Currier and Ives

(Public Domain)

Introduction

While there were other famous Confederate brigades that fought on the battlefields of central Virginia, few, if any, can claim the amount of overall combat that the five North Carolina regiments commanded by Brig. Gen. James H. Lane experienced at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House. The fate of war seemed to place them in some of the hottest actions on the region’s most contested fields and forests..

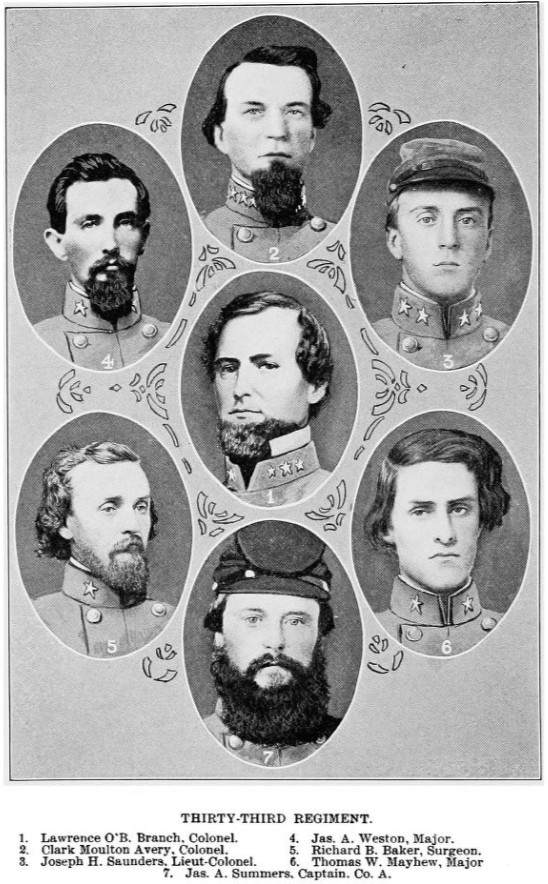

The brigade’s regiments—7th, 18th, 28th, 33rd, and 37th—all organized in 1861. The men who made up these units came from various regions of the Tar Heel State. Some hailed from coastal and tidewater areas like New Hanover and Gates Counties. Many others sprang from the piedmont counties in central North Carolina like Orange and Wake. Still others answered the call for volunteers from the far northwest Appalachian Mountain counties like Watauga, Ashe, and Wilkes.

(Library of Congress)

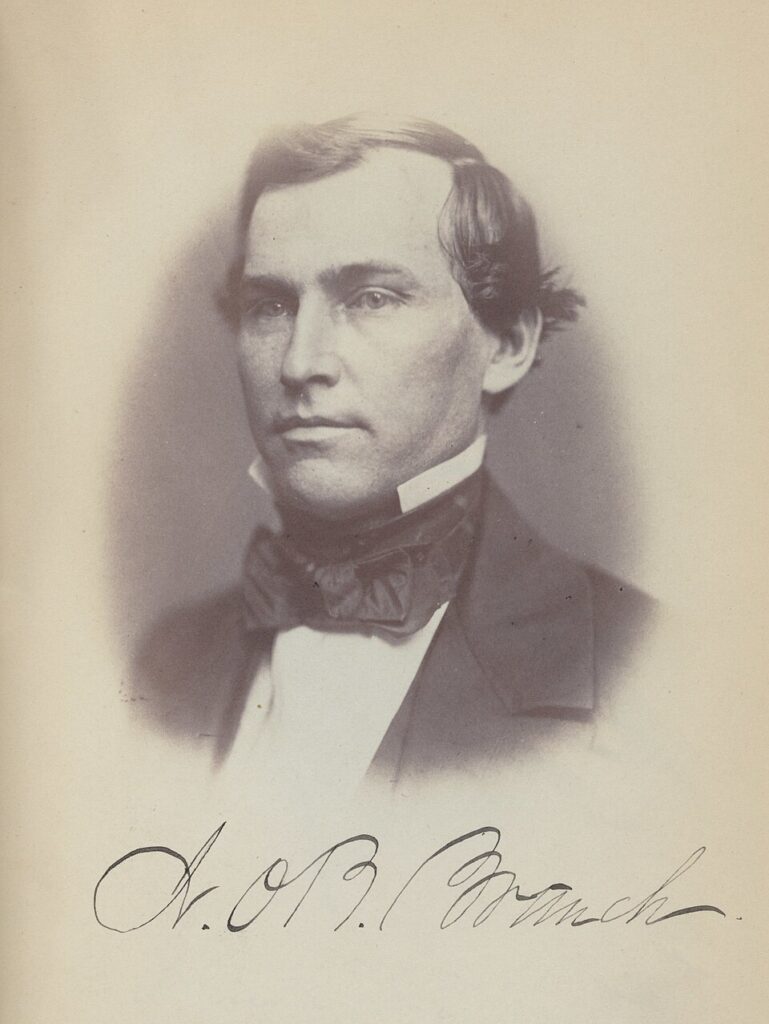

All but two regiments that would eventually compose Lane’s Brigade (18th and the 28th) saw their first true combat at New Bern, North Carolina in March 1862, under Brig. Gen. Lawrence O’Bryan Branch, a former U.S. Congressman and the previous commander of the 33rd. Despite New Bern ending in defeat, soon thereafter the Confederate War Department created a new brigade and assigned it to Branch. After one regiment transferred out and one transferred in, the brigade was mostly set with the five regiments that would serve with it until the end of the war.

