. Once received, the departments were also in charge of the distribution of the materials to members of the company, regiment, brigade, etc. The quartermaster departments were typically responsible for the transportation of materials to the units.

The quartermaster department handled things like uniforms, shoes, tents, wagons, horses and mules, animal forage, harness, horseshoes, and the like. The ordnance department managed arms and munitions. The commissary department oversaw food for humans. As one Union officer wrote: “The Commissary Department is the great heart that sends the life-blood bounding through the veins of an army. Other departments are useful and necessary, but this is absolutely indispensable. To it the soldier looks for his daily food; without it no army could exist, no victories would be won. The wise commander will see that the haversack, not less than the cartridge-box, is well filled; for the hungry soldier, however abundantly supplied with powder and ball, is lacking in the one great essential to success-physical strength and endurance.”

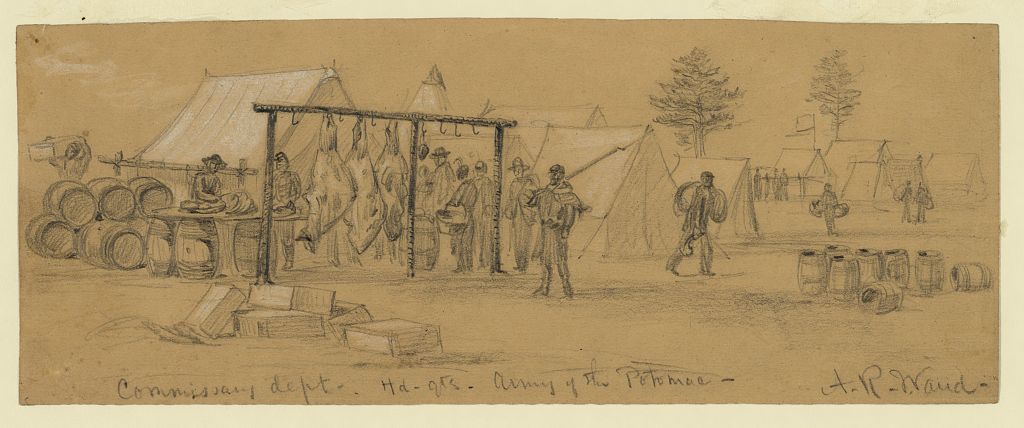

Sketch by Alfred Waud

(Library of Congress)

While all of these roles at each level of army organization were important, many of their practitioners felt underappreciated and additionally burdened with pressures to perform well. Maj. Harry Hammond, quartermaster for Gen. Samuel McGowan’s South Carolina brigade, would write later to his wife while at Petersburg: “Six days in the week you are not able to do what is needed, work as you will, for that you get positively unmitigated, universal blame. The seventh you are fortunate, and you are simply ignored. I know you will say that this is true in a great measure of all vocations, that is so, but in some to a much greater extent than others, and in none I believe more so than it that of a property officer [quartermaster] connected with an army. There is never any chance of doing more than is expected of you, and setting that off against your failures.”

Getting the needed things to the troops was one of the largest hurdles to overcome. Quartermasters employed different means of transportation. In his book Civil War Logistics: A Study of Military Transportation, historian Earl J. Hess divides the conflict’s transportation options into four basic groups: river-based, rail-based, coastal shipping, and wagon trains.

Due to central Virginia’s geographic location and natural features, all four of these methods came into play at some time and at some level during the region’s campaigns.

In this CVBT History Wire post, we will examine some of the logistical challenges the armies faced during their 1862 and early 1863 campaigns in central Virginia.

Fredericksburg Campaign

(Library of Congress)

From the Army of the Potomac’s initial occupation of Fredericksburg in April 1862, to their departure in September of that year, and then the army’s return in November 1862, logistics proved key to their potential for success. Establishing a supply base at Aquia Creek Landing on the Potomac River allowed large coastal ships and smaller river vessels to deposit military materiel there from centers of manufacturing and storage depots. The supplies could then be transported to Falmouth either by wagon or via the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad line after the bridges they had burned during their evacuation in September were rebuilt.

Of course, a primary issue that plagued the Army of the Potomac upon its arrival in November 1862 was getting across the Rappahannock River from Falmouth into Fredericksburg. A series of miscommunications and missteps between Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, and engineers and quartermasters in Washington, resulted in a train of pontoon boats being delayed, which in turn allowed Confederate defenders time to concentrate south and west of Fredericksburg.

