by Julian Scott

This somewhat-oddly titled 1872 painting depicts the Vermont Brigade during the fighting withdrawal of the Sixth Corps on May 4, 1863.

(Public Domain)

Introduction

Few other brigades, Union or Confederate, sustained the number of casualties and encountered the trying situations that the Vermont Brigade suffered while fighting on the battlefields that the Central Virginia Battlefields Trust works to preserve.

The Green Mountain State men fought at Fredericksburg in December 1862, and at Second Fredericksburg during the Chancellorsville Campaign. In the late fall of 1863, they participated in the Mine Run Campaign. As explained below, the Vermont Brigade endured heavy fighting and high casualties at the Battle of the Wilderness. It was their most trying battlefield experience. At Spotsylvania Court House, the Vermont Brigade, had three regiments that participated in Col. Emory Upton’s May 10, 1864, attack. They also fought as part of the Sixth Corps assault at the Mule Shoe on May 12, battled again on May 18, and yet again on May 21.

(From Vermont in the Civil War: A History, Vol. 1 by George G. Benedict, 1886)

The Vermont Brigade formed in fall of 1861, under the charge of native son, William F. “Baldy” Smith. For the majority of the war the highly respected unit consisted of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th Vermont Infantry regiments. For a time in 1862 and 1863, the orphaned 26th New Jersey, a nine-month regiment, fought with the Vermonters, but by the summer of 1863, it was back to an all-Vermont unit. The 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery (also known as the 11th Vermont Infantry) joined the brigade during the fighting at Spotsylvania Court House and stayed with it through the end of the war.

By the time of the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Vermont Brigade had already earned a reputation for their combat prowess and toughness on the march. Their grit came partly through solid leadership and desperate trials by fire at Lee’s Mill and Williamsburg fighting as part of the Fourth Corps during the Peninsula Campaign, and at Savage’s Station in the Seven Days’ Battles after they transferred to the Sixth Corps. Seeing fighting at Crampton’s Gap along South Mountain on September 14, 1862, they were largely unengaged at Antietam three days later and fortunately missed the worst of that monumental battle.

The Battle of Fredericksburg

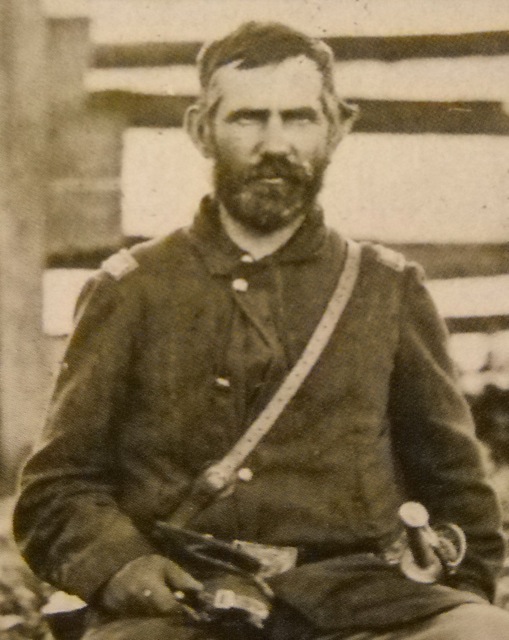

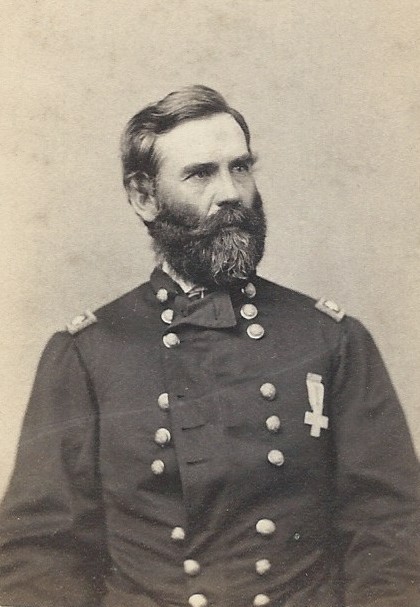

An 1840 graduate of West Point, Col. Whiting commanded the Vermont Brigade at Fredericksburg. Born in New York and living in Michigan at the beginning of the war, Whiting first commanded the 2nd Vermont Infantry.

(Find A Grave)

As one of the three brigades in the Second Division of the Sixth Corps, the Vermonters, then commanded by Col. Henry Whiting, found itself fighting on the south end of the Fredericksburg battlefield as part of Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s Left Grand Division. Maj. Gen. “Baldy” Smith commanded the Sixth Corps and Brig. Gen. Albion Howe headed their division.

Departing their camp near Belle Plain on December 10, the brigade marched to the Rappahannock River, finally crossing on December 12. While occupying an area situated between the river to the east and the Bowling Green Road (Richmond Stage Road) to the west and positioned between the plantation homes of Alfred and Arthur Bernard—The Bend to the north and Mannsfield to the south, respectively—the 6th Vermont ventured toward the road to drive back harassing Confederate skirmishers, pushing the southerners toward the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad across ground today largely occupied by the Shannon Airport campus and on the northern adjacent border of the Slaughter Pen Farm portion of the battlefield. The 4th Vermont relieved the 6th on the skirmish line later in the day.

On morning of December 13, Col. Whiting sent the 3rd and 5th Vermont regiments forward to bolster the right end of the forward brigades’ lines. After the morning fog cleared, Confederate artillery on high ground west of the railroad tracks, as well as further away on Howison Hill, began pounding away. To try to avoid being hit, the Vermonters and the 26th New Jersey were ordered to lay down. Despite this precautionary effort, they took some casualties.

(Tim Talbott)

Gen. Howe reported that soon after this, on the west side of the Bowling Green Road, “the enemy, with re-enforced line of skirmishers, attempted to drive back our skirmish line, but they immediately came in collision with those hardy veterans . . . of the Second Vermont, and were handsomely repulsed. . . .” Led by Lt. Col. Charles Joyce, the 2nd Vermont advanced just to the south of Deep Run and engaged in a heavy skirmish fight, many of the men exhausting their sixty rounds of ammunition. A soldier in Company D noted, “their we laid loading rapidly as possible during the afternoon . . . with shot and shell flying over our heads from the heights, from our guns to the rebels and from the enemy artillery to ours.” Lt. Chester Leach of the 2nd wrote, “we were put up to the front, skirmishing & a pretty hot time we had too.” The 2nd Vermont ended up suffering the most casualties in the brigade at Fredericksburg, the majority coming during this episode.

