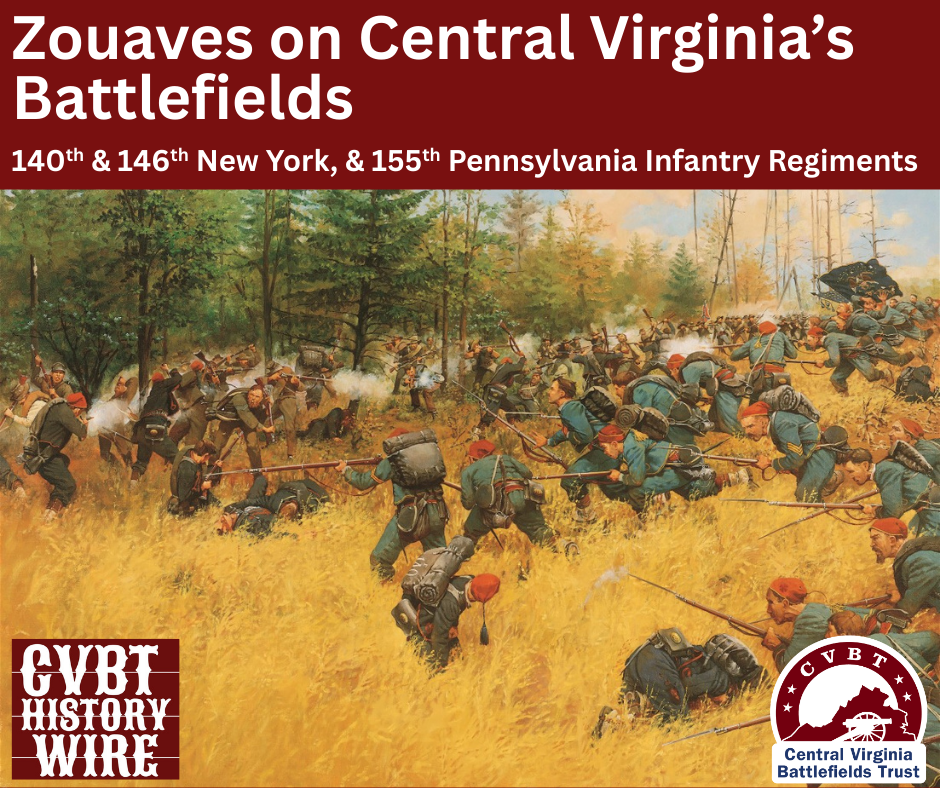

(Keith Rocco)

Introduction

In last month’s CVBT History Wire, we shared the story of the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry (Collis’ Zouaves), focusing particularly on the parts they played in the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, as well as some background information on Zouaves in general. If you would like to read that post, you may do so here.