Moving the pontoons overland was no small feat. Historian Frank O’Reilly described the wagon-carrying boat train as consisting of “40 pontoon wagons, each toting a boat 31 feet long and 5 2/3 feet wide.” Enormous amounts of tools and bridging materials accompanied the boats including “37-foot-long timber balks, cable lashings, rack sticks, oars, boat hooks, pumps, and spring lines.” Also required were an assortment of anchors, flooring boards, chains, abutment sills, entrenching tools, and even forges. A team of six harnessed horses or mules pulled each pontoon wagon.

(Libray of Congress)

Moving these heavy monstrosities during the best of weather was no small task, but upon departing Washington, the engineers ran into a steady rain that quagmired the operation by the time they reached Occoquan Creek. Bridging the swollen stream after much difficulty, they traveled on to Dumfries where most of the boats were offloaded and transported via the Potomac River to Aquia Landing and Belle Plain Landing. The largely emptied wagons traveled on to Stafford County via the sloppy roads. Some pontoons arrived at Belle Plain on November 22, but not being informed that they were coming by that route, no means of transportation was immediately available to get them to the army at Falmouth until two days later.

Woodcut based on sketch from Henri Lovie

(Frank Leslie’s Illustrarated Newspaper, January 3, 1863)

Getting the short portion of the railroad line from Aquia to Falmouth up and running also took time and tremendous effort. The line was finally operational by November 27. The following day, Maj. James Wren of the 48th Pennsylvania noted in his diary: “We had the Locomotive to make her first trip today from Acquia Crick. She brought supplies for the army & she made 3 trips today.” The 11th New Jersey’s Col. Robert McAllister noted likewise on November 30, “The cars have come whistling through here. Now our supplies will come without so much hauling by wagons.”

However, before it opened, the lack of rail transportation put a bit of pinch on the Army of the Potomac, which had largely arrived at Falmouth a week before. For a time, only wagons were available to carry supplies and food for soldiers and army animals. Relief soon came, but not before some soldiers complained about the lack of rations, while others resorted to foraging the Stafford County countryside to supplement their diets. The animals suffered too. A soldier in the 51st New York wrote on December 9, “Now it has become the turn of the poor horses to do without food. Some days, they have gone with nothing to eat and no shelter, but there they stand, tied to a post, looking as if they had been forsaken.”