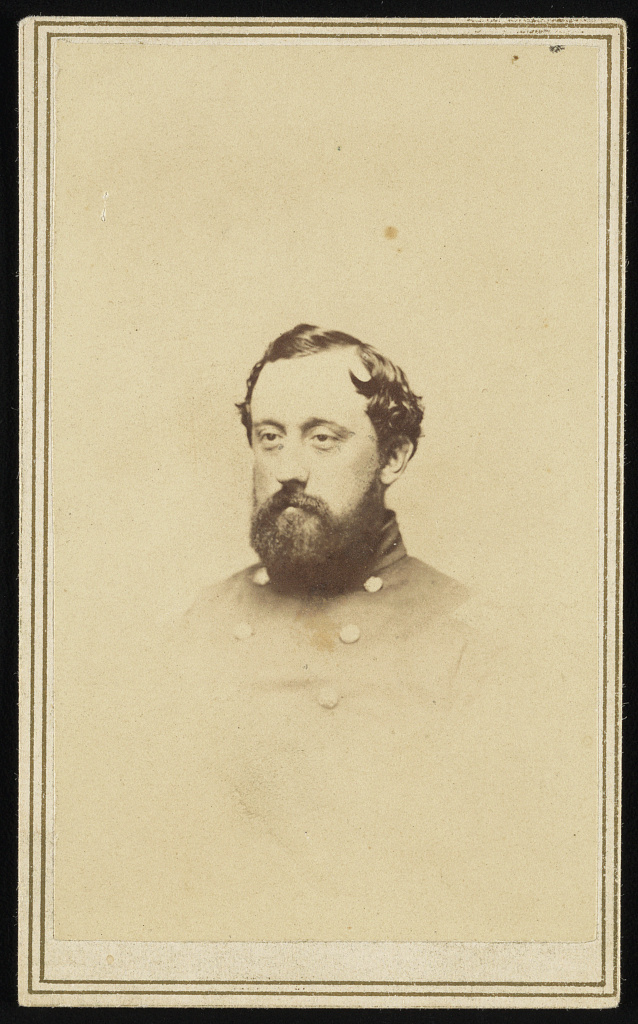

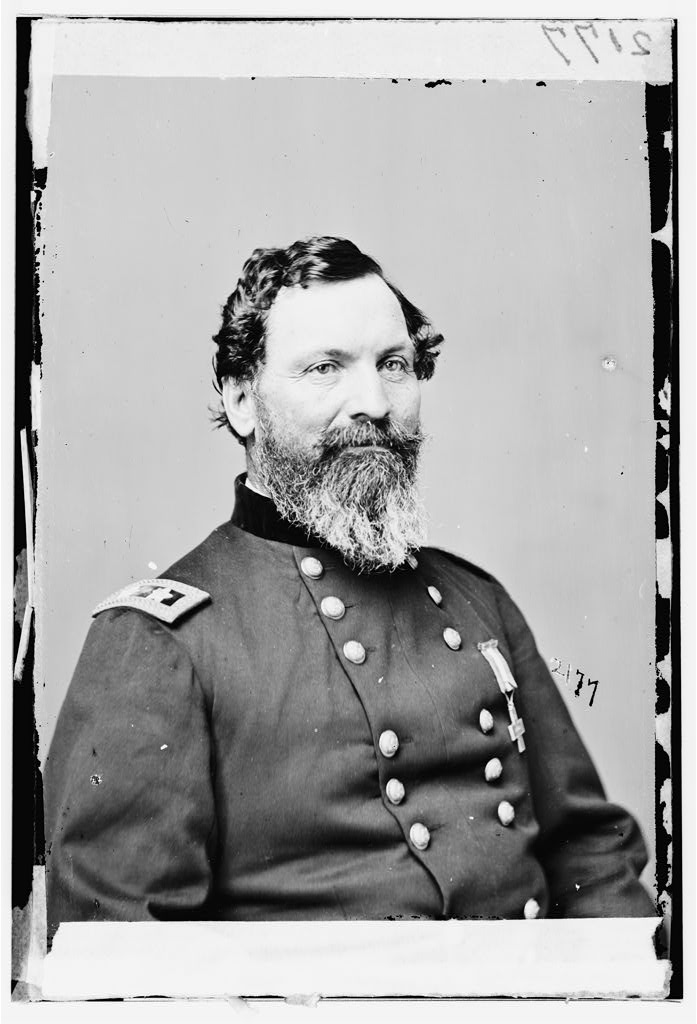

Lt. Col. Foster led the 4th Vermont Infantry on the skirmish line at the Battle of Fredericksburg. In February 1864, Foster became commander of the regiment. He was wounded in action at the Wilderness on May 5, 1864

(Library of Congress)

On the skirmish line to the left of the 2nd Vermont was the 4th Vermont, who linked with Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s division to its left. Lt. Col. George P. Foster led the regiment. Supporting Gibbon’s right flank, the 4th moved forward in an afternoon assault toward the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad tracks. Receiving rifle fire as well as blasts of artillery from Capt. Joseph Latimer’s and Capt. Greenlee Davidson’s Confederate batteries, the 4th Vermont received the second most casualties in the brigade. Lt. William Henry Martin wrote a brief letter home on December 15, explaining “We had a hard fight and lost fifty six men.” Martin added that his own company “lost eight, one shot dead and another lived a few hours.” “We held a strong skirmish line in an open field & was so exposed to the sharpshooters that we lost heavily,” Martin noted.