More combat came when the brigade received orders to transfer to Virginia and became part of Gen. Joseph Johnston’s command. They joined tens of thousands of others in the Richmond area for what would become an effort to contest Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s slow push toward the Confederate capital with his Army of the Potomac.

Assigned to Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell’s division, Branch’s brigade eventually received orders to go to Hanover County and guard the important railroad intersection. On May 27, 1862, Branch’s brigade had a sharp fight with elements of the V Corps just southwest of Hanover Court House and had to withdraw to Ashland.

A month later, on June 27, Branch’s brigade fought at Gaines’ Mill, where the 7th lost its commander, Col. Reuben Campbell, while he was carrying the colors. At Glendale (Frayser’s Farm) on June 30, Col. Charles C. Lee of the 37th fell killed by an artillery round while in the thick of the fight.

The remainder of the summer of 1862 held plenty of additional fighting opportunities for Branch’s brigade at Cedar Mountain on August 9, Second Manassas on August 29-30, and Chantilly (Ox Hill) on September 1. These three battles produced 306 casualties for the brigade.

As the Army of Northern Virigina moved into Maryland, Branch’s brigade, along with the rest of Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill’s Light Division, participated in the capture of Harpers Ferry on September 15. Called to Sharpsburg to support the rest of Lee’s forces, the Light Division arrived just in time to stem an assault by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps on the south end of the Antietam battlefield. Following the heaviest of the fighting, and as the detached 28th made its way back to the rest of the brigade, Gen. Branch was killed after receiving a wound to the face. Col. James H. Lane of the 28th assumed field command of the brigade.

The brigade’s Maryland Campaign fighting wrapped up with a defensive action at Shepherdstown as the Army of Northern Virginia withdrew back into Virginia. The Harpers Ferry, Antietam, and Shepherdstown fights added another 181 casualties to the brigade’s rolls.