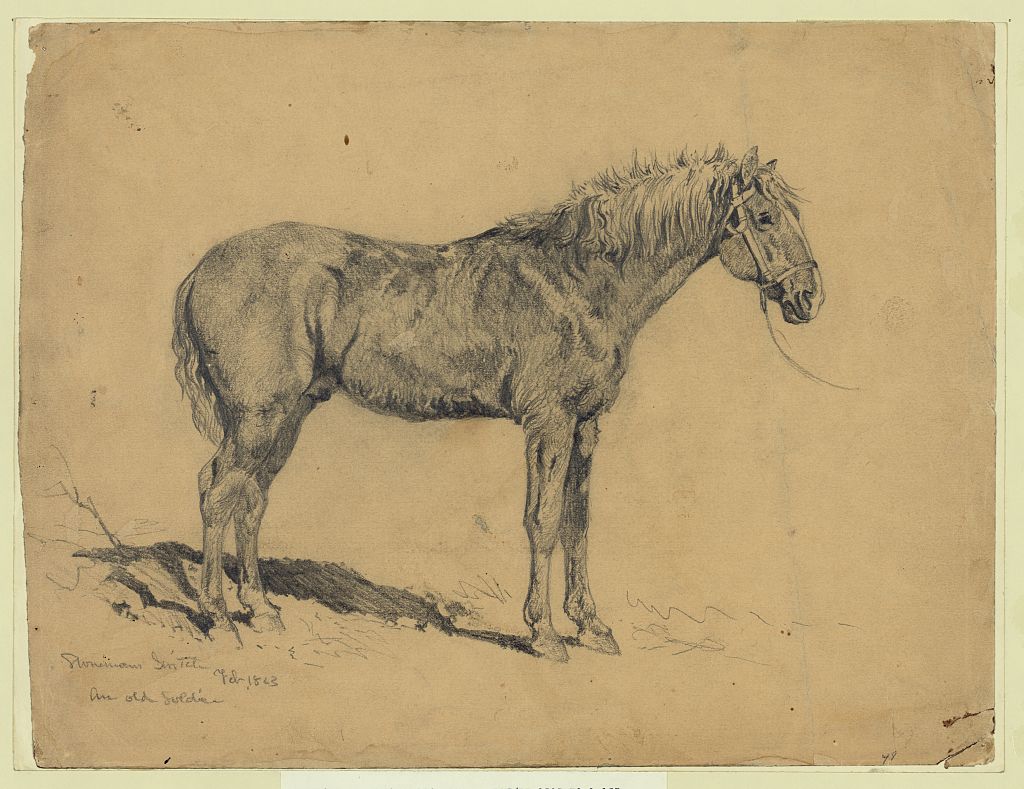

Sketch by Edwin Forbes, February 1863

Fodder shortages, particularly during winter months when army equines could not graze, limited their ability to perform needed tasks.

(Library of Congress)

According to the accounting of Brig. Gen. Rufus Ingalls, who served as Chief Quartermaster for the Army of the Potomac, when Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside assumed command of the army on November 9, 1862, it contained 3,911 army wagons and 907 ambulances. Added to those conveyances were 7,139 artillery horses, 9,582 cavalry horses, 8,693 team horses, and 12,483 mules, totaling 37,897 animals. The task of providing logistics for an army becomes even more impressive when one considers that all of those animals that provided the raw power to move it had to be fed. Army regulations stipulated that cavalry horses were supposed to receive ten pounds of hay and 14 pounds of grain per day. Artillery horses and wagon-pulling mules probably needed even more intake due to the amounts of energy they expended in their work. During late fall and winter campaigns, equines were not able to graze to supplement ration shortfalls, so not only did animals transport supplies for the army’s soldiers, but some also had to transport food for themselves, a factor that students of the Civil War do not often consider.

However, by December 5, 1862, some regiments were still lacking important supplies. For example, the 2nd Michigan Infantry’s Capt. Charles Haydon, encamped with his comrades in Stafford County, waited for orders to cross the Rappahannock and engage the gathering enemy. He killed some time by writing in his journal noting the weather and condition of the men: “Snow commenced to fall at noon & still (bedtime) continues rapidly. It looks rather dismal. The mud is already deep. The men are ragged & short of shoes & have only shelter tents which are in fact more like a dog kennel than a habitation for men.” Haydon added that their shelter tents were fine for field service, but “very insufficient protection against a severe winter storm.”

Artillery commander Charles Wainwright wrote in his journal on December 7 about the lack of foraging opportunities in Stafford County. “With us not a thing is to be had in the country; on the contrary, hosts of half-starved inhabitants look to our commissary for food and to keep them alive,” Wainwright noted. As a means of self-care, soldiers foraged from the countryside. Although, with an army of over 100,000 men and tens of thousands of animals, it did not take long to deplete most of the available local resources.

With the short railroad line fully operational, supply shortages for the Army of the Potomac largely eased for the rest of the campaign.

The important supply lines of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad and the Virginia Central Railroad are visible on this map produced later in the war.

(Library of Congress)

Despite the Army of Northern Virginia maintaining control of its primary supply lines to centers of production and distribution—namely the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac railroad south of Fredericksburg, and the Virginia Central Railroad to Richmond and points south and west—the army’s active late summer and fall campaigning took a toll on its quartermaster and commissary supplies.

While trying to figure out the intentions of the Army of the Potomac, Gen. Robert E. Lee wrote to the soon-departing Secretary of War George Randolph on November 17, expressing supply concerns. Lee opened on a cheery note by telling Randolph that he was “glad to learn of your purpose to send to Texas to purchase horses for the cavalry.” However, the army commander quickly pivoted to his point for writing: “The future supply of subsistence for the army is to me a source of great anxiety. I have endeavored all in my power to economize that that now exists, and to provide for our future wants.” Lee followed by explaining that he had increased the ration amounts because the men were not receiving anything other than bread and meat. He noted that the situation was still the same: “The daily diet of the men is bread and meat, without any addition of vegetables, &c. and, in view of the labor before them, I do not think it can be reduced to advantage.” Other supplies were lacking, too. Lee told Randolph that over the last few days the army had received “about 5,000 pairs of shoes, and clothing and blankets in proportion,” which had certainly helped, but he still had “about 2,000 men barefooted, and about 3,000 more whose shoes are in such a condition that they will not last longer than another march.”