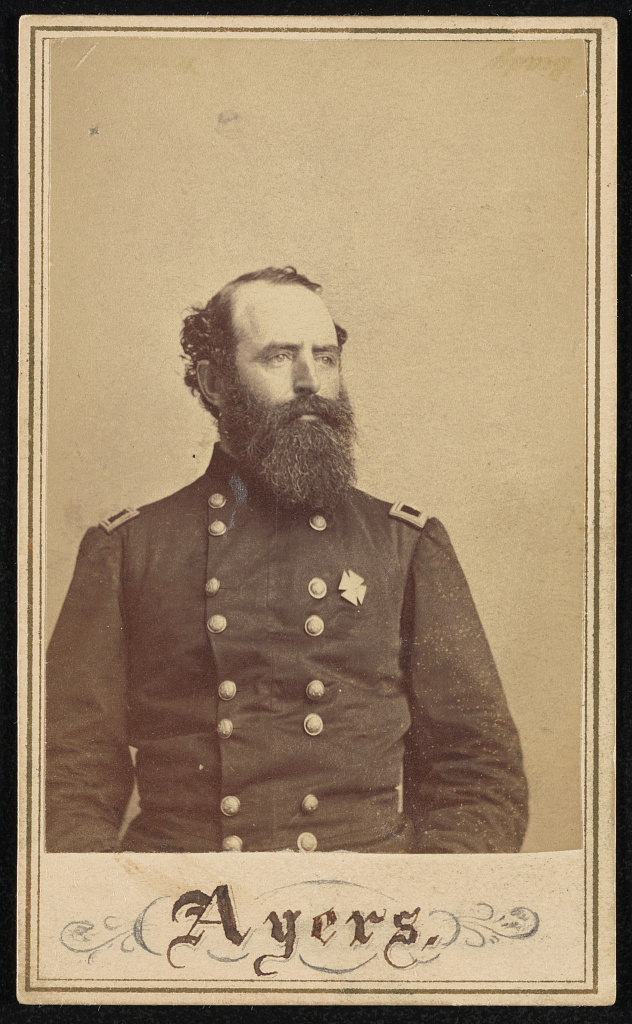

For this month’s CVBT History Wire, we will examine three Zouave regiments and their experiences fighting in Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s Fifth Corps at the Battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. These three regiments, the 140th and 146th New York, and the 155th Pennsylvania, all served in Brig. Gen. Romeyn Ayers’ First Brigade of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s First Division. They would be among the initial Union troops to open fire in what would become the grueling Overland Campaign.

Although sometimes called the “Zouave Brigade,” Ayers’ brigade only contained these three Zouave units. The non-Zouave regiments included the 91st Pennsylvania, and the 2nd, 11th, 12th, 14th, and 17th U.S. Infantry (Regulars).

In addition to Ayers’ First Brigade, Griffin’s division also included Col. Jacob Sweitzer’s Second Brigade and Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Bartlett’s Third Brigade

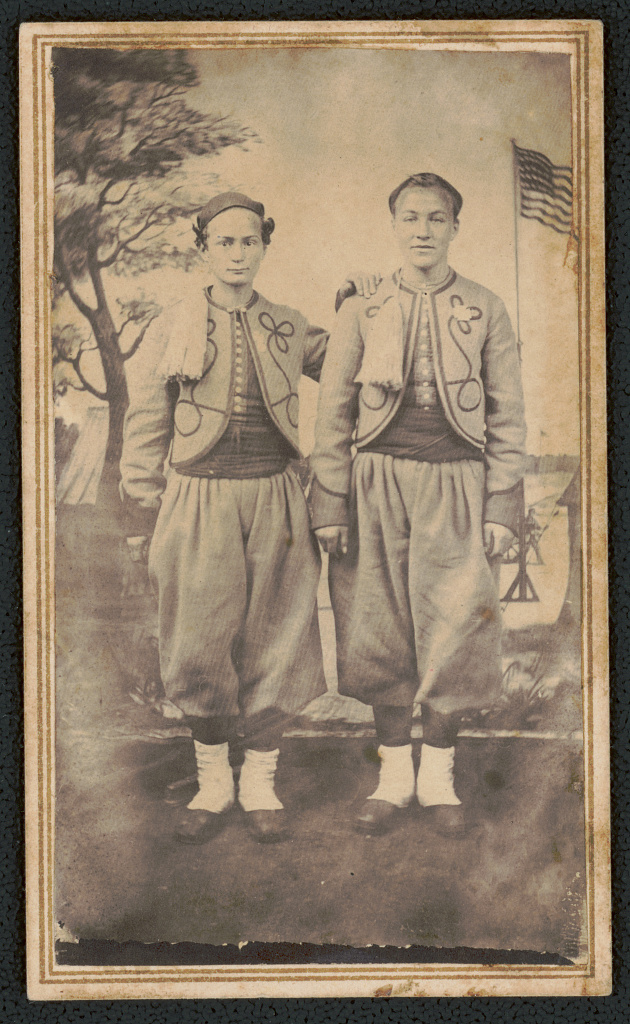

(Library of Congress)

Backgrounds of the 140th and 146th New York, and 155th Pennsylvania

Infantry Regiments

140th New York Infantry

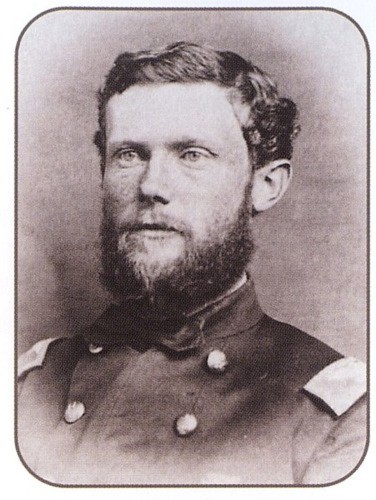

Organized in September of 1862, following President Abraham Lincoln’s summer call for more volunteers, and composed of men primarily from the Monroe County, New York, area, the 140th New York was originally led by Col. Patrick H. O’Rorke, a West Point graduate in the class of 1861.