Some of the 4th Vermont soldiers mention crossing a ditch fence that divided parts of what would become known as the Slaughter Pen Farm. Sgt. William Stevens, watching Gibbon’s men from the reserve picket line wrote that “battalion after battalion marched in solid column, with colors waving, towards those woods, so full of death to them, the sight was grand.” Lt. Martin noted that they “advanced within ten rods [55 yards] of the enemy. We were in an open field without the least bit of shelter so were exposed to the deadly aim of the sharpshooters & lines of Rebil infantry. Evry few moments some of our Regt. would fall.” This was Martin’s first battle. He was amazed. “There one man fell shot dead by a miney through the forehead. Soon another one through the bowels . . . The shot flew like hail around us & we had to lye and take it,” Martin detailed. Without support, Gibbon’s three divisions withdrew. The 4th Vermont fell back, too.

(Library of Congress)

Later in the afternoon, the 3rd Vermont was ordered to the front as skirmishers. Using the ravine of Deep Run, and led by Lt. Col. Thomas Seaver, they got into position, mostly hidden by a slight rise of ground. An assault by Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert’s New Jersey Brigade was pushed back by Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s two North Carolina regiments, the 54th and 57th. Seaver’s Vermonters now drew the attention of the Tar Heels. Largely protected by the rise in ground, Seaver’s men waited until the North Carolinians were in close range and sent a volley. Of the fighting, a soldier in the 3rd wrote, “we jumped to our feet and gave them a withering volley which caused many of them to bite the dust.” The 3rd then moved forward, firing more volleys into the retreating North Carolinians, who withdrew to the railroad. Between their fight with the New Jersey Brigade and the 3rd Vermont, Law’s two regiments suffered over 170 casualties.

After missing most of the fighting on December 13, the 5th and 6th Vermont finally got a taste of the fighting on the skirmish line on December 14. Col. Lewis Grant’s 5th Vermont lost two men killed and eleven wounded. Col. Grant himself received a painful spent bullet wound.

Being on the skirmish line allowed some Vermont men to meet their foes face to face when a truce was called to tend to the wounded and bury the dead. A soldier in the 5th noted, “They said they would not fire if we would not—we agreed—Met them half way and shook hands with them and had a good talk. . . .”

On the evening of December 15, the Vermonters crossed the pontoon bridge back to Stafford County and eventually to their camps near Belle Plain.

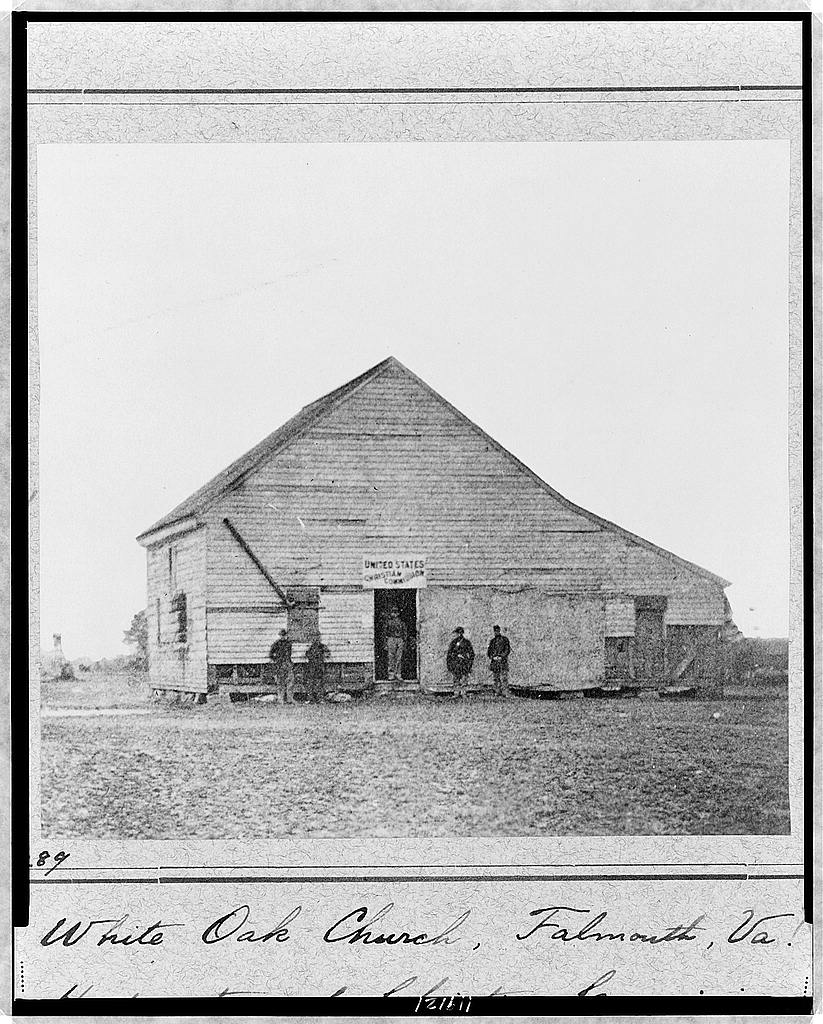

The Vermont Brigade spent much of the winter of 1862-63 encamped with the Sixth Corp in the vicinity of White Oak Church in Stafford County.

(Libray of Congress)

Spending much of the winter of 1862-63 near White Oak Church, the Vermont Brigade, along with the rest of the Army of the Potomac, underwent a transformation. After Gen. Burnside’s misfortune with the infamous “Mud March,” he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who instituted a number of measures that helped improve the morale of the army.

Although not a battlefield casualty, Col. Whiting, who had commanded the Vermont Brigade since mid-October 1862, resigned his commission on February 9, 1863. Unhappy about not being promoted, and conspicuously absent from much of the fighting at Fredericksburg, accusations of cowardice followed Whiting, who returned home to Minnesota. Following Whiting’s departure, Col. Lewis Addison Grant of the 5th Vermont became the brigade commander and led it through the remainder of the war. Additionally, the Sixth Corps had a new leader. Brig. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith was out, replaced by Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick.