Food was still on Lee’s mind the following day when he wrote to Gen. Samuel Cooper in Richmond to inform him “that much subsistence can be procured in the counties of Culpeper, Madison, and Greene, if prompt measures are at once taken to collect them.” Lee explained that a cursory examination showed that there were 67,857 bushels of wheat and 290,500 pounds of pork in those three counties alone.

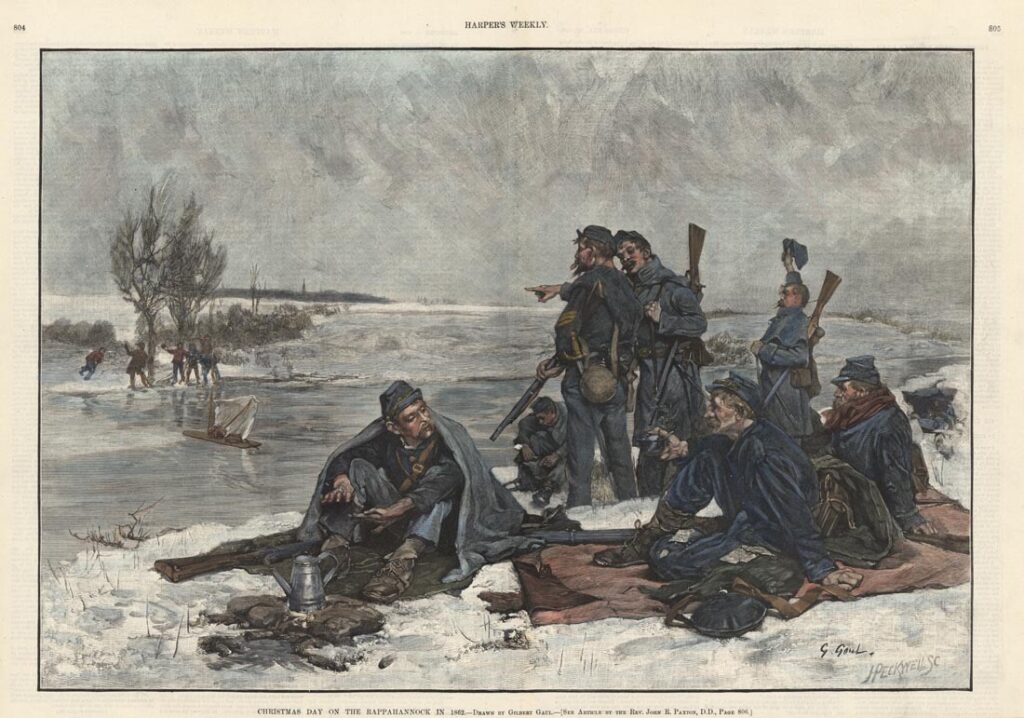

Drawn by Gilbert Gaul

Some soldiers on both sides alieviated supply shortages by trading the the enemy for things they needed.

(Harper’s Weekly, December 11, 1886)

Among some of the earliest Union troops to arrive across from Fredericksburg were some Second Corps units. They found that one way to relieve supply issues and obtain hard to get items—particularly those not issued by the army—was to trade with the enemy. Posted upstream from Falmouth, Pvt. Eugene A. Cory and his 4th New York Infantry quickly understood that well-supplied units could benefit themselves greatly. Cory explained, “Two [enemy soldiers] generally came over at a time, and as soon as they arrived barter would commence, and in a few minutes the tobacco would be exchanged for overcoats, shoes, blankets, coffee and sugar, or any of the numerous articles plentiful with us, but scarce with them . . . both parties being satisfied with their bargains. . . .” Unfortunately for the Confederates, only a small number of their soldiers benefitted in this manner.

As the portions of Lee’s army started concentrating toward Fredericksburg, orders included notes like that sent to Brig. Gen. William Nelson Pendleton: “The general [Lee] wishes every arrangement made to secure forage on the road for your animals, a quartermaster preceding the command, or and agent [to pay].