Initially assigned to the Twelfth Corps, the “Rochester Racehorses,” as they were sometimes called, received a transfer to the Fifth Corps in November 1862, in time to participate in the Battle of Fredericksburg. Largely held out of action, they suffered few casualties. Other than some action on the first day, the 140th missed most of the Battle of Chancellorsville, too. At Gettysburg, however, they held an important position at a key moment on Little Round Top. There, Col. O’Rorke was killed, shot through the neck. The regiment suffered significant casualties defending their position.

Col. George Ryan, an 1857 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, assumed command of the regiment in July 1863, leading it during the fall and winter campaigns in northern and central Virginia. It was under Ryan’s guidance, and in recognition of the regiment’s exemplary drill and discipline, that they received authorization for Zouave uniforms in early 1864, just in time for some of their greatest trials.

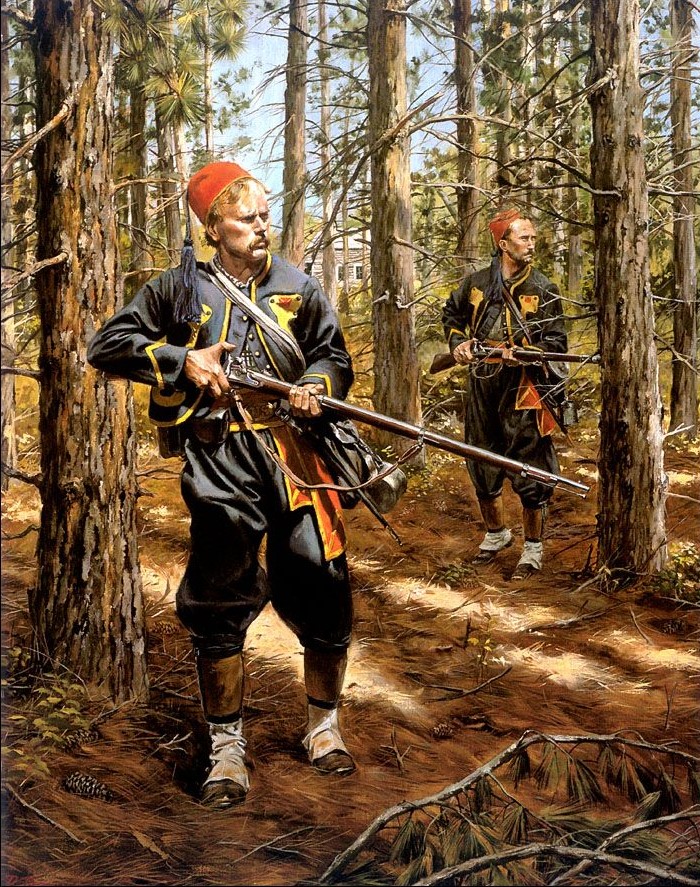

Consisting of dark blue baggy trousers, short dark blue jackets with red embroidered highlights, white shoe gaiters and accompanying brown leather jambiers, and topped with red fezzes with tassels, the Zouave uniforms of the 140th New York presented a striking image.

The regiment’s Porter Farley remembered that “When I rejoined [the regiment after a leave], on [January] 16, [1864] I found a very great, though not unexpected, change. The regiment had received and put on the blue zouave uniform, which it ever afterward wore.” After describing their new outfits, Farley recalled, “With some modifications I regard it as the best uniform for an active campaign. The baggy trowsers certainly possess great advantage over any other kind. They wear much longer and are far more comfortable, both to march and sleep in. Their pockets are almost equivalent to a second haversack.”