The Chancellorsville Campaign

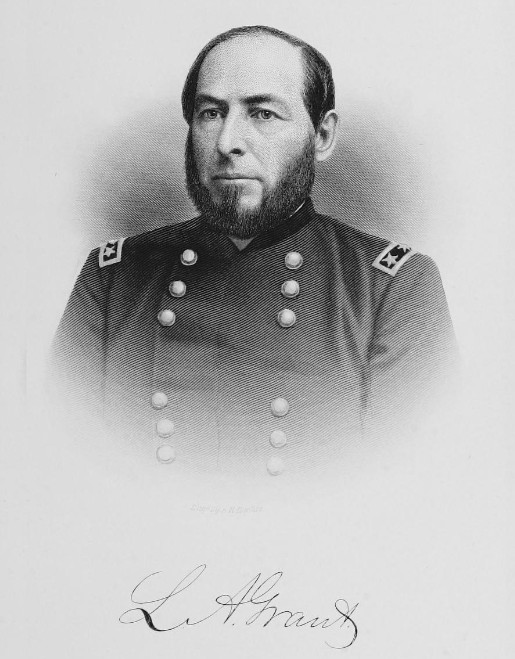

Col. Grant commanded the Vermont Brigade during the Chancellorsville Campaign. He received a promotion to brigadier general in April 1864 and led the brigade through the end of the war.

(Vermont in the Civil War: A History, Vol. 1 by George G. Bendict, 1886)

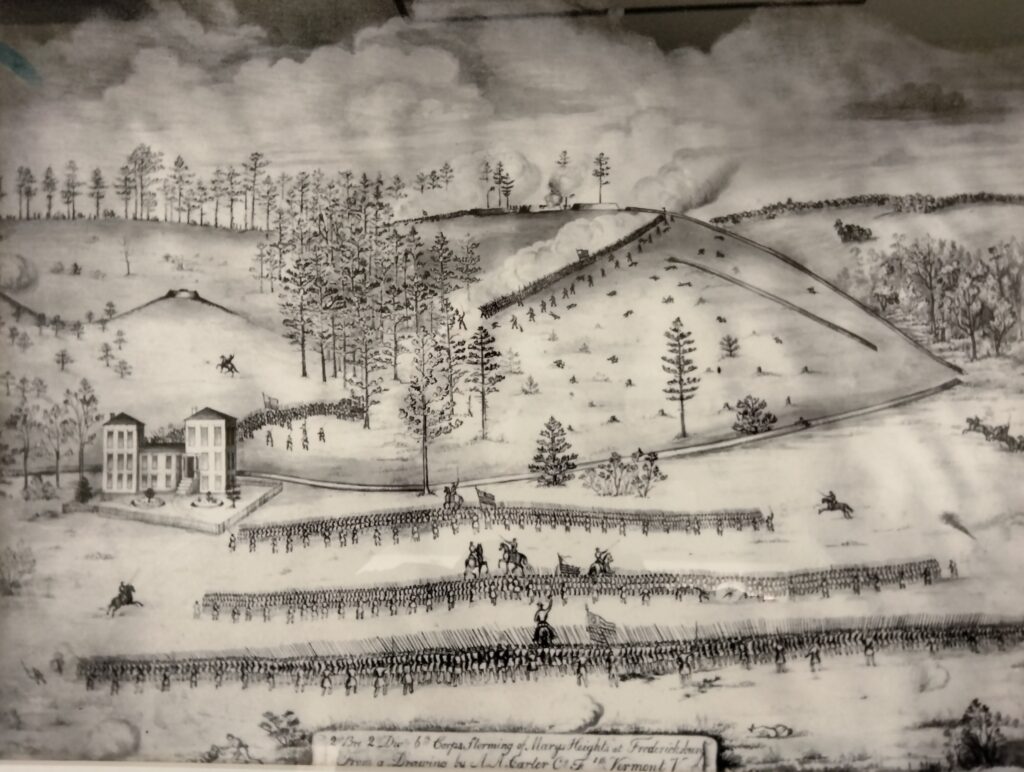

On April 28, the Sixth Corps received orders to cross the Rappahannock River south of Fredericksburg where they had in December to serve as a diversion of sorts while other corps marched on Chancellorsville in attempt to turn Lee’s left flank. The Sixth Corps was to then move west and come in on the rear of the Army of Northern Virginia who was then battling Hooker at Chancellorsville. Brig. Gen. Albion Howe’s division, including the Vermont Brigade, crossed the river on the evening of May 2.

To assault the heights west of Fredericksburg, Howe formed three “storming columns” on the morning of May 3. Two of the columns involved Vermont Brigade regiments led by Col. Grant, and Col. Thomas Seaver of the 3rd Vermont. The majority of both Grant’s and Seaver’s columns moved west to assault the Confederate defenders on Telegraph (Lee’s) Hill and Howison Hill. Much of this attack crossed the flat plain of ground where the CVBT office now sits. In 2022, CVBT helped save some of the nearby greenspace that the Vermonter’s marched over. Additionally, some of the 6th Vermont attacked the southern end of Marye’s Heights along with Brig. Gen. Thomas Neill’s column.

Among the attackers was Lt. Chester Leach of the 2nd Vermont. Writing to his wife six days later, Lt. Leach noted, “We advanced over the hill & soon came in range of a line of Infantry & it was rather hot work for awhile, & I began to think we would have to retreat but we held out till other regts came to our support & then the rebs had to give way. I never got into a place where the air was quite as full of lead as it was for a short time after we got on top of those heights, & it almost seems a wonder how so many remained unhurt. . . .”

Leach’s 2nd Vermont comrade, Pvt. Wilbur Fisk, noted that “This was the sharpest fire our regiment has been under. The men fell fast on right and left.” He shared several close calls that his comrades experienced during the fighting: “Bullets play curious freaks sometimes, and every battle has its hair-breadth escapes. One fellow had had his gun shot out of his hands, and another close by had his life spared because his gun intercepted the bullet. Sergt. [Martin] Davis of Company E, was struck in the breast with a ball, but an account book in his pocket was his life-preserver. Capt. [Erastus] Ballou, Company [K], had the skin scratched off his nose by a rebel minnie, and that is shooting a man almost within an inch of his life. I might multiply incidents like these to an almost endless extent.” The 2nd received praise from Col. Grant in his report when he noted the regiment, “covered itself in glory.”