While the Confederates seemed to have experienced many ebbs and flows in properly supplying food, equipment, and camp materiel to its soldiers throughout the war, it appears that after the summer of 1862, they almost always had plenty of munitions and weapons on hand. Some of that came from captures made on earlier victorious battlefields. On Dec. 8, Richmond War Department clerk John B. Jones noted in his personal diary receiving communication from Lee about the narrowing gap between Union artillery and that of the Confederates, mostly due to captures but also recommending outdated cannon tubes be recast into more effective guns.

(Public Domain)

The carnage on the battlefield, combined with the Federal retreat back across the Rappahannock, provided Confederate soldiers with numerous opportunities to scavenge the Union dead for needed supplies. Shoes, uniform parts, blankets, rubber blankets, canteens, haversacks, shelter halves, knapsacks, and just about anything else was fair game. In addition, the Confederate army picked up thousands of shoulder weapons to repair, refurbish, and reissue. (For more on this aspect soldier battlefield supply see our previous History Wire posts, A Man Could Have Got Almost Anything He Wanted: Soldier Pickups on Central Virgina’s Battlefields, Part I and Part II.)

In the aftermath of Fredericksburg, and with the capture of even more Union supplies, the Army of Northern Virginia was still struggling to meet many soldiers’ needs. With it being wintertime, they felt the shortages keenly. Pvt. Alva Benjamin Spencer, 3rd Georgia Infantry, wrote from “Camp near Fredericksburg” about his regiment’s lack of tents. Spencer explained, “We are still without tents. The Government has furnished each company with one tent for the officers. The privates must do the best they can. Some have small tents captured from the enemy, in which they sleep quite comfortably. It has been said by some that a soldier needed only what he could carry; this is a mistake. A soldier in this climate needs much more than he is able to carry on his person. If one gets himself along without any baggage, he does well.”

The shortages went for food as well. Lee wrote to Seddon on January 23, 1863, about the necessary reduced rations, explaining that the salt and meat rations were reduced with sugar to be substituted. However, Lee noted, “There is no sugar here for the purpose, and the salt meat is very low; in consequence, the men are on short rations at a very bad time. Can it be remedied?” A couple of weeks later in a diplomatically worded but obviously pointed letter to Secretary of War James Seddon—who took over for George Randoph in November 1862—Lee explained he had expended all of his available resources attempting to gather food in counties south and west of the Fredericksburg area. Seddon forwarded Lee’s memo to Commissary-General of Subsistence Gen. Lucius Northrop. Northrop responded that following the Battle of Fredericksburg, and as “soon as it seemed settled that no father advance of the enemy was to be expected, all the meat available for this army was ordered from Atlanta, on the 15th and 16th [of December].” Unreliable railroad transportation appeared to largely be the problem. Whatever the fault, the result was a shortage that sapped the morale of many soldiers, especially those who had been conscripted.

The Chancellorsville Campaign

Gen. Hooker instituted several measures, including some involving supply, that helped revive the morale of the Army of the Potomac heading into the Chancellorsville Campaign.

(Library of Congress)

In response to a series of questions posed by Montgomery Meigs, Quartermaster-General of the U.S. Army, about supply issues following the Chancellorsville Campaign, Rufus Ingalls, who was Chief Quartermaster for the Army of the Potomac noted, “No wagons followed the main column over the river at first. Some ammunition wagons were brought up, but not necessarily.” Ingalls noted that “Pack-mules were used to transport reserve ammunition, and to pack up other supplies from the wagon parks.” Ingalls went on to explain the loads each mule could carry. “A 6-mule wagon will carry 1,400 short rations of provisions . . . and eight days’ rations of short forage for the 6 mules, or 25 boxes of small-arms ammunition. A good pack-mule could carry 2 boxes small-arms ammunition, and six days’ of oats for himself, or an equivalent in weight of subsistence for men.” As historian Earl Hess notes, while pack mules obviously could not carry as much as a wagon, they could avoid roads that swamped wagons and they did not create major marching obstacles for infantry as wagons did.