The Battle of Fredericksburg

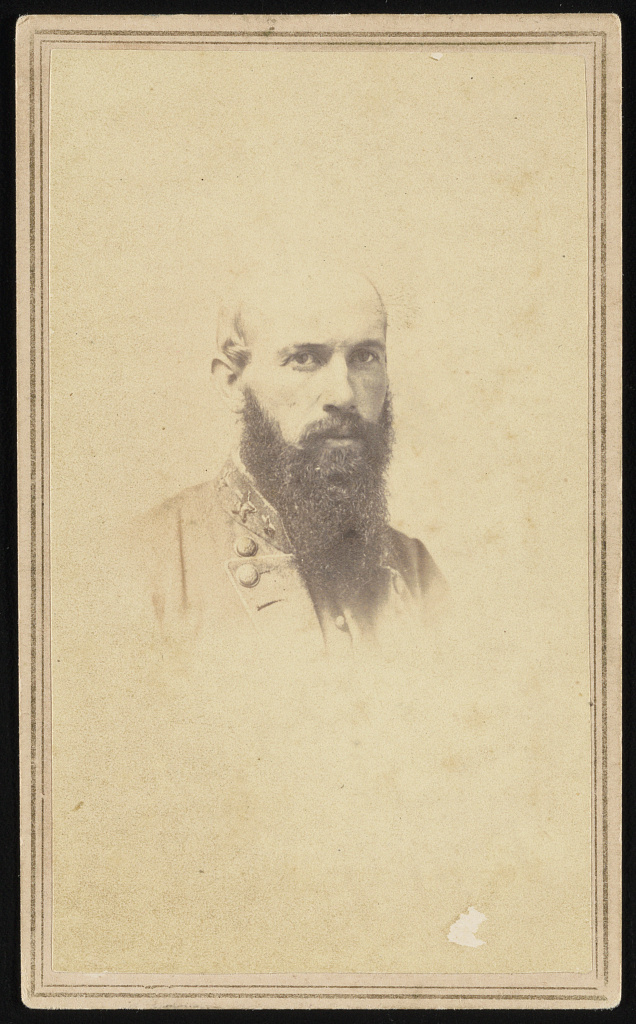

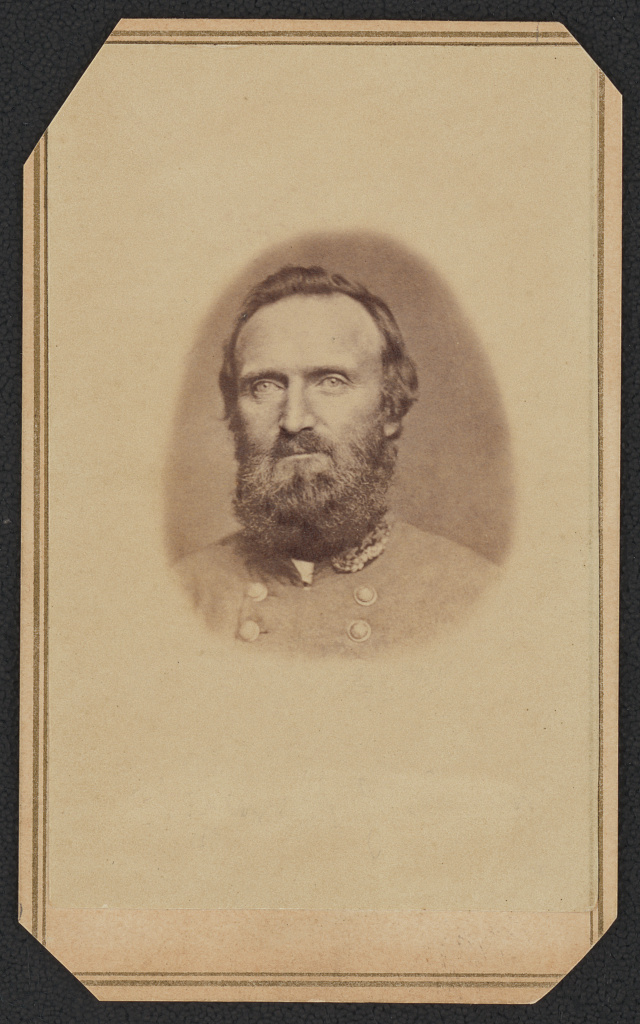

Lane, a Virginia native and VMI graduate, commanded the 28th North Carolina before being officially promoted as Branch’s replacement in November 1862.

(Library of Congress)

Upon their return to Virginia, what before was Branch’s brigade, eventually became Lane’s when he received official promotion to brigadier general on November 1, 1862. It was a position he would hold through the remainder of the war.

Through the next two and a half months an influx of conscripts and exchanged prisoners, as well as returning wounded from the recent campaigns, bolstered the numbers in Lane’s brigade. The new men would soon be needed, as President Lincoln’s dismissal of Gen. McClellan in early November set in motion a series of events that drew the contending armies to Fredericksburg.

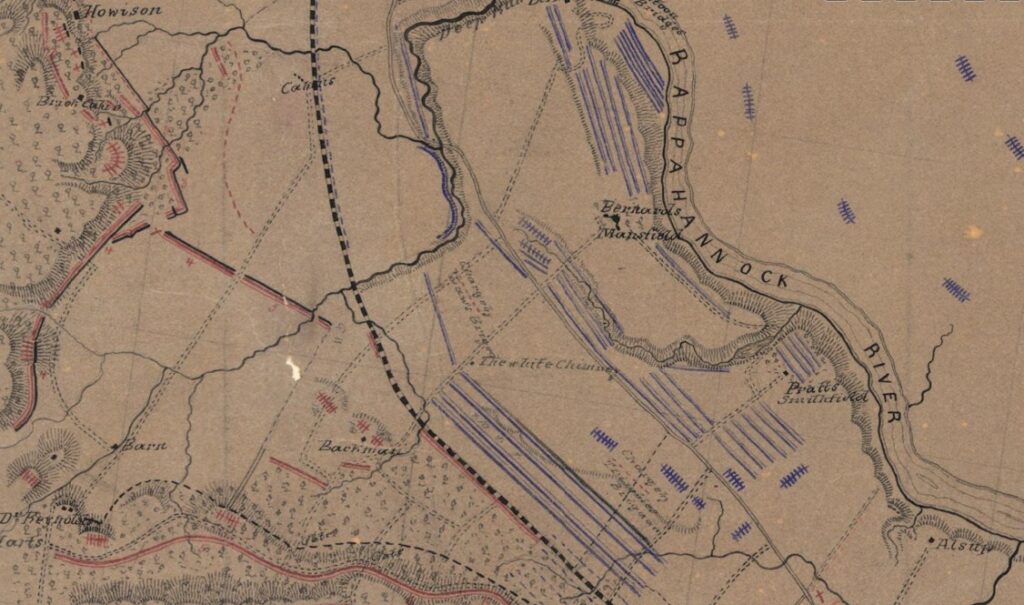

Camped south of Fredericksburg, Lane’s brigade was well positioned to join Gen. Jackson’s defense against the Federal threats at that end of the battlefield. On the morning of December 12, Lane’s North Carolina regiments filed into an advanced position along the west side of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad and where the tracks made a slight bend. Their order from left to right was the 7th, 18th, 33rd, 28th, and finally the 37th. The right of the 37th was near a low, marshy wooded area that remained undefended.

(Tim Talbott)

The following morning, the 7th, serving as skirmishers in the brigade’s front along with the 18th, supported three artillery batteries placed on the east side of the railroad. Federal skirmishers along with a larger force advanced when the fog began to lift. The Confederate artillery “opened with telling effect and checked their advance,” Lane reported. The 7th moved in front of the artillery, which provided cover for the pieces to withdraw to the west side of the railroad.

A bit later, Col. William Barber of the 37th observed a Federal movement by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s division into the undefended area to his right. Barber, holding his ground, refused his right flank in order to defend the ground along the railroad and “became hotly engaged.” While this action occurred on the brigade’s right flank, Brig. Gen. Nelson Taylor’s Federal brigade from Gibbon’s division appeared across their front but was shielded by a rise of ground from the sight of the left part of the brigade. Thus, for a time, the 28th and 37th were taking fire from the front as well as the right. However, as Lane reported, “when the enemy had gotten within 150 yards of our line [the 28th and 37th] opened a terrific and deadly fire upon them, repulsing their first and second lines and checking the third.”