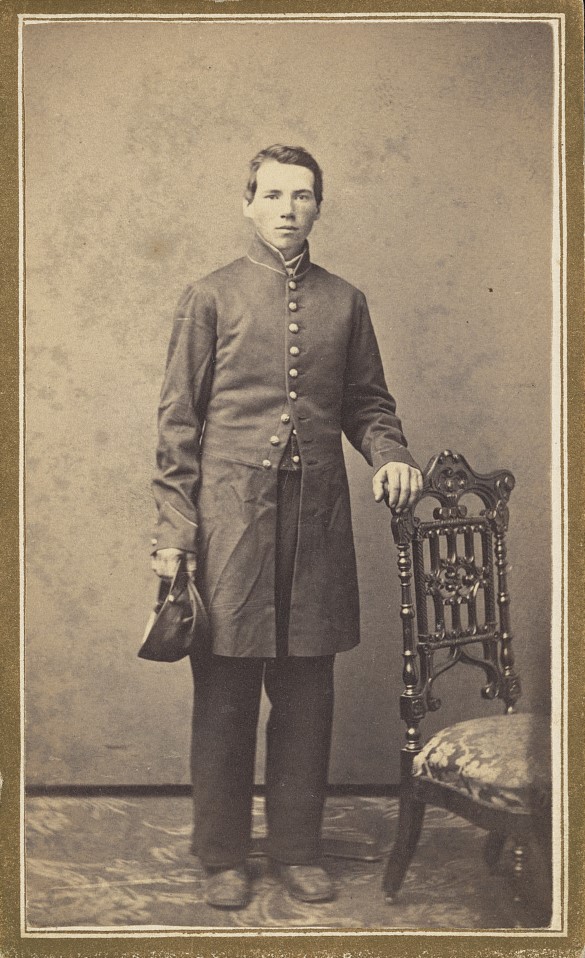

(Library of Congress)

146th New York Infantry

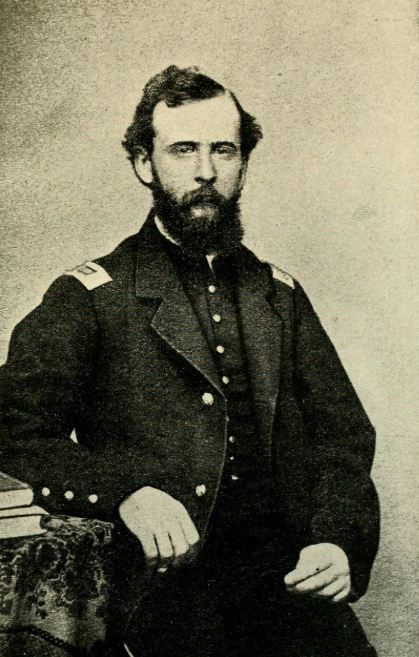

Composed mainly of men from Oneida County, New York, the 146th New York was first commanded by Col. Kenner Garrard. The 146th, also known as “Garrard’s Tigers,” like the 140th New York, was a fall 1862 regiment. The two regiments actually shared a long history together as they served in the same brigade beginning in November 1862.

As was the case with the 140th, the 146th sustained minimal casualties at Fredericksburg and was only involved in the May 1, 1863, fighting at Chancellorsville.

About a month after Chancellorsville, over 200 men who had previously served in the 5th New York Infantry (Duryee’s Zouaves) and who had signed three-year enlistments transferred to the 146th, when the majority of the 5th New York’s two-year men mustered out.

On June 3, 1863, possibly as a way of recognizing the proud service of the 5th New York Zouaves, the 146th adopted a Zouave uniform style. While it was of typical Zouave cut and fashion, it departed slightly from traditional Zouave colors. Instead of dark blue or red baggy trousers, the 146th chose light blue pants, their short jackets being of the same color. Instead of red trim highlights on their jackets, the 146th chose yellow. A red fez with yellow tassel served as their head gear, which could be combined with a white turban on dress occasions. The regiment’s chronicler noted, “The first dress parade succeeding the receipt of our new uniforms was a most brilliant affair. We had no end of fun in dressing ourselves preparatory to it, for there were many things about our new costumes which some of us did not understand.”

Serving with the 140th New York on Gettysburg’s Little Round Top, but arriving as the Confederate assaults began to slack, the 146th endured fewer casualties than their comrades in the 140th. Col. Garrard received promotion to command the brigade after Brig. Gen. Stephen Weed was killed in the July 2 fighting. With Garrard’s advancement, Lt. Col. David Jenkins became commander of the regiment.

After campaigning into the fall and winter of 1863, the 146th eventually settled down into winter quarters at Warrenton Junction. The soldiers spent their time building shelters, hoping for care boxes from home, and drilling. Pvt. Charles Brandegee, writing to his brother in February 1864, stated, “Things jog in their usual course here, yesterday our Brig[ade] was reviewed by Gen’l Ayers Staff and wife. As our Brig is composed of 3 Zouave Regiments it presented quite an appearance. ‘A terror to all rebels.’”

(Don Troiani)

155th Pennsylvania Infantry

(Don Troiani)

Raised from men in Pittsburgh and western Pennsylvania, and formed in September 1862 under the command of Col. Edward Allen, the 155th Pennsylvania was fortunate to just miss out on the Battle of Antietam. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, the 155th served in Col. Peter H. Allabach’s brigade, which was part of the division commanded by Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys, and saw significant combat while attacking Marye’s Heights. Sgt. George P. McClelland wrote his sister about his experience at Fredericksburg: “Our 1st Lieutenant was wounded on one side of me and several of the [wounded] boys on the other were crying for their comrades to take them off the field. It was a wonder I escaped. I stood on my feet and took as deliberate aim as I could. They shot a piece of my gun away. . . .”