One reason supply wagons were not as necessary for the campaign was that Federal soldiers were carrying so much themselves. In preparation for the campaign, the United States Military Railroad (USMRR) stockpiled boxes of hard bread and barrels of salt pork for issue and consumption by Union soldiers. Pennsylvania soldier, Charles Hunter, writing home to family in Philadelphia commented on April 20, 1863, that, “We have 8 days of rations to carry with us when we do go and every man has to carry that much.” Army rations typically consisted of about 9 or 10 hardtack crackers and almost a pound of salted pork per day per soldier. “So you can form some idea what a load, we will have 80 crackers, that is 10 a day,” Hunter noted. Hunter also explained he would get “3 lbs. of fat pork for 3 days.” To fill out the other days’ meat rations, he stated that “the cattle will follow us up for the other 5 days for our fresh beef.” To feed over 100,000 mouths for eight days obviously necessitated a lot of food. Carrying their rations and other needed equipment required a level of endurance that taxed even the most seasoned soldiers, as Hunter clearly understood. “So what with 8 day rations and one [extra] shirt & drawers & woolen blanket & rubber blanket & half of a tent [shelter half] you can think it won’t be an easy load, and it won’t be much wonder if a great many men will have to drop out on the way.” Hunter was more prophetic than he knew.

Such loads ultimately created great waste, as soldiers unburdened themselves by tossing away items on the march, in battle, and during the retreat. Chief Quartermaster for the Second Corps, Lt. Col. Richard N. Batchelder, reported to Ingalls that “Since the return [from the campaign] 2,915 knapsacks, 2,084 haversacks, 2,373 blankets and 2,085 shelter-tents have been drawn, to supply the place of those lost and abandoned on the battlefield” for the First and Third Divisions of the corps. Some of the army’s other corps quartermasters provided astounding equipment losses as well.

In this photograph, boxes of hardtack and barrels of salt pork await distribution to the troops.

(Library of Congress)

On the Confederate side, Federal movements in North Carolina and southeast Virginia helped bring a bit of unintended relief to Lee’s hungry army in the Fredericksburg area. In mid-February 1863, Lee ordered Lt. Gen. James Longstreet to take charge of George Pickett’s and John Bell Hood’s divisions south of the Appomattox River in preparation to meet the Federals should they advance. The absence of Pickett’s and Hood’s men and their animals alleviated some of the burden of supply, but other shortages arose.

At the end of March, Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton wrote to Richmond requesting 1,200 horses for the army’s artillery. Nelson explained that the previous year’s campaigning had killed many of the equines. In addition, the lack of forage during the winter months had claimed or reduced others. And lastly, the transition to heavier, larger-caliber artillery pieces necessitated more horses.

In April, food was on Lee’s mind again. Anticipating the upcoming campaign, he wrote Seddon that while his men may be able to survive on their current reduced rations in camp situations, it “will certainly cause them to break down when called upon for exertion.” Lee pleaded that “The time has come when it is necessary the men should have full rations. Their health is failing, scurvy and typhus fever are making their appearance, and it is necessary for them to have a more generous diet.”

Rations were a concern for regimental commanders, too. On April 27, the 30th North Carolina’s Col. Francis Marion Parker wrote to his wife about previously advising her to reduce the rations of their enslaved people at home. “By this means you will be able to spare the government some bacon, and recollect to reserve enough to send me some occasionally, as opportunity may offer,” Parker explained. While noting he and his regiment were “living tolerably well,” he added, “But I tell you the rations of the men is short; ¼ lb. of bacon is a small allowance for a soldier, for an entire day; particularly as they get nothing else.”

Such scarcities, along with the absence of Pickett’s and Hood’s divisions, make the Army of Northern Virginia’s victory at Chancellorsville all the more impressive. Scores of individual Confederate soldiers mentioned picking up needed items (including food) that Federal soldiers had discarded to lighten their loads on the march, in the fighting, and during the retreat across the Rappahannock River that the southerners in turn put to good use.

Baldwin oversaw efforts to collect arms and equipment from the Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville battlefields for future use.

(Public Domain)

Lt. Col. Briscoe G. Baldwin, Chief of Ordnance for the Army of Northern Virginia, had the battlefield scavenged for Federal supplies. The haul from Chancellorsville proved impressive. Baldwin noted that 29,500 muskets and rifles were collected. He admitted that about 10,000 of those were “dropped by our men, leaving 19,500 captured.” Also included were 8,000 cartridge boxes, 4,000 cap pouches, 11,500 knapsacks, and 300,000 rounds of infantry ammunition. Brought off the battlefield, too, were 13 artillery pieces, nine caissons, three battery wagons, two forges, 1,500 rounds of artillery ammunition, and various harness, wheels, axles, and ammunition chests. Finally, Baldwin mentioned that “A large quantity of lead has been and is now being collected from the battle-fields.” These were probably dropped and fired bullets collected from the ground surface.