With the 28th and 37th expending their ammunition, as well as most of that found on their dead and wounded, and the Federals adding the weight of Col. Peter Lyle’s brigade to their assault, the right of Lane’s brigade was forced out their strong position along the railroad. Some hand-to-hand fighting occurred before the whole brigade finally had to fall back and reform.

Lane’s brigade fought along the Richmond, Frederickburg, and Potomac Railroad where it makes the bend as shown on this map.

(Library of Congress)

Pvt. Evan Smith of the 28th wrote to his wife Lucy about a week after the battle to let her know he was alright and mentioned this part of the battle. The semi-literate Smith explained, “I hav bin in a fite at Fredrks Burge in Va an[d] we [were] in a ditch on the Rale Rode an we lay ther an shote at the yankeys till we had shote oute of pouder an lede an then thy yankeys charge[d] on us . . . they wear some 4 or 6 colem deap.”

Lane’s brigade received timely assistance on their right from Brig. Gen. Edward Thomas’s Georgia brigade. Lane reported, Thomas “drove them back, and with the Eighteenth and Seventh Regiments of my brigade on his left, chased them to their original position.” Once Lane moved back up the 28th, 33rd, and 37th regiments, he was able to reestablish his line on the west side of the railroad tracks.

The following day, heavy skirmishing occurred between the lines which cost the brigade some more casualties. On December 15, Lane’s brigade made up part of a secondary line, which they fortified. The next day, they learned the Federals had recrossed the Rappahannock River.

As was the case with many soldiers following a battle, the 28th’s major, William Speer, only told his mother that “The great battle the other day . . . was as horrible as you can imagine.” Maj. Speer also mentioned he was thankful that “I came through safe & I do trust that I will be saved through all.”

In Lane’s December 23 official report about Fredericksburg, he stated his brigade suffered 62 killed, 257 wounded, 188 taken prisoner, and 28 missing, totaling 535 men.

The Battle of Chancellorsville

On the morning of May 3, 1863, part of Lane’s brigade attacked across the ground shown in this photograph taken south of the Orange Turnpike.

(Tim Talbott)

A change in commanders for the Army of the Potomac in late January 1863 portended future operations for the armies that watched each other from opposite banks of the Rappahannock River. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker replaced Gen. Burnside and began active movements on April 27. Eventually detected by Confederate cavalry, the Federal maneuvers were reported to Gen. Lee who made plans to oppose Hooker’s advance. Despite being without two detached divisions from Longstreet’s corps, Lee assumed an aggressive posture.

Departing from its location near Hamilton’s Crossing south of Fredericksburg on May 1, Lane’s brigade marched west toward Chancellorsville on the Orange Turnpike. Although not directly involved in the fighting on May 1, Lane’s men suffered some casualties from Federal artillery.

On May 2, Lane’s brigade, along with the other brigades in A. P. Hill’s division, participated in Gen. Jackson’s famous march to position itself on the unprotected right flank of the XI Corps. Lane’s men, apparently at the rear of the Hill’s column, found themselves at the back of the attack column, behind Gen. Robert Rodes’s and Gen. Raleigh Colston’s divisions. Due to their position, they were unable to do much actual fighting while the Federals sparred occasionally with Rodes’s and Colston’s men. Combined with the closing darkness, the difficult landscape and thick woods tended to jumble the attacking commands together.

In the darkness following the well executed May 2, 1863 flank attack at Chancellorsville, the 18th North Carolina of Lane’s brigade accidently wounded Jackson.

(Library of Congress)

During a pause to get the brigades and divisions reorganized, Hill’s division was ordered forward. Lane reported, “Hill ordered me (at dark) to deploy one regiment as skirmishers across the road, to form line of battle in rear with the rest of the brigade, and to push vigorously forward.” The goal was to try to capture Federal batteries in a night attack. About that time, the Federal artillery opened, which brought a response from the Confederate guns. Once they quieted, Lane pushed forward the 33rd as skirmishers and formed his battle line with the other four regiments. Lane placed the 37th south of the road with the 7th on its right. The 18th was on the north side of the road and he positioned the 28th to its left.

It may have been during this movement that the 18th’s Corp. Andrew Profitt described in a letter home soon after the battle. “On Saturday night [May 2] there fell a bomb in my company & exploded in 4 or 5 feet of me & wounded the flag bearer and five or six of my co[mpany] taking off one mans leg & wounded my lieutenant. When the flag of my country fell to the earth I grabbed it with my own hands. My colonel told me to throw down my gear and hold on to my flag which I did,” Proffit wrote.

Unable to find Hill immediately for orders, Lane happened to encounter Jackson who told the brigadier to push forward. Jackson with his staff then rode east on the Orange Turnpike into the darkness.

Federal activity in front of the right flank of the brigade developed a situation where the majority of the 128th Pennsylvania was captured by the 7th. The 7th and the 37th, believing that more of the enemy were in their front, sent a number of volleys into the darkness. Additional commotion at the other end of the line brought fire from the 18th who thought they were being attacked by cavalry. A yell from the front that they were firing into their friends was believed to be a ploy and another volley went forth from the 18th and the 28th. It is a wonder the 33rd’s skirmishers were not decimated, but being spread out in skirmish line formation and in such thick woods likely saved casualties.

However, caught between the 18th in the main line and the 33rd skirmishers were Jackson and Hill and several of their respective staff members, who were in advance of Lane’s brigade gathering information. Jackson suffered wounds from the firing in the right hand, left wrist, and left arm.