Still in Allabach’s brigade during the Chancellorsville Campaign, the 155th spent time guarding fords, digging field entrenchments, supporting artillery near the Chancellor house, and serving as rearguard troops. These duties limited their direct exposure and thus their casualties.

Soon after Chancellorsville, the 155th transferred to Brig. Gen. Stephen Weed’s brigade (Brig. Gen. George Sykes’ division), which included the 140th and 146th New York, and the 91st Pennsylvania. During the Battle of Gettysburg, they fought with their brigade-mates on Little Round Top on July 2, 1863. Still fighting with smoothbore muskets at that point, the 155th inflicted significant casualties upon the assaulting Confederates without sustaining many themselves.

Led during the Battle of Gettysburg by Lt. Col. John H. Cain, due to Col. Allen’s ongoing sickness, Cain became the regiment’s commander when Allen resigned due to disability following Gettysburg. Leadership change came to the brigade as well when Weed was killed in the Little Round Top fighting and its command went to the former colonel of the 146th New York, Kenner Garrard, who led the three Zouave regiments until February when command went to Col. George Ryan, the former (and future) commander of the 140th New York.

According to the 155th’s Lt. J. A. H. Foster, their camp was buzzing in January 1864 about new uniforms: “There is nothing of any importance going on about camp with the exceptions of the boys talking about the new uniform they are appealing to get. It is a ‘Zouave Uniform’ dark blue pants and round about [jacket]. The pants are wide and to be worn with leggings. The cap is a red Fez . . . with blue tassel. The sash is red with blue trimming, (that is the edges is bound with red.) It will look very well I think. Some of the men are anxious to get them while others are much opposed to them. For my part I don’t care whether they get them or not. It is very little difference to me [just] so my clothes are comfortable.” The uniforms of the 155th Pennsylvania were similar to the 140th New York’s expect the 155th jackets had yellow trim instead of red trim.

In the March 1864 army reorganization, the 155th Pennsylvania and the two New York Zouave regiments, along with the 91st Pennsylvania, were transferred to Romeyn Ayers’ brigade, joining force with Ayers’ regulars.

The Battle of the Wilderness

running east and west.

(Tim Talbott)

By the spring of 1864, the three Zouave regiments of Ayres’ brigade were all well drilled and had gained valuable experience in combat situations, and were seasoned to camp life. However, they would soon face their greatest combat trials.

On May 1, 1864, Ayers’ brigade broke their winter camps near Rappahannock Station, crossed the river, and moved the short distance to Brandy Station, where they stayed until May 3, when they pushed south at about 11:00 pm. Early the next morning, with Sheridan’s cavalry leading the way, they crossed the Rapidan River at Germanna Ford at about 6:00 am and encamped along the north side of the Orange Turnpike, not too far from the Lacy House, Ellwood, which was across the road.

With Gen. Griffin receiving orders on May 5 from Gen. Warren to move west along the Orange Turnpike, Ayers’ brigade led the march at about noon.

The 140th New York, their left flank resting on the north side of the road, advanced along with the five units of Ayers’ U.S. Regulars to their right. Forming the second line was the 146th New York, which was directly behind the 140th. To the right of the 146th was the 91st Pennsylvania, and then the 155th Pennsylvania. Expecting to fight immediately, the regiments dropped their knapsacks and placed guards over them. Skirmish fire began up the road, and Confederate artillery threw some iron eastward at the gathering Federals.

Pushing ahead through the tangled Wilderness toward their skirmishers proved challenging for Ayers’ men. Soon, however, the 140th emerged into a cleared area known as Saunders Field. In front of them, roughly halfway across the field, a small dip in the terrain created a shallow ravine that ran roughly perpendicular to the road, then the ground rose toward the west end of the field. Standing on the rise were Confederates in Brig. Gen. George Steuart’s mixed brigade of North Carolina and Virginia regiments from Maj. Gen Edward Johnson’s division, Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Corps.

Amazingly, he survived unscathed.

(Don Troiani)

Steuart’s men let loose a long-range volley as the 140th showed itself entering Saunders Field. In addition to several men being hit, Col. Ryan’s horse took a bullet that made the animal unmanageable, so Ryan dismounted. The colonel ordered the men to lie down and fix their bayonets. Quickly, Ryan ordered the men to stand and charge. Lt. Porter Farley recalled, “Colonel Ryan was with us, he and I running so near together that we exchanged words as we went across the field. Veering toward the road, the 140th ended up straddling the thoroughfare by the time they reached their foe in the wood line at the west end of Saunders Field.