The 3rd Vermont and the part of the 6th Vermont in Seaver’s column also provided additional force to push Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippians out of their strong positions on the south side of Hazel Run.

In the May 3 fighting, Col. Grant reported his brigade lost “15 killed and 144 wounded, including 4 commissioned officers, and 3 missing; in all 162” casualties.

Pvt. Fisk often wrote letters to the Montpelier Green Mountain Freeman newspaper, providing an important chronicle for his regiment and the Vermont Brigade.

(Find A Grave)

The May 3 fighting for the Sixth Corps was not over. More combat waited to the west at Salem Church for Sedgwick’s other divisions. Although the Vermont Brigade missed additional action on May 3, they were thrown into a desperate engagement on May 4.

During the late afternoon, as the Vermonters fought North Carolinians and Louisiana troops from Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division near Smith Run (a property that CVBT helped preserve), Sgt. Robert Coffey of the 4th Vermont performed several daring acts that eventually resulted in his receiving the Medal of Honor. In one instance, Coffey instructed a rebel officer to surrender and when the southerner swung his sword at Coffey, he blocked it with his Enfield rifle’s bayonet. Then when the officer pointed his revolver at Coffey, the Vermonter shot the Confederate. A few minutes later Coffey was able to capture at least two Confederate officers and five enlisted men by himself. When one of the Confederate officers noticed Coffey was briefly alone, he hinted to the other officer to turn the tables and capture Coffey, but the sergeant heard the talk and cocked his rifle’s hammer and told them to “march on.” Sgt. Coffey eventually turned the prisoners over to the provost guard for processing.

As the Sixth Corps and the Vermont Brigade continued its fight during its withdrawal toward the Rappahannock River at Banks’ Ford it met with repeated Confederate assaults. Corp. William Stowe of the 2nd Vermont wrote soon after the fight: “the line of battle in front of us was cut to pieces and our brigade constituted the rear line. the rebels came on at a charge bayonet expecting to take us all prisoners but they got mistaken in their plans when they ran against our brigade. their lines came so near us that I could almost hit them [by swinging] my gun. the Colonel of one of their regiments was killed within five rods of our regiment so you can see that they got close together before they run. their dead covered the ground as grey as a badger in front of us.”

Crossing the river early on the morning of May 5, the Vermonters returned to their Stafford County camps. Col. Grant commended his brigade in his reports: “The conduct of the troops was excellent. Too much praise cannot be awarded to the officers and men for their steady, brave, and gallant conduct.”

Following the Chancellorsville Campaign, the Vermont Brigade saw virtually no action at Gettysburg but then served as draft riot control in New York City and surrounding areas before returning to Virginia.

The Vermont expereinced fierce combat with North Carolina and Louisiana troops on May 4 near Smith Run, a property that CVBT helped preserve in 2001.

(Tim Talbott)

The Mine Run Campaign

The Vermont Brigade had limited roles in the fighting at Rappahannock Station on November 7, 1863. The 5th Vermont served as skirmishers, but most of the other units remained in a concealed and protected position, thus the brigade only had four casualties.

Later in the month, Col. Grant’ brigade embarked on the Mine Run Campaign with its Sixth Corps comrades. Crossing the Rapidan River on November 26 at Jacob’s Ford, the Sixth Corps followed the Third Corps as it moved south. When the Third Corps clashed with Confederates at Payne’s Farm, Gen, Sedgewick “immediately moved forward two divisions . . . and as the engagement progressed, advanced [Col. Peter] Ellmaker’s brigade upon the right and [Col. Thomas] Neill’s and [Col. Emory] Upton’s brigades upon the left to support General [William] French’s line. . . .” However, the Vermonters were held in reserve along with Brig. Gen. Torbert’s brigade and did not see action. For Pvt. Fisk of the 2nd Vermont, the battle was only auditory. He wrote, “We could not see the fight, for the wood was so dense that we could only see but a few rods ahead of us. . . .”

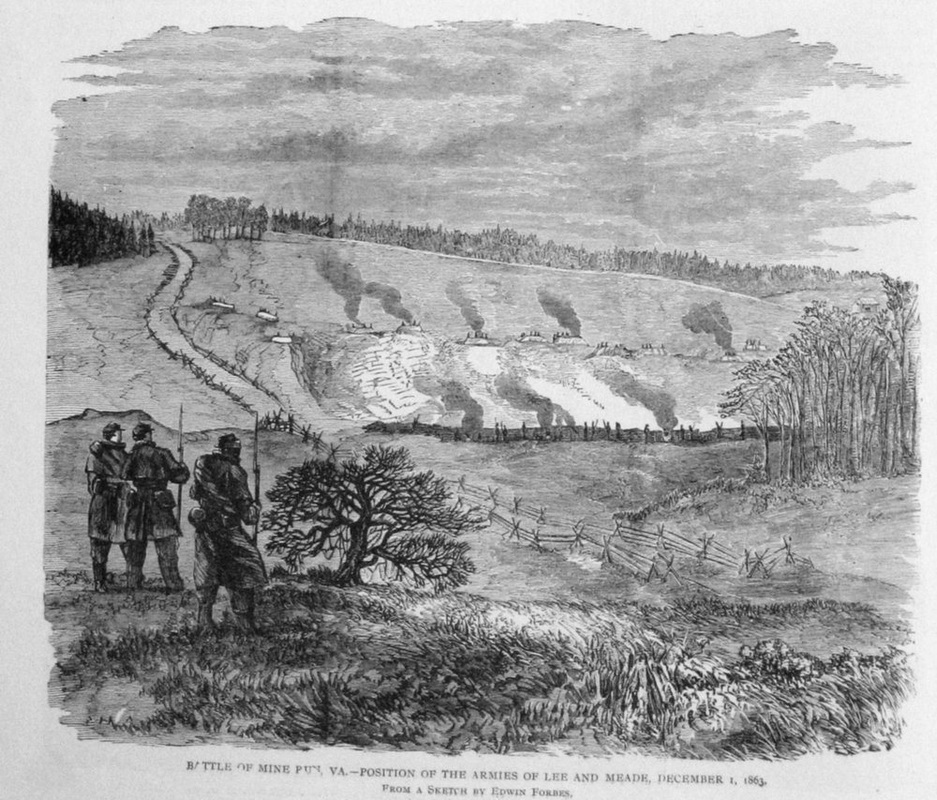

Woodcut image sketched by Edwin Forbes

In their correspondence home, several Vermont Brigade soldiers mentioned the extremely cold weather and strong fortified postions of the Confederates along Mine Run.

(Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper)

The 2nd Vermont’s Lt. William Henry Martin wrote home about the anticipated attack on the Confederate fortifications on the west side of Mine Run on the morning of November 30. “[We] were marched into a piece of woods on the enemies extreme left flank to attack at break of day. A surprise moovement. The 5th & 6th Corps were massed. The choicest troops of the army. It was a desperate moove, & the very best troops were choosen. The Vermont Brigade was to lead the attack,” Martin penned. However, as daylight broke, it was clear the position was too formidable to assault without heavy loss and no assurance of success. “It was then decided not to attack,” Martin wrote. Without fires, the cold cut the soldiers. “We never suffered so much before. I was never so badly chilled before. The nights are extremely cold,” Martin explained.

With Meade’s late fall campaign spoiled, the Army of the Potomac had few other alternatives than to recross the Rapidan River and return to their Culpeper County encampments.

During the winter of 1863-64, the Vermont brigade lost a number of its soldiers who received commissions in United States Colored Troops regiments.

The Battle of the Wilderness

At the Battle of the Wilderness, Gen. George Getty’s division, including the Vermont Brigade, served detached from the Sixth Corps.

(Find A Grave)

After several months spent in their Culpeper County winter quarters, all was hustle and bustle on May 4, 1864, as the Vermont Brigade broke camp and headed off on another campaign, this time under a new overall commander, Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant.

Upon receiving orders to march for what would become the Overland Campaign, Lt. Chester Leach, 2nd Vermont Infantry, wrote to his wife. “One year ago today, we were engaged at Fredericksburg Heights [Second Fredericksburg], since that time our regt has seen but little fighting although we were in a number of skirmishes & a few men were killed & wounded. Hoping for the best I bid you Good Bye,” Leach penned.

In what would be his last letter home on May 3, 1864, Lt. William H. Martin, 4th Vermont Infantry, hoped that the company’s captain would be back in time to lead it but explained, “I have got the unpleasant job of commanding the Company.” Most soldiers believed the spring 1864 campaign was going to be difficult, Martin among them: “We expect to see trying times when we march . . . Still we hope for success,” he wrote. With all the confusion of breaking camp, Martin explained, “my haste compels me to close without finishing my sheet.” A final line expressed a simple but heartfelt request, “Pray for your children in the Army.” Henry’s older brother Francis served in the 2nd Vermont Infantry. During the first day’s fighting in the Wilderness, Henry received a chest wound. Evacuated to a field hospital, he succumbed on May 8, 1864.

Detached from the Sixth Corps, the Vermont Brigade and the other two brigades from Maj. Gen. George Washington Getty’s Division, stopped briefly at Wilderness Tavern, but received orders to quickly move forward to the intersection of Orange Plank Road and Brock Road. There the Vermonters saw Confederate infantry brigades moving in their direction pushing the Federal cavalry. Fighting in the dense woods, artillery was limited to the roadway. Some of the Federal infantry started building improvised breastworks. But the Vermonters soon received an order to attack.

(Tim Talbott)

Moving forward in battleline, the landscape made communication difficult. Recently minted Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Grant, commanding the Vermont Brigade, noted in his official report that, “The ground was covered with brush and small timber so dense that it was impossible for an officer at any point of the line to see any other point several yards distant.” The Vermonters would fire volleys and then “hugged the ground as closely as possible, and kept up a rapid fire; the enemy did the same,” Grant reported. It was as if lead was flying from smoke shrouded trees fired by ghosts instead of from Confederate rifles. The Vermonters started falling by scores.

Gen. Grant tried to dislodge the Confederates, “but the moment our men rose to advance the rapid and constant fire of musketry cut them down with such slaughter that it was found impracticable to do more than maintain our then present position,” he explained. They held firm. After receiving support from three Second Corps regiments, Grant, noting a potential weakness in the Confederate line, asked the 5th Vermont to try to break it. Their major responded, “I think we can.” The line went forward and was partly successful, but the support troops “were thrown into some confusion” and went to the ground. The 5th Vermont outpaced its help and soon had to hit the dirt, too. With its ammunition nearly exhausted units from the Second Corps relived the Vermonters, who retired to their previous Brock Road position, when darkness mercifully halted the fighting. The Vermonters had fought for about five hours.

(Tim Talbott)

Getty’s brigades, and particularly the Vermont men, had helped plug the gap A. P. Hill’s Confederates were making and then held it until the Second Corps was able to get into position. However, it was at fearful cost. Grant explained that “One thousand brave officers and men of the Vermont Brigade fell on that bloody field. Was the result commensurate to the sacrifice? Whether it was or not the battle once commenced had to be fought.” Whether or not the Second Corps had been able to hold its own, “the enemy would have secured the important position and completely cut off that corps from the rest of the army,” if the Vermonters had not acted Grant noted.

May 6 brought additional combat for the Vermont Brigade as it attacked along with the Second Corps and successfully pushed A. P. Hill’s Confederates out of their improvised earthworks. However, James Longstreet’s Corps arrived on scene in the nick of time and counterattacked, forcing the Federals back toward Hill’s old position now occupied by Grant’s Vermont men. The brigade commander noted, “Perhaps the valor of Vermont troops and the steadiness and unbroken front of those noble regiments were never more signally displayed.” Taking tremendous casualties again, fortunately, reorganized Second Corps reinforcements arrived to relieve the pressure.

Carpenter began his service as a 21-year old second lieutenant in Company G when he enlisted on August 19, 1861. It ened with his death at the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5, 1864.