Still, with hunger being a persistent complaint when not consistently alleviated, it plagued Lee’s army following the battle, too. The 37th North Carolina’s Pvt. Thornton Sexton wrote to his family after Chancellorsville requesting a box of food from home. “I Can in form you that I have not had nothing to eat in two days an I am al Moost starved I want you Bring Mee a box of pervines [provisions] if you Can for times is hard hare now,” Sexton wrote. Before closing, Sexton reiterated his current situation: “Well i never node what bad times before in my life all my frends my best respets i gve them I hauve not received no mooney Sence I was at home i need somthing to eat Mity bad if i cood git it.”

Some of Lee’s staff officers were looking for food, too. Writing to his sister on May 8, 1863, Maj. Walter Taylor inquired of her perhaps more for variety than quantity. “Can Mr. Wilson get me anything to eat? Can a fish be had now & then? piece of fresh beef? butter? Vegetables &c. If you see a chance of getting anything, buy it for me. Thomas can always bring it up.” Thomas may have been one of the Taylor’s enslaved men. “We have peas, rice, & potatoes. Can we not get greens of some sort? I would like also to buy a jar or two of pickles, can they be had. Never mind the price,” Taylor pled.

While political considerations appear to be the primary motivation for Lee’s army to take the war into Pennsylvania in June, reliving central Virginia’s heavy burden of supply and the potential acquisition of supplies along the route and in the Keystone State were bonus incentives. Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s men captured Federal supplies at Winchester, and all three of Lee’s corps offered Maryland and Pennsylvania farmers and businesses vouchers for goods, or if necessary, impressed needed supplies.

Conclusion

This photograph shows a bee hive of activity at the Aquia Landing supply base. Note the wagons and equine teams at the left.

(Library of Congress)

Overall, much depended on effective and efficient army logistics. Although not always a determining factor in the success or failure of a specific battle or campaign, a consistent flow of supplies from centers of production and storage via reliable distribution networks played a large role in the grand scheme of the American Civil War. However, almost constant logistical challenges arose for both the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virigina during their central Virginia campaigns of 1862 and 1863.

Despite the Army of the Potomac having an abundance of materiel, issues like poor communication and the need to rebuild an infrastructure system that could meet their supply needs created moments of lost opportunities as well as periods of shortages during the Fredericksburg Campaign. Transportation and distribution issues plagued the Confederacy’s ability to effectively resupply the Army of Northern Virginia after the arduous campaigns during the summer and fall of 1862. Lee’s army was able to meet a measure of its needs through formal and informal battlefield scavenging, but systemic logistical issues continued to produce shortfalls. And while victory on the battlefield helped offset potentially demoralizing effects of supply shortages, the Army of Northern Virginia’s logistical troubles hovered high over it like a dark cloud.

Finally stabilizing its supply lines and increasing inflow after Hooker assumed command, a well-provided Army of the Potomac produced a tremendous amount of government waste during the Chancellorsville Campaign. Overburdened with rations and gear, much of it ended up on the battlefield and thus in Confederate hands as another retreat returned them to their Stafford County camps. In Lee’s army, the subtraction of two divisions to southeast Virginia should have brought some supply relief, but again, unreliable transportation networks and inconsistent delivery of food and equipment only added to his headache of fighting a campaign without all of his soldiers.

Sources and Suggested Additional Reading

Albert Z. Conner, Jr. with Chris Mackowski. Seizing Destiny: The Army of the Potomac’s “Valley Forge and the Civil War Winter that Saved the Union. Savas Beatie, 2016.

Richard D. Goff. Confederate Supply. Duke University Press, 1969.

Michael C. Hardy. Feeding Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Savas Beatie, 2025.

Edward Hagerman. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. Indiana University Press, 1988.

Earl J. Hess. Civil War Logistics: A Study of Military Transportation. Louisiana State University Press, 2017

Earl J. Hess. Civil War Supply and Strategy: Feeding Men and Moving Armies. Louisiana State University Press, 2020.

Parting Shot

Drawing by Winslow Homer

African American teamsters played an enormous but too often underappreciated role in the logistics of both the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia.

(Library of Congress)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.