Taking casualties while crossing the field, Ryan continued to lead the men, waving his hat, as he had left his sword with his wounded horse. “He was full of energy, and though we were in a forest he showed himself at every point of our thin line during those few desperate minutes,” Lt. Fraley remembered of Ryan.

Outpacing their U.S. Regular comrades on their right, who had to stumble through the tangled woods rather than across an open field, the 140th, now back in the woods themselves after pushing their enemies, quickly became vulnerable on their right flank. Hit hard by the Confederates from that end, “The regiment melted away like snow. Men disappeared as if the earth had swallowed them,” noted Farley. He added, “Every officer about me was shot down.” Confusion reigned amidst the smoke, flying projectiles, noise, and thick woods. With so few officers still standing, the enlisted men looked for leadership that was now terribly missing.

(Tim Talbott)

(Tim Talbott)

In an attempt to assist the 140th, a section of Battery D, 1st New York Light Artillery under the command of Lt. W. H. Shelton rolled west on the turnpike into position, and although its men and horses took numerous hits, it unlimbered and threw canister toward the Confederate line. Unfortunately for the 140th, the artillerymen caused injury to friends and foes alike.

Within a few minutes, the second line, consisting of the 146th New York and the 155th Pennsylvania, along with the 91st Pennsylvania sandwiched between the two Zouave units, came up in an attempt to support the right of the 140th New York. With fixed bayonets, they rushed forward. About the time that the 146th New York crossed the shallow ravine, they were hit with a couple of volleys from the Confederates. “Many threw their arms wildly in the air as they fell backward, the death-rattle in their throats. Others, wounded more or less severely, reeled in their tracks and collapsed upon the field or staggered to the rear in search of aid,” noted their regimental history. One of the wounded was the 146th’s color-bearer, George F. Williams, hit by three bullets. Another member of the color guard grabbed the flag, who soon fell killed. Corp. Conrad Neuschler, the only remaining uninjured man of the color guard, took up the flag and was heading for the rear when he stumbled and fell and was then wounded. Sgt. J. Albert Jennison, seeing Neuschler fall, grabbed the flag and, “dodging the bullets they fired at him by bounding from side to side like a rabbit,” Jennison kept the flag safe, making it safely to the rear.

(Find A Grave)

Led by Col. David Jenkins, the 146th New York plunged forward, moving across Saunders Field, taking casualties at the shallow ravine and then moving into the Wilderness at the double quick on the west end of Saunders Field. Some amount of hand-to-hand fighting occurred among the defenders and the surviving attackers. Like the 140th New York before them, the 146th had outpaced its right flank units. The Confederate brigades of James Walker (Virginians) and Leroy Stafford (Louisianians), “signaled their approach by one of their demoniac battle-yells and at the same time poured a volley” into the right flank of the regiment. According to the regimental historian, “The result was a complete rout, and escape to the rear became the only alternative to being killed or captured.”

If the force of Confederate fire from the attack on their right was not enough, Ayres’ brigade also endured Gen. John M. Jones’ Virginia brigade on their left flank. The game was up. “We were in a bag, and the string was tied,” noted Capt. W. H. S. Sweet of the 146th. Lt. Farley of the 140th remembered: “We were nearly cut off, but taking our only chance for escape started back across the open field.” Fleeing with Sgt. John McDermont by his side, Farley claimed, “it seemed as if bullets flew about faster than ever, and I was never more surprised in my life than when we reached unhurt the shelter of the wood on the [east] side [of Saunders Field].

Being on the end of the line receiving the primary flanking maneuver by the Confederates, which was in the thick woods, the 155th Pennsylvania had little opportunity for a stand-up fight. The regimental history of the 155th paints a picture with words: “As if to hide from view the victims of man’s wrath, everywhere a gentle steady rain of twigs and leaves was falling to the earth, pruned by the same hail that penetrated the flesh and splintered the bones of the devoted men of the few regiments that vainly fought to destroy or at least check this terrific onslaught.” The dense woods also kept the standard of the 155th “tightly furled around the staff,” as there was “No room among the thorns and briars of that enslaving jungle to unfurl the flag.” Despite demands to surrender, Sgt. Thomas C. Lawson beat feet to the rear, running through a thicket of briars, as did Color-Sergeant Thomas Marlen, saving the colors. Some of the Keystone State Zouaves carried wounded comrades back to their original lines. Still others, the wounded, the shocked, and the confused, became prisoners.