The fighting for Lane’s brigade on that long May 2 day was not finished. A heavy advance by elements of the III Corps ran into Lane’s reshuffled line south of the Orange Turnpike. The 28th, 18th, and part of the 33rd took the brunt of the attack, but the darkness and dense woods limited the potential damage. Lane’s men captured some enemy soldiers along with the flag of the 3rd Maine Infantry before things settled down for the night. Any rest that Lane’s brigade got that night was not long.

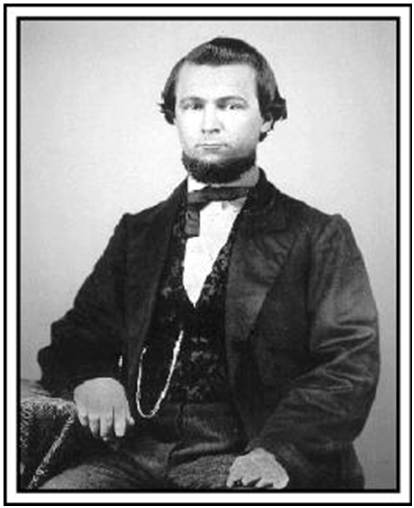

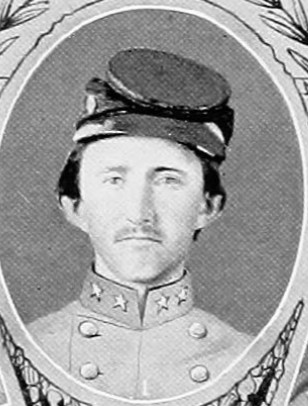

Col. Purdie of the 18th North Carolina was among the four regimental commanders either killed or wounded in Lane’s brigade on May 3, 1863.

(Find A Grave)

At about sunrise on May 3, Lane’s brigade followed the other brigades of Hill’s Light Division in a charge against the Federal line. Starting with the southernmost brigade, James Archer’s, then Samuel McGowan’s on Lane’s right, and finally Lane’s, they all experienced initial success, but the farther they went the tougher it got. During the fighting casualties mounted quickly, particularly among the brigade’s officers. The 18th’s Col. Thomas Purdie was killed, Maj. Thomas Mayhew of the 33rd was mortally wounded, and Lt. Col. Junius Hill of the 7th was killed. Commanders of other regiments in the brigade fell wounded, including, Col. Clark Avery of the 33rd, the 37th’s Col. William Barber, and Col. Edward Haywood of the 7th. Additionally, Gen. Lane’s brother, Pvt. J. Rooker Lane was also killed. Unable to advance further, Lane ordered a withdrawal back to a line of entrenchments.

Unfortunately for some of Lane’s men, Brig. Gen Gershom Mott’s III Corps brigade advanced just as they were withdrawing. Corp. Profitt, who had become the 18th flag bearer the day before got caught between the lines. He wrote his father: “I lay there with two lines of battle cross fireing at me at a short distance & three batteries throwing grape at me not more than 3 or 4 hundred yards distant. The first I knew the yanks were in five steps when two jumped over the breast works & grabbed the flag out of my hand & said to me fall in John ha ha ha. John fell in but did not like to do it,” Profitt explained. The 7th New Jersey received credit for capturing the 18th’s colors.

Being the southernmost regiment in the brigade, the 28th became separated during Gen. Lane’s withdrawal. The space allowed other units to advance and the 28th went forward with them. They took additional casualties while making three charges. The 28th’s Maj. Speer, who was wounded the day before, but was observing on his horse, wrote home after the battle, “Oh Father the scene was awful. I cannot describe it to you as it was and will not try.”

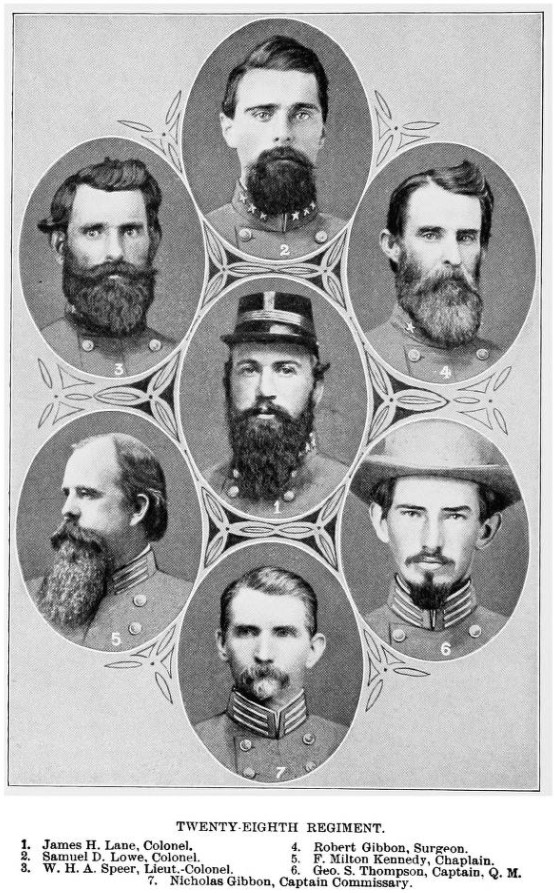

(Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-1865, Vol. II, 1901)

After reforming and resupplying the 7th, 18th, 33rd, and 37th with ammunition, Lane moved those regiments to the north side of the Orange Turnpike in support of Alfred Colquitt’s Georgia brigade. Lane noted in his report: “The woods which we entered were on fire; the heat was excessive; the smoke arising from burning blankets, oil cloths, &c., very offensive. The dead and dying of the enemy could be seen on all sides enveloped in flames, and the ground on which we formed was so hot as at first to be disagreeable to our feet.”