(Library of Congress)

Among those who received the Medal of Honor for courageous actions during the Battle of the Wilderness was Canadian-born 1st Sgt. Carlos H. Rich, 4th Vermont Infantry. Sgt. Rich, only 19 years old when he enlisted in 1861, and originally assigned the rank of corporal, received additional promotions to sergeant and first sergeant. Rich re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer in February 1864. During the May 5, 1864, fighting at the Wilderness, Rich noticed that his company’s first lieutenant, Edward Carter, was wounded. With the help of Carter’s brother Albert, they carried the lieutenant to safety while under fire. The following day, May 6, 1st Sgt. Rich received a wound to the thigh. Admitted to Emory hospital on May 11, 1864, Rich returned to his regiment in September after healing.

According to one historian’s count, the Battle of the Wilderness cost the Vermont Brigade 1,234 casualties, almost half of its men.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

Beloved by the Sixth Corps and the Vermont Brigade, Gen. Sedgwick was killed on May 9, 1864, at Spotsylvania. Sedgwick’s replacement, Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright commanded the corps through the end of the war.

(Library of Congress)

On the march from the Wilderness toward Spotsylvania Court House on May 7-8, 1864, the Sixth Corps route took them east along the Orange Turnpike to Chancellorsville and then to the Orange Plank Road (modern Old Plank Road). They then turned right on Catharpin Road at the Alrich Farm, a tract that CVBT is currently working to preserve for its role in fighting between the 23rd USCT and Gen. Thomas Rosser’s cavalry on May 15, 1864. During the move, the Vermont Brigade served as the rear guard, protecting the Sixth Corps wagon supply train.

Marching this route allowed the Sixth Corps to come in on the left of the Fifth Corps, who were the first to see action at Spotsylvania on the morning of May 8. While guarding the wagons the Vermonters became separated from their corps, but that evening they were ordered up to the leftward-extending line and received orders to move to the far left of the corps in an effort to outflank the enemy. Despite the challenging terrain and darkness, they finally found a suitable position and the following day the brigade’s soldiers constructed earthworks and exchanged shots with Confederates who had also extended their lines. May 9 also witnessed the death of Gen. Sedgwick, who was killed on the right end of the Sixth Corps line.

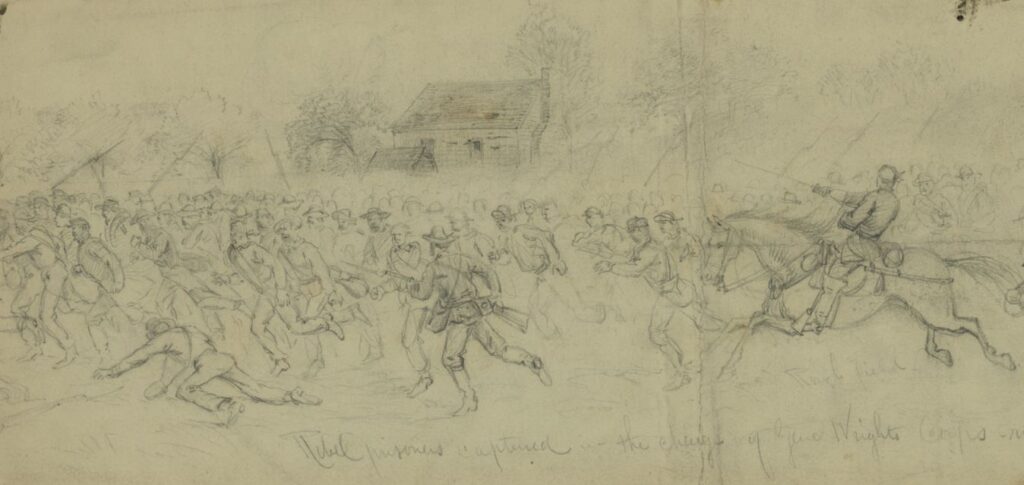

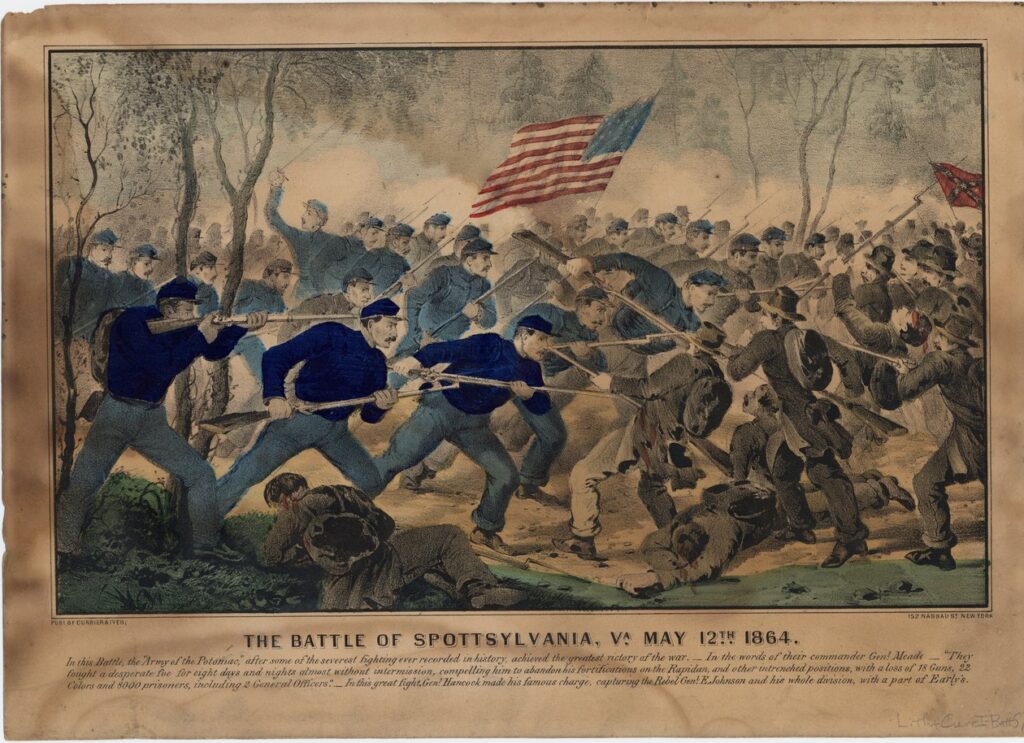

This sketch by Alfred Waud shows the prisoners netted by Col. Emory Upton’s assault on May 10, 1864, being sent to the Federal rear. While Upton’s twelve regiments captured about 1,000 prisoners, they lost a similar number in casualties.