A member of the 146th last saw Col. Jenkins in the woods on the west side of Saunders Field, “leaning for a moment on his sword wiping perspiration and blood from his face with his handkerchief. He had reached within a few feet of the enemy’s works, cheering his men by his presence and inspiring them by his wonderful courage.” It was the last time anyone recalled seeing Jenkins. He was probably killed and then buried in an unmarked grave on the battlefield.

(Library of Congress)

Amazingly, somehow, the 140th’s Col. Ryan survived the bedlam. Capt. Farley recalled meeting Ryan, Maj. Milo Starks and Capt. Patrick McMullen back on the east side of Saunders Field. “It was a wild meeting,” claimed Farley. “Overcome by our conflicting emotions of wrath, excitement and mortification, we all talked at once. ‘My God,’ said Ryan, ‘I’m the first colonel I ever knew who couldn’t tell where his regiment was.’”

Indeed, all three of the Zouave regiments had suffered. According to the Official Records, the 140th lost 23 killed, 118 wounded, and 114 captured or missing, making a total of 255 casualties, which was almost half of the regiment. The 146th endured 20 killed, 67 wounded, and 225 captured or missing, totaling 312 losses, approximately half the regiment. Along with Col. Jenkins, Maj. Henry Curran was also killed. Less hard hit was the 155th Pennsylvania with 7 killed, 42 wounded, and 6 captured or missing, amounting to 55 losses.

Compared to the day before, May 6 was relatively quiet for the Zouaves of Ayers’ brigade. They moved to the south side to the Orange Turnpike, and while some served as forward skirmishers, others supported a battle line without getting engaged. After engineers completed an earthwork line, the brigade occupied it until dark and then received orders to reposition several times during the night.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse

(Tim Talbott)

On May 7, the Army of the Potomac advanced south from the Wilderness toward Spotsylvania Court House via Brock Road. In advance of the Fifth Corps, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s cavalry battled Confederate horsemen, slowly pushing them back, attempting to clear the way for Warren’s infantry.

The morning of May 8 witnessed the Fifth Corps dislodge the Confederate cavalry at Todd’s Tavern. Pushing on south, with John C. Robinson’s division in the lead and Griffin’s division following, Warren encountered Confederate infantry under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson arrayed on the Spindle farm, furiously digging in. The Fifth Corps commander, thinking he was facing dismounted cavalry, believed the time was ripe to attack before the Confederates fully entrenched with artillery support. Robinson’s three brigades along with Brig. Gen. Joseph Barlett’s from Griffin’s division attacked with devastating results. Griffin’s other brigades went in next, including Ayers’.

The 140th New York’s Capt. Porter Farley recalled, “All I can say is that in two or three minutes Colonel Ryan called on the regiment to follow him, and he dashed ahead on horseback.” Following their leader, and still in a column of fours, “in just the same order we had been [marching] in upon the road,” they “rushed on in that mad, blind style till our colonel was shot off his horse, our major [Milo Starks] killed and our men entangled among other commands. . . .” In too much confusion, “we fell back badly handled . . . with a loss of two officers and six men killed and two officers and about forty-five men wounded.”

Col. Ryan, shot through the body, apparently told Lt. John Buckley, who had his leg broken by a bullet and fell near Ryan, that he (Ryan) thought he was mortally wounded. One soldier, Pvt. Morris Ritter, was killed attempting to get Col. Ryan off the field. A few hours after the fight, Corp. Edwin Tripp went on the battlefield and carried Buckley into Union lines. Maj. Starks was killed instantly with a bullet to the head. Another officer, Lt. Erastus Davis, received a wound to the neck but remained with his company until back within their lines.

May 8, 1864, at Spotsylvania.

(Find A Grave)

The 155th Pennsylvania suffered, too. Col. Alfred L. Pearson noted in his report that in “charging the enemy’s position [we] found them in too large force to push forward our column, and halted in a favorable position, and received orders to hold it, which we did.” Col. Pearson also reported that on May 8, his regiment lost 6 killed, 38 wounded, and 3 missing. Among those killed was Capt. E. E. Clapp, who had earlier received a 20-day furlough. Instead of heading home, Clapp chose to pocket it due to the recent constant fighting. He felt he needed to be with his company. Pvt. Samuel Hill, wounded in the head by a minie ball, fell unconscious. Refusing a recuperative furlough, Hill returned to his company within a week, which was still at Spotsylvania.