Other than some skirmishing, Lane’s men spent an uncomfortable next few days picketing the retreating Federals near the Rappahannock River before returning to their camps on May 7.

Gen. Lane’s May 11 report of the battle listed 909 casualties in the brigade, however, an accounting by Surgeon Lafayette Guild, the Medical Director of the Confederate Army, listed Lane’s casualties as 739. Regardless of the exact number, the brigade suffered heavily, particularly in experienced commissioned officers, who were obviously difficult to replace.

(Library of Congress)

With such high losses, some Confederates found it challenging to celebrate the victory. Some spent time scavenging the battlefield picking up useful items and food. Others wrote home. The 37th’s Pvt. Thornton Sexton did just that, requesting food: “I Can in form you that I have not had nothing to eat in two days an I am al Moost starved[.] I want you Bring Mee a box of pervines [provisions] if you Can[,] for times is hard hare now,” Sexton wrote. He assured his father of his safety by explaining: “i Com thru the Battle Safe an Was not hirt[.] Maryin [brother Marion] was not hirt [.] it was Bad looken times[.] the trees an bushes was coot all to peses[.] With balls an grap shoot.” Turning to his mother, Sexton wrote her, “I would like be at hom if I cood mitey Well[.] i never node what bad times [were] before in my life[.] all my frends my best respets i gve them[.] I hauve not received no mooney Sence I was at home[.] i need somthing to eat Mity bad if i cood git it.” In closing, Sexton asked for a return letter.

Once back in camp, the 18th’s Pvt. James Huffman wrote to his wife on May 8 letting her know he was not killed. Huffman explained “I am glad to state that I was not slain during the fight but slightly wounded. I had the middle finger of my left hand shot off, two balls passing through my knapsack & haversack, so I was struck 3 times but fortunately but one [finger] took off. I had my finger taken off by the doctor at the upper joint in the hand. I am getting along very well considering and hope I will get to come home soon.”

The Mine Run Campaign

After seeing additional fighting at Gettysburg, including the famous charge on July 3, 1863, Lane’s brigade and the Army of Northern Virigina returned to central Virgina for a late fall campaign.

Fortunately for Lane’s men, they missed the fighting at Rappahannock Station on November 7. However, the following day they participated in a skirmish with Federal cavalry in Culpeper County that resulted in about a dozen casualties for the brigade.

Being in A. P. Hill’s corps, Lane’s North Carolinians also escaped the primary fighting at Mine Run. However, they did get in some skirmishing along with building fortifications. Capt. John D. Fain, who had just transferred to the 33rd from the 12th North Carolina, wrote to his mother on December 6 that “We had fortified ourselves very securely when we were threatened by the enemy and they pushed very closely upon us. It was very exciting—the skirmishers would sometimes be driven in and we would all rush from our fires to the breastworks. The sharpshooters from our brigade killed several [of the enemy].”

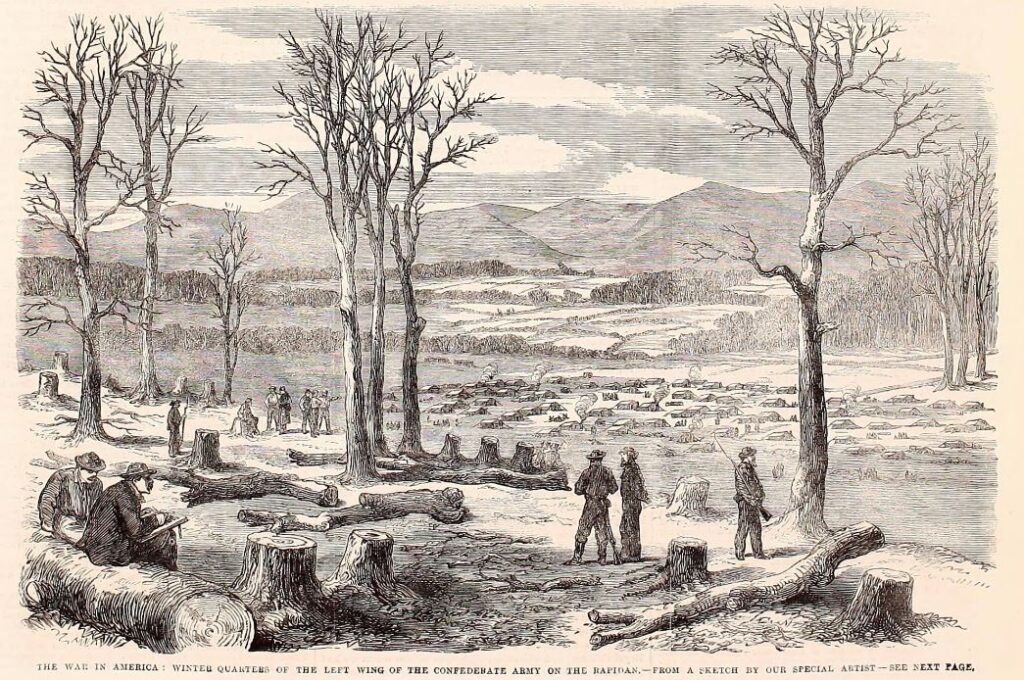

Lane’s men settled back into a winter quarters routine in Orange County after Meade decided to call off the offensive and recross the Rapidan River back into Culpeper County.