(Library of Congress)

On May 10, Gen. Lewis Grant received orders to send three of his Vermont regiments to participate in an attack to be led by Col. Emory Upton against the Confederate line. Grant chose the 2nd, 5th, and 6th Vermont regiments. The three Vermont units composed the final line in the assault column. Although initially successful, and capturing about 1,000 prisoners, without proper support Confederate reinforcements arrived and drove out the attackers. About the fight, Pvt. Fisk of the 2nd Vermont wrote, “At the signal the three lines sprang to their feet, and rushed across the field, determined to drive the enemy or die. We followed immediately after. The rebels mowed down the men with awful effect. . . .” Grant reported that “The Vermont regiments . . . advanced, and under a galling fire, occupied the rebel works, while the other regiments . . . fell back. Orders were given for all to fall back, but it failed to reach a portion of the Second [Vermont], and some from each of the others, who remained in the works obstinately holding them against all attacks of the enemy until late in the evening, refusing to fall back until they received positive orders to do so.”

Born in Ireland, William Cunningham was 24 years old when he enlisted on September 5, 1861, as a private in the regiment’s Company D. His service records note that he was killed on the picket line on May 10, 1864.

(Library of Congress)

The Vermont Brigade reoccupied their previous position on May 11. While skirmish firing occupied most of the day, that evening the brigade received orders to form in the rear of the Sixth Corps.

The following morning, May 12, the Vermonters moved closer to the Second Corps’ right flank. After the assaults by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s divisions, Gen. Grant received orders to move to the Second Corps’ far left in order to relieve Maj. Gen. Francis Barlow’s division. After forming and sending out skirmishers, the Vermont men started digging in. Meanwhile, it was devolving into a slugfest along the Muleshoe salient’s northwest side back where they started from. Gen. Hancock ordered Grant to take some of the brigade and support the effort there with Hancock’s promise to send the remainder as quickly as possible. Unable to do much with his small force Grant was relieved to soon see his other regiments arrive.

Grant noted the ferocious nature of the fighting at the Angle. “It was emphatically a hand-to-hand fight. Scores were shot down within a few feet of the death-dealing muskets. A breast-work of logs and earth separated the combatants. Our men would reach over . . . and discharge their muskets in the very face of the enemy. Some men clubbed their muskets and in some instances used clubs and rails,” Grant reported.

They held the position, but as Grant noted, “The sight the next day was repulsive and sickening indeed.” Behind the works “the rebel dead were found piled upon each other. Some of the wounded were almost entirely buried by the dead bodies of their companions that had fallen upon them.” On the night of May 12, the Vermont Brigade moved to a new position on the far right.

Currier and Ives

(Pubic Domain)

Capt. Dayton P. Clarke of the 2nd Vermont Infantry eventually received a Medal of Honor for his fighting on May 12, 1864. His citation reads: “Distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand fight while commanding the regiment.” Another of the 2nd Vermont’s fortunate survivors, Lt. Chester Leach, wrote home to his wife on May 13, 1864, detailing the regiment and his company’s losses: “We have but five or six Officers left out of over twenty when we left camp. Col. killed, Lt. Col wounded, one Capt killed, Capt Bixby Co. E, only one Capt left with the regt. We were in a fight nearly all day yesterday & I don’t know what the loss of our Co[mpany] was yet for they were mixed up with other troops, & when we were relived by other troops I could not get together but six, & now I have but 4 privates, all told. . . .” Leach ended his letter by penning, “I will say Good Bye for the present trusting that I will have another opportunity [to write].”

From May 13 to May 17, the Vermont Brigade participated in several moves but saw little fighting. On May 15 they received a new regiment, the 11th Vermont, a huge unit consisting of 1,500 men also known as the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery.

On May 18, the Vermont Brigade with the Sixth Corps, and the Second Corps, made an assault over much of the same ground as the attacks of May 12. Brig. Gen. Grant noted that “Our loss, though not so heavy as in other engagements, was considerable, principally from artillery.” More maneuvering on May 19 brought a repose of sorts for the Vermonters until May 21 when the Confederates temporarily broke their skirmish line, but responding quickly, the Third Vermont was able to restore it before joining the rest of the Army of the Potomac as it marched southward to the North Anna River and more fighting beyond.

Conclusion

As an important part of the Sixth Corps, the Vermont Brigade went on to earn additional laurels at Cold Harbor, Petersburg, in the Shenandoah Valley, and back at Petersburg, where on April 2, 1865, they led the Sixth Corps assault that broke the Confederate defensive line on April 2, 1865, which precipitated the evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond and Lee’s surrender at Appomattox a week later.

Sources and Suggested Additional Reading

Howard Coffin. The Battered Stars: One State’s Ordeal during Grant’s Overland Campaign. The Countryman Press, 2002.

Thomas P. Fortune. “The Vermont Brigade at Fredericksburg, December 1862,” in Fredericksburg History and Biography, Vol. 13 (2014).

Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White. Chancellorsville’s Forgotten Front: The Battles of Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, May 3, 1863. Savas Beatie, 2013.

Jeffrey D. Marshall, ed. A War of the People: Vermont Civil War Letters. University Press of New England, 1999.

George W. Parsons. Put the Vermonters Ahead: The First Vermont Brigade in the Civil War. White Mane Publishing, 1996.

Carleton Young. Voices from the Attic: The Williamstown Boys in the Civil War. William James Morris Publishing, 2015.

From a drawing by A. A. Carter, Co. F, 4th Vermont Volunteers

This image shows Sixth Corps troops, including regiments of the Vermont Brigade, attacking Telegraph (Lee’s) Hill on May 3, 1863. Note Braehead on the left, which was once owned by CVBT. An easement was placed on 18 acres around Braehead to prevent future development.

(Jean Findlay)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.