The next three days saw Ayers’ brigade “in rifle-pits and on picket duty, exposed to the enemy’s shell fire and sharpshooters.” On May 12, in conjunction with the Second, Sixth, and Ninth Corps attacks on the Muleshoe Salient, Ayers’ brigade and other Fifth Corps units (excepting the two New York Zouave regiments) attacked again at Laurel Hill to hold the Confederate troops there in place. That night, Ayers maneuvered to the left in support of the Second Corps. On the morning of May 13, they marched about a mile back to the right and entrenched. That night, the Fifth Corps received orders to march from their position on the far right around the Army of the Potomac to the far left. The movement took all night.

(Image from Under the Maltese Cross: Antietam to Appomattox, Campaigns of the 155th Pennsylvania Regiment, published 1910.)

Arriving in their new position, and with little to no rest from the previous night’s march, two regiments, the 140th New York Zouaves and the 91st Pennsylvania, were ordered to drive the 9th Virginia Cavalry off of Myer’s Hill, a commanding piece of high ground in the direction of Spotsylvania Court House. Led by Lt. Col. Elwell Otis of the 140th, the roughly 300 men attacked the Confederate horsemen there, driving them back. Some of the southerners briefly took shelter in the Myers house and outbuildings before retreating. Confederate dismounted cavalry reinforcements arrived and counterattacked, now sending Otis’s men looking for cover around the Myers house. With increased Federal artillery fire from below the hill and the timely arrival of Col. Emory Upton’s Sixth Corps brigade, the rebel cavalrymen withdrew to the Massaponax Church Road.

Ayers’ two regiments were relieved by Upton’s brigade and returned to their Fifth Corps comrades at the Beverly farm, while Upton’s men began to entrench the position. Unwilling to give up the key position so easily, Gen. Lee instructed Lt. Gen. Jubal Early to recapture Myers Hill. A Confederate attack in the late afternoon by two brigades from Maj. Gen. William Mahone’s division drove off Upton’s men and almost captured Gen. Meade, who had come to see the position.

Back in safe confines, Meade ordered two Sixth Corps divisions and Ayers’ brigade to recapture Myers Hill. Ayers’ brigade arrived first. The Confederates, seeing the approaching Federal columns, realizing they were outnumbered and seeing the now changed disposition of the two armies’ lines, abandoned the position.

The three Zouave regiments in Ayers’ brigade did not participate in any other attacks at Spotsylvania. Their assignments were mainly performing picket duty and manning the earthwork lines. Over their last six days at Spotsylvania, they continued to endure casualties, but they now came in ones and twos instead of dozens at a time. On the afternoon of May 20, they set their sights south again and headed first for Guiney Station, and then other battlefields beyond.

(Library of Congress)

Conclusion

(Image from Under the Maltese Cross: Antietam to Appomattox, Campaigns of the 155th Pennsylvania Regiment, published 1910)

The 140th and 146th New York, and 155th Pennsylvania continued to serve in the Fifth Corps through the remainder of the Overland Campaign, the long Petersburg Campaign, and the Appomattox Campaign. They fought at North Anna, Totopotomoy Creek, Cold Harbor, Petersburg’s First Offensive, Weldon Railroad (Globe Tavern), Peebles’ Farm, Hatcher’s Run, White Oak Road, Five Forks, and Appomattox.

The earliest of the three Zouave regiments to muster out was the 155th Pennsylvania on June 2, 1865. The 140th New York completed their service obligation the following day. The 146th New York remained in service until July 16, 1865.

Some Sources and Suggested Reading

Brian A. Bennett, ed. An Unvarnished Tale: The Public and Private Civil War Writings of Porter Farley, 140th N.Y.V.I. Triphammer Publishing, 2007.

Brian A. Bennett. Sons of Old Monroe: A Regimental History of Patrick O’Rorke’s 140th New York Volunteer Infantry. Morningside Books, 1992.

Mary Genevie Green Brainard. Campaigns of the 146th Regiment New York State Volunteers. Schroeder Publications, 2000.

Charles F. McKenna. Under the Maltese Cross: Antietam to Appomattox, Campaigns of the 155th Pennsylvania Regiment. The 155th Regimental Association, 1910.

Parting Shot

at Rochester, New York.

(Gayle Ollson Hale, Find A Grave)

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

Join our community! Sign up for our newsletter to receive exclusive updates, event information, and preservation news directly to your inbox.