(Illustrated London News)

The Battle of the Wilderness

(Tim Talbott)

On May 4, 1864, after about five months of inactivity in winter quarters, Lane’s brigade, along with the rest of Gen. A. P. Hill’s corps, received the call to push east on the Orange Plank Road to meet a Federal thrust.

Lane’s five regiments covered the majority of the required distance before going into camp at Verdiersville. Picking up their march on May 5, they soon heard musket fire and the report of an occasional artillery piece. Deployed to the north side of the Orange Plank Road, along with rest of Gen. Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox’s division, they made their way forward in battle line as best they could through the dense stands of young trees, bushes, and briar vines. Encountering Federal soldiers from Gen. Wadsworth’s division near the Chewning Farm, the North Carolinians were able to capture dozens of the foe before they could get away.

Soon Wilcox’s division received orders to reinforce Gen. Henry Heth’s division that had been battling Hancock’s II Corps divisions along the Orange Plank Road just south of its intersection with the Brock Road. There they found Gen. Alfred Scales’s brigade in their front but being driven back. Ordered to advance through the difficult thickets and swampy ground, Lane’s men forced the Federals to withdraw a distance.

The evening darkness, along with the dense forest, made discerning one’s enemy nearly impossible at just about any distance. Keeping lines in order within regiments, let alone across the brigade, was virtually impossible. Taking prisoners on both sides was common during the evening and night hours, as soldiers were unable to tell friend from foe until it was too late to get away.

After a tough afternoon and evening of fighting, during the night hours, Gen. Hill, apparently unwilling to allow his frontline troops to be disturbed, and believing that Gen. James Longstreet’s troops would relieve his part of the line early the next morning, did not have his men dig in or improve what works they already had.

When Hancock moved his II Corps forward like an avalanche on the morning of May 6, Wilcox’s and Heth’s divisions stood little chance in holding them back without significant fortifications. Confederate brigades rolled back on each other like tumbling dominoes.

During the retreat by the 18th, Alfred Proffit was wounded. He wrote to his sister later in the day from Orange Court House. “The[y] fired a signal gun and they then charged and the first fire the infernal rascals fired the[y] put it to me[.] I was struck just a bove the right Eye[.] It split me to the Skull a bout three inches, and you can guess if I dident git away from thare[.] I left A.j. [his brother] thare I have not heard from him cince I am now at the hospittal at orange.”

(Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-1865, Vol. II, 1901.)

Partly inspired by the bravery of its colonel, Clark Moulton Avery, the 33rd maintained its place in line for a time. Standing behind some improvised works, Col. Avery was heard to say, “we will give them one volley before we go,” when he received a wound to left arm. Attempting to further inspire his men, Avery remained on the field, albeit on a stretcher, before finally retreating. He was hit four more times during the withdrawal. He died a month and a half later from his wounds.

The arrival of Longstreet’s corps proved fortunate for Hill’s corps. With the weight of Longstreet’s divisions stalling out Hancock’s assault, Hill’s men were able to gain enough space and time to get reorganized. Occupying the terrain between Ewell’s corps on the left and Longstreet’s on the right, Lane’s brigade fortified their position during the evening and night of May 6.

Lane reported that he lost 415 men killed, wounded, and missing during the Wilderness fight. The 33rd lost the most with 111, while the 7th suffered just five less than the 33rd.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

(Public domain)

On May 8, Lane’s brigade marched from the Wilderness battlefield to Spotsylvania where they arrived around midday on May 9. The brigade “at once entrenched on the left of the road leading to Fredericksburg—our right resting on the road,” Lane reported. Additional movements occurred on May 10. In a likely reference to Col. Emory Upton’s Federal assault on the opposite side of the Mule Shoe salient, Lane explained, “That night we moved very rapidly to the support of a part of Ewell’s command, but not being needed, we were ordered back . . . .” Lane’s five regiments worked on strengthening their lines on May 11, spending a good deal of the day working in the rain in a position he deemed more appropriate, just outside the main salient line.

Positioned as they were on the east side of the salient, Lane’s brigade was sure to see some heavy fighting on May 12 when a massive Federal attack hit the salient in multiple places. With Lane’s leftmost regiment to the right of Gen. George H. Steuart’s overrun brigade, the left and rear of the 28th and 18th became vulnerable from the II Corps breakthrough and thus lost a number of men as prisoners. Also attacking, but against Lane’s front, was Col. Simon Griffin’s IX Corps brigade. Col. William Speer of the 28th wrote in his diary that day, “I found the troops on my left flying in utter confusion in every direction. [I] found the enemy coming down the works on both sides.” Falling back to “an arm of the old works,” Lane was able to get his other three regiments set and the other two rallied to them.

(Tim Talbott)

Here, Lane reported, “the brigade welcomed the furious assault . . . with prolonged cheers and death dealing volleys . . . thinning the ranks of the enemy in front, while the rest did good execution in the rear.” Col. Speer noted in his diary, “Here took place one of the most desperate fights of the war.” Lane seemed to concur, “men could not fight better, nor officers behave more gallantly. . . .”

Lane soon called for reinforcements. Division commander Maj. Gen. Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox sent Lane Brig. Gen. Alfred Scales’s North Carolinians and Brig. Gen. Edward Thomas’s Georgians. Arriving, too, was Brig. Gen. George Doles’s Georgians from Ewell’s corps. Doles suggested Lane counterattack. Lane launched forward and dove into the IX Corps units that had attacked him in front earlier, pushing the Federals back about 300 yards. Wilcox then ordered Lane to return to the main works. Finding the line crammed with soldiers, Lane repositioned further to the right just south of a location known as Heth’s salient. At about this time, Gen. Lane’s staff officer brother, Lt. Oscar Lane, was mortally wounded by an artillery shell.

Lane’s brigade served in Wilcox’s division from August 1863 through the end of the war.

(Library of Congress)

There was yet more offensive action in store for Lane’s brigade on that long, fateful May day. Soon after coming into their new position in line, and after reconnoitering the left flank of the IX Corps units and finding it unprotected, Lane received orders from Gen. Jubal Early, who was commanding the Third Corps in A. P. Hill’s absence, to attack immediately along with support from Col. David Weisiger’s brigade of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s division. The assault’s goal was to silence the Federal artillery enfilading part of Heth’s salient, slam into the left flank and rear of the IX Corps, and thus create enough of a disturbance that it would relieve the tremendous stress on the Confederate line at the “Bloody Angle.”

About this action, Lane reported, “My men . . . moved forward very handsomely . . . drove the enemy’s sharpshooters out of the oak woods, rushed upon their battery of six guns . . . and struck Burnside’s assaulting column in flank and rear.” The 28th’s Col. Speer noted in his diary “Some of the guns would not fire having been rained upon during the morning, but the men charged ahead with the bayonet. . . . My Regiment took more prisoners than I had men engaged. . . . Some of my men fought with anything they could get hold of.” Lane particularly praised the 37th. According to Lane, the 37th “had the best opportunity of displaying its bravery, as it was immediately in front of the four pieces that were turned upon us, and suffered heavily from canister. I have never seen a regiment advance more beautifully than it did in the face of such a murderous fire.”

Although Lane’s men were unable to bring the captured artillery off the field “for want of horses, and because there was no road by which we could bring it off by hand,” the attack achieved its primary objective, and Lane ordered the brigade to fall back to the earthworks.

Gen. Lane tabulated that his brigade lost 470 officers and men killed, wounded, and missing on May 12.

Fortunately for the brigade, the majority of their fighting at Spotsylvania was over. According to Lane, they spent most of the remaining week manning portions of the earthworks, “strengthened old works, built new ones, and sometimes marched in support of other commands, but were not actively engaged.”

However, a final skirmish on May 21 occurred southeast of Spotsylvania Court House that involved the brigade. Of the fight Lane noted, “we then advanced through an almost impenetrable abattis, dislodged and drove back a strong line of the enemy’s skirmishers, and held their main line of breastworks until after dark, when we were ordered back. . . .” Col. Speer wrote in his diary that day that his regiment “was exposed to a most terrific shelling and did heavy skirmishing all day.” He lost five men, including Lt. E. S. Edwards who was killed. The brigade lost 18 men in this final action at Spotsylvania.

Conclusion

Lane’s brigade would witness more significant fighting before the end of the war. They participated at North Anna and Cold Harbor (where Lane was wounded) to finish out the brutal Overland Campaign, and fought in various actions around Petersburg, like First and Second Deep Bottom, Ream’s Station, and Peebles Farm.

In February 1865, the 7th was detached to North Carolina to round up deserters. Their absence left the already thin brigade even more shorthanded when they received the concerted assault by the Army of the Potomac’s VI Corps on April 2, 1865, just southwest of Petersburg. With their earthwork lines broken, and many men captured, the remnant of Lane’s brigade evacuated Petersburg and joined the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia in its retreat west before surrendering at Appomattox.

Sources and Suggested Additional Reading

Walter Clark. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-1865, Vol. I and Vol. II. Nash and Brothers, 1901.

Michael C. Hardy. General Lee’s Immortals: The Battles and Campaigns of the Branch-Lane Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865. Savas Beatie, 2018.

Michael C. Hardy. The Thirty-seventh North Carolina Troops: Tar Heels in the Army of Northern Virginia. McFarland, 2003.

James Lane. “History of Lane’s North Carolina Brigade,” in the Southern Historical Society Papers, Vols. 7-10, 1879-1882.

Allen Paul Speer. The Civil War Diary, Reports, and Letters of Colonel William Henry Asbury Speer (1861-1864). The Overmountain Press, 1997.

Parting Shot

“Lt. Col. Hill, had at Chancellorsville, on the 3d of May, about 8 o’clock in the morning, while in command of his regiment, routed the enemy from their works, and was encouraging his men to hold the place until reinforcements might arrive, when he fell pierced through the neck by a minnie ball, and died without struggle.” North Carolina Standard, May 19, 1863

(Image: Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-1865, Vol. I, 1901.